When Walker Evans began taking photographs in the late 1920s, America’s most famous photographers were Edward Steichen and Alfred Steiglitz, both masters of a highly polished and poetic style, a photography of mist and soft edges that seemed to mimic painting.

Evans, a frustrated writer who admired the lean, plain prose of Ernest Hemingway, resolved to go another way. “I felt angry, and anxious to go in the opposite direction of these two men.” He set out to create a style that shunned artifice and allowed his subject to reveal itself directly and simply.

Now some 175 vintage prints are on display in the Metropolitan Museum’s “Walker Evans,” the first comprehensive retrospective of the photographer. It includes work from every period of his career, beginning with his earliest street scenes, taken in New York City and Italy in the late 1920s and early 1930s, and ending with Polaroids he took near the end of his life in the 1970s.

Evans once said of his work that he considered anything fair game for his camera “as long as it was man-made.” He wasn’t interested in nature or the abstract beauty of the human body. His landscapes were layered with human activity. Like an archaeologist probing a dig, he gathered as much evidence as possible into each photograph: papers strewn on the street, reflections in windows, signs, street furniture, telephone poles.

Evans showed us that anything could be art, that the most mundane objects, the most seemingly insignificant people had poetry and meaning.

His human subjects were as plain, as ordinary as he could find them; dockworkers, subway riders, and, of course, his most famous subjects: the Alabama sharecroppers of the book he did with writer James Agee, “Let Us Now Praise Famous Men.”

His celebration of the ordinary required a plain style, too. He perfected a style that has come to be seen as artfully neutral and calculatedly dispassionate. It was as far from what he called the “overstatement” of Steiglitz and Steichen as he could get.

The project with Agee had started out as an essay for Fortune magazine about tenant farmers. Although Fortune ultimately rejected Agee’s long text about three families of Hale County, he and Evans developed it into a 500-page book. When it was finally published in 1941, it sold only 600 copies and went out of print. It was reissued in 1960 to an enthusiastic new generation of Americans in search of a national identity.

Agee’s text – hyperbolic Whitmanesque prose alternating with tracts about farming – has not stood up as well as Evans’ pictures. In one portrait, a farmer rests in the doorway of a simple shack while his barefoot daughter sits gracefully on a chair, hands folded in her lap. Both look directly at the camera without a trace of self-consciousness.

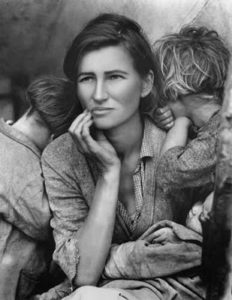

His portrait of Allie Mae Burroughs, the “Alabama Tenant Farmer Wife,” has been called a Depression Madonna or Mona Lisa, because of the ambiguity of its expression, a tight-lipped set of the mouth that somehow straddles grimace and brave smile. Critic Lionel Trilling called it “one of the finest objects of any art of our time.”

Some criticized Evans for not being a true documentarian because pictures such as this one were posed, not candid. Evans did his share of candid work – at one point hiding his camera in his shirt to snap subway riders sitting right across from him – but he also recognized that a person who is aware of being photographed reveals no less of himself, and often more.

He trusted his camera to capture the person by carefully recording every detail that presented itself to the eyes. By keeping his spaces shallow Evans was able to keep everything in sharp focus – the swirl of grain in a floorboard, the tattered fringe of old work jeans, the stubble on a chin. In his portrait of sharecropper Bud Fields, you can see the scab of a skin cancer on his lip and you can see, by the way his hair is damp and flat on the top of his head, that he has taken his hat off for the picture.

These pictures exposed an American tragedy, the terrible exploitation of a class of people who refused to surrender their dignity, but they also revel in the nobility of facts. He could bring that same passion for detail into a picture of an Alabama contractor’s storefront. The cheap metal building with the pile of dirt out front, is about as bleak and unpromising as a subject could be, but Evans’ composition, with its subtle shades of gray, makes the texture of the corrugated metal look as elegant as a pin-striped suit.

Although these scenes are not devoid of some social content – Evans never quite stopped being a writer – they are more striking because of the dignity they instill in ordinary reality. It’s right there in front of your eyes, Evans seems to tell us. You just have to look.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

2000