Compared with the rest of the world, Mexico in the 1930s and 1940s must have looked pretty good. Fascism and Communist totalitarianism were sweeping through Europe and Asia. The United States was making the transition from a devastating depression to a wartime economy.

Mexico, though not immune to these global events, was in a golden age.

1945 portrait of Jacques Gelman by Angel Zarraga.

At the center of this Mexican Renaissance were the Mexican muralists, who celebrated a new national pride and the promise of a socialist workers’ paradise. And, at the center of the Mexican muralists was Diego Rivera, an artist of incredible vitality and creative power. With him was his artist wife, Frida Kahlo, not yet the cult figure she was to become after her death, but a woman of obvious feminine charisma.

It was “La Boheme” with palm trees and government subsidies. Everyone knew everyone else. There were European artists and intellectuals, Mexican movie stars, journalists, revolutionaries. The English-born surrealist painter Leonora Carrington moved there in 1942. When Leon Trotsky fled there from Stalin’s henchmen, he stayed with Diego and Frida.

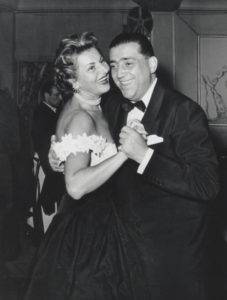

There were entrepreneurs, too. Despite the revolutionary rhetoric, you could still make a buck in Mexico. And one who did was Jacques Gelman, a Russian-born film distributor. He set up a Mexican company and made a fortune representing the popular Mexican comic actor Mario Moreno, known as Cantinflas. His wife, Natasha, immersed herself in the art scene. Together the couple filled that essential function in artistic flowerings – the patrons. If it wasn’t painted on a wall, there was a good chance the Gelmans would buy it.

Jacques and Natasha Gelman dancing in Mexico City.

Kahlo died in 1955, Rivera in 1957, but the Gelmans lived on in Mexico, continuing to acquire art (both European and Mexican) until Natasha’s death in 1998. An exhibit featuring the best of the couple’s collection has been touring the country and opens Sunday at El Museo Del Barrio in Manhattan.

Not surprisingly, Rivera and Kahlo dominate the show, but there are works here by David Alfaro Siqueros, Jose Clemente Orozco, Rufino Tamayo, Carrington, the caricaturist Miguel Covarrubias, and others.

Portraits are the dominant genre, and the personalities often emerge as more important than the art. In a shamelessly flattering 1945 portrait by Angel Zarraga, Jacques looks every inch a Forties mogul, suave in his double-breasted jacket and ascot, legs crossed in his folding director’s chair, cigar in hand, klieg lights being adjusted in the background.

Natasha is the subject of a half-dozen portraits by various artists. All tended to exaggerate her beauty and allure, though none more than Rivera, who made her look as glamorous as a movie star. She reclines on a couch, her white dress arranged around her legs so as to echo the form of the calla lilies behind her.

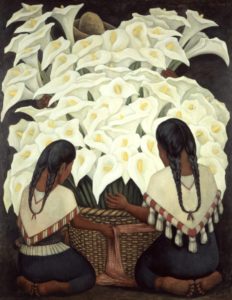

“Calla Lily Vendor,” by Diego Rivera from 1943.

Those white flowers with the prominent yellow stamens were a favorite motif of Rivera’s, and he used them to express both sensuousness and spirituality. In his “Calla Lily Vendor” of 1943, he depicts two kneeling, barefoot peasant women embracing a basket of flowers so huge and wondrous, it obscures all but the hat and hand of the vendor.

While Rivera painted the heroic struggle of a people, Kahlo looked inward and depicted her own struggles. Her life story was a series of catastrophes. Partially crippled by polio as a child, she barely survived a terrible bus accident at age 18 which impaled her on a handrail. She suffered with those injuries all her life, unable to complete a pregnancy and losing a leg in her later years. She referred to Rivera, whom she married at 22, as the second of her two “grave accidents.” His infidelities included an affair with her younger sister. They were divorced but remarried, and stayed so until she died at 47.

When surrealism’s founder Andre Breton came to Mexico and saw Kahlo’s paintings, he likened them to “a ribbon around a bomb.” When you know her story, the paintings make more sense, the resolute expression conveying her heroic pride and endurance. She expressed her heartbreak over not being able to have a child in “Self-portrait With Monkeys,” and in another portrait in which a lifeless doll sits next to her on the bed.

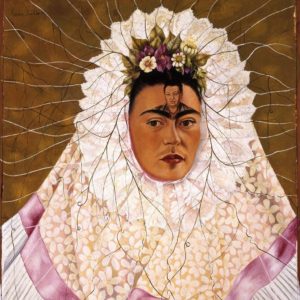

Kahlo’s “Diego on My Mind.”

But her paintings became progressively more bizarre, even by surrealist standards. Her indelible attachment to Rivera is graphically evident in “Diego on My Mind,” in which the image of Rivera’s face appears on her forehead, like a third eye. In the most outlandish of these pictures, she depicts herself, Madonna-like, holding a naked Rivera on her lap, flames erupting from his hand and blood from her chest. The two of them are embraced by a Mother Earth figure, in turn embraced by an even larger universe figure.

The other muralists, Siqueros and Orozco, don’t have a large presence, although there’s a strong self-portrait by Siqueros in dark, Rembrandtesque tones.

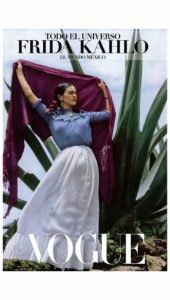

Kahlo on the cover of Vogue.

Rufino Tamayo, whose style combines pre-Columbian art with European modernism, emerges as an important talent here. His industrial scene of smoking factories has something of American precisionism in it, and his portrait of the comedian Cantinflas captures the actor’s demonic impishness.

Another interesting artist is Gunther Gerzso, who is still alive, a stage and set designer whose paintings have a delicate cubist structure.

There are all sorts of surprises here. The Rivera painting of the lascivious cactuses. The sexy photograph of Kahlo from Vogue magazine, which made a brief fad of her Mexican style of dress. The caricature of a blimpish Rivera by Covarrubias.

The Kahlo portraits will be a big draw of the show, but what the exhibit does best is to evoke the magical feeling of a special time and place, an intoxicating mix of glamour, intellectual idealism, creative intensity, and operatic tragedy.

El Museo del Barrio

2002