New Jersey Turnpike II

Fritz Lang’s silent film masterpiece “Metropolis” depicted the city of the future as a mechanical beehive of flying conveyances and skyscraper bridges, a matrix of manic efficiency, running ever faster and faster.

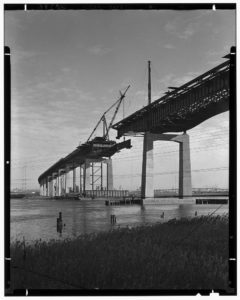

That was in 1926, and today’s cities have yet to approach Lang’s dystopian vision. Nevertheless, there is something familiar about it: the different kinds of vehicles, the multiple levels, the man-made environment, the relentless beat. … You could be describing the New Jersey Turnpike — at least its notorious northern stretch. Nowhere else in the world, it seems, can you find such a frenetic landscape, a 12-lane highway threading above and below other roads, beneath iron superstructures and electrical wires, past speeding jets and chugging freight trains, past cranes lifting tractor-trailer-size containers off seagoing ships, and over zigzagging pipes that emerge from a smoking, flame-waving oil refinery.

New Jersey owes its unfortunate national image to this one piece of road, which is many visitors’ most vivid visual and olfactory impression of the Garden State. It is also the basis of the infamous “what exit?” jokes -the title of an exhibit on the New Jersey Turnpike at the New Jersey State Museum.

The show was created by the New Jersey Historical Society as a half-century anniversary tribute to the turnpike and first shown at the society’s headquarters in Newark. Seeing it in Trenton, however, affords you the opportunity of a firsthand experience of the show’s subject, before and after seeing the exhibit. Going down, for example, I took for granted the straightness and flatness of the turnpike, not realizing that curves and grades were perceived driving hazards that engineers of the Fifties strove scrupulously to diminish or avoid. Nor did I realize that the bulk of the turnpike construction — including land acquisition — was completed in a mere two years, an unthinkable accomplishment today, where road mending projects seem to go on for decades.

The show is a surprisingly lively social history with lots of memorabilia and hands-on displays for kids, including a stretch of dented guard rail, a Howard Johnson’s restaurant booth, and a tollbooth complete with collector’s uniform for trying on.

The most unexpected revelation — given the turnpike’s gritty reputation today — is the utopian impulse behind its creation, as evidenced in several promotional films of the early Fifties, which sought to introduce people to a whole new concept in road travel. After scenes of traffic jams on Route 1-type roads, we see motorists zooming the spacious turnpike, “a new world” where service areas were staffed by uniformed male attendants who not only cleaned windshields and polished headlights, but performed “three-minute oil changes” and checked for mechanical problems. Women attendants, dressed like airline stewardesses, dispensed maps and travel information. In one cautionary tale, a cynical motorist fails to heed the advice of the mechanic-attendant to replace a fan belt and finds himself stranded with his family by the side of the road. Not to worry, however. The turnpike, forgiving as well as omniscient, is patrolled by service trucks equipped with a selection of fan belts and other emergency equipment. In no time, the converted cynic is back on his way, his wife and children happy and smiling.

Films promoting the wondrous road were not confined to the naïve Fifties, however. One from the early Seventies, titled “Incredible Journey,” trumpets the widening of the 30-mile northern section, with its four three-lane roadways known in turnpike lingo as a “dual/dual.” Another film, from 1994, celebrates the high-tech features that make the turnpike “one of the smartest roads in the country.” These include 1,000 traffic flow sensors and 73 electronic signs to advise motorists of what’s ahead.

The exhibit casts a wide net over its subject. It traces the history of pre-automobile toll roads, which go back to the late 1700s in this country. At that time, a sign tells you, a wagon with horse was charged 6 cents, while calves, sheep, and swine were a half-cent a head. The engineering accomplishments of the turnpike are cited along with contemporary accounts of its human costs. Predatory real estate agents, hired by the Turnpike Authority to acquire land, used scare tactics to make people sell at prices even lower than the appraised values. The biggest fight took place, not surprisingly, in the city of Elizabeth, cut in half by the turnpike’s construction. The drowning of two young boys in a construction pit further galvanized opposition, and in 1951, the Elizabeth police blockaded the city to keep out trucks and heavy equipment that city officials had complained were causing damage to roads and buildings.

In its early days, the turnpike had a high number of pedestrian fatalities as people – still unaccustomed to the inviolable nature of a superhighway — tried frequently to cross on foot.

The exhibit traces the evolution of public opinion toward the great roadway, from the wide-eyed wonder of the early days, through the dim view taken by environmentalists in the Seventies, and the criticisms by newspaper editorial writers of excessively high executive salaries and other perceived abuses of the semiautonomous Turnpike Authority.

Most interesting perhaps is the contemporary view, part of a willingness by New Jerseyans to embrace the grittier aspects of their identity, as evidenced by the pride in “The Sopranos” television show or the existence of a Weird New Jersey magazine. Instead of referring to the turnpike’s industrial scenery as “ugly,” people now describe it as “awesome.” Artists paint the turnpike, just as previous artists once painted the sublime spectacle of Niagara Falls.

The turnpike doesn’t participate in any of this. Its aesthetic position has remained pretty much unchanged for a half-century: It takes no responsibility for the scenery around the road. Spokesmen have said repeatedly that the authority plotted the safest, most efficient route. They point out that the road itself — regardless of landfill mesas or adjacent junkyards — is uniformly spotless. Nor does the Turnpike Authority care that a contemporary photographer might want to capture turnpike sights out of admiration rather than dismay. The rules remain the same: No one is allowed to stop and take pictures. Period.

This, after all, is not some quirky Route 66, which seems to throw up a museum to itself every few hundred miles. This is the New Jersey Turnpike, filled with seriousness of purpose. And that deserves some respect, grudging or otherwise.

New Jersey State Museum, Trenton

2003