Not too long ago, you could rely on the International Center of Photography Midtown to stay focused on the craft of photography. ICP, after all, was founded by Cornell Capa, brother of legendary war photographer Robert Capa, and himself a noted portrait and documentary photographer.

But times change, and today ICP – once so square and earnest – looks more like an outpost of the Whitney Museum. Apparently, someone decided that ICP needed to get more edgy. It needed art that could rile Mayor Rudy Giuliani. It needed catalogs filled with references to “gender,” “identity,” and “sexuality.”

Photography could play an incidental role.

There’s no other way to explain exhibits that so perfectly conform to the contemporary art world cliches. “Behind Closed Doors: The Art of Hans Bellmer” deals with erotic, life-size female dolls (sexuality). “Kiki Smith: Telling Tales” is a feminist exploration of fairy tales (identity). And “Dear Friends: American Photographs of Men Together, 1840-1918” is about Victorian-era attitudes about homosexuality (gender).

Taken together, the shows exude a hothouse atmosphere of forbidden desires, Freudian repression, and adolescent fantasies. And, well, what else are museums for?

The Bellmer show is by far the most substantial and interesting. Bellmer (1902-1975) was a talented painter and graphic designer in 1920s Germany. After the Nazi rise to power in 1933, he turned to making provocative photographs of dolls. These big dolls, of his own construction, were disturbing combinations of childlike and mature female characteristics. They wear Mary Jane shoes and little white socks and have no pubic hair, but are shapely and full-breasted.

In one typical photo, the doll is posed provocatively, her chemise lifted up over her rear, her face turned to look over her shoulder with an expression that is part seductress, part victim. In this and some of the other photos, parts of the doll’s body are crumbling or missing, exposing armature and sockets.

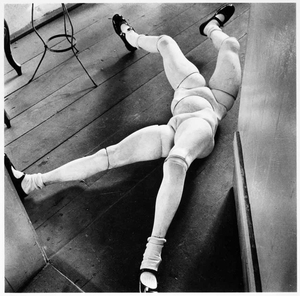

Others are grotesque reassemblies in which the body lacks head or arms but instead sprouts a second pair of hips and legs where the upper body should be. In others, the dolls’ ball-joint construction seems to run amok, like mechanical cancer, giving rise to conjoined spheres that suggest multiple breasts or buttocks or some other deformity.

Bellmer’s ability to merge such opposites as the erotic and the grotesque is what made him such a hit with the French surrealists, who eagerly published his doll (“La Poupee”) photographs in their journals.

The show argues for a political interpretation of Bellmer’s work – he was flaunting “degeneracy” in the face of Nazi repression – but it’s just as clear that the images touched some personal chord. It wouldn’t be art otherwise.

Memorabilia documents his period’s fascination with artificial females – from the Olympian doll of Offenbach’s opera “Tales of Hoffman” to the comely robot of Fritz Lang’s “Metropolis” to the stuffed companion that Austrian expressionist Oskar Kokoschka took out on dates. Other material includes books on sexual deviation in velvet-lined cases, naughty postcards, and Bellmer’s own erotic drawings in which transparent bodies take pornography to a new level.

Bellmer’s a tough act to follow, especially for someone like Kiki Smith, who plays in almost the same league. Like Bellmer, Smith makes fetishistic figures, but her work lacks that fundamental discovery, that core image that Bellmer built on. She investigates fairy tales and mythology, drawing heavily on Bruno Bettelheim’s “The Uses of Enchantment,” with riffs on “Little Red Riding Hood,” “Sleeping Beauty,” and Eve and the serpent.

She strives for shocking effects – Riding Hood with a hairy, wolfish face, and figures that, like Bellmer’s, span childishness and sexual maturity. But she obsessively scatters her energies across too many media: sculpture, installation, photographic sequences, videos, sound effects, music, drawings. The result is like an elaborate show-and-tell for a feminist tract.

The third, and smallest exhibit, is a quirky bit of social history, 75 daguerreotypes and other early photographic images of men – mostly twosomes – in affectionate poses.

The men certainly give the impression of being lovers, rather than just pals. They entwine their arms around one another, sit on laps, and pose cheek to cheek. That such photography was apparently not uncommon in a period – the Victorian era – known for its narrow-mindedness is the exhibit’s central mystery.

The pictures themselves, which were found in flea markets and among other memorabilia, offer no clues as to how or why they came into existence. Almost all are anonymous (except for one of Walt Whitman and a friend).

Are they evidence of a previously undocumented liberal tolerance of gay unions in Victorian times?

According to curator David Deitcher, 19th century Americans frequented studio photographers the way we take snapshots today. Photographs of same-sex friends were commonplace with the Victorian propensity for sexually segregated schools, clubs, military units, and workplaces. And, gay men – or women – were apparently able to stretch this convention to create the kind of photographs shown in the exhibit.

Perhaps in time, ICP Midtown will become known as a cutting-edge institution, a hip voice in the art world. But some of us were quite happy with its old identity as a straightforward venue for good photography. Right now, it’s wearing its ideology a little awkwardly, like a Midwesterner who has just arrived in Manhattan with an all-black wardrobe.

International Center of Photography, NYC

2001