No one really knows what ancient Greek painting looked like. According to the writers of the time, painting was one of the supreme accomplishments of that culture. But, while Greek sculpture and pottery survived, the paintings crumbled away with the wooden panels on which they were painted.

The closest thing we have are first century Roman wall paintings, such as those excavated from Pompeii, and several hundred Egyptian “mummy portraits.” These latter were painted by Greek or Roman artists during the period of Roman rule, mostly in the first and second centuries. Though painted on wood, they have survived to this day just as the mummies did – because of the protection of the outer coffin and the dry Egyptian climate.

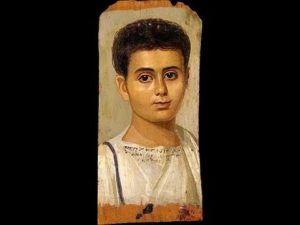

What’s most striking about these pictures is their naturalism. Unlike Egyptian art of the previous 2,500 years, which is heavily stylized, these pictures are realistic, executed in the Greek tradition of three-quarter view, with a single light source casting shadows and highlights on the face.

Perhaps because of their hybrid origins – neither purely Greek nor purely Egyptian – they occupy an odd corner in art history.

Now about 70 of these rare and fragile works are on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in a show titled “Ancient Faces: Mummy Portraits From Roman Egypt.” Ancient or classical art may impress us with its beauty, but we rarely feel close to it. Not so, here. These people seem warm, alive, and even familiar. They look straight out at us with large, moist eyes and frank expressions.

There is nothing false, no apparent attempts to flatter, as there is in so much portraiture. Perhaps this is because the subjects were dead when the paintings were made, but, in fact, no one knows if that’s true. Because so many of them are young, in the prime of life, it has been suggested that they were done years before the subjects’ death, and perhaps hung in the home before being used for funereal purposes. But recent CAT scans of the mummies reveal that the people inside the wrappings were about the same age at death as the faces in the portraits appear, suggesting that they were done posthumously.

If so, the artists who painted them were quite gifted at creating the appearance of a life portrait, giving the faces specific expressions and the kind of presence that seems far removed from a corpse.

Many of the mummies come from an oasis west of the Nile valley known as the Fayum, so many in fact, that they were once called Fayum portraits.

The painted panels were part of the inner layer of coverings in the mummification process, put directly over the face and held in place by the linen wrappings. Seen in that context, they look oddly out of place, both because of the painting style (we expect one of those rigidly symmetrical Egyptian faces, more an idealization than likeness) and because the people are dressed and adorned like Romans. Roman styles of dress, hairstyles, and jewelry were in vogue all across the empire.

However, although they may have adopted Roman ways, and although many of these people may have been of mixed ethnicities (Roman Egypt was a truly multicultural society), they clearly retained traditional Egyptian religious beliefs about the afterlife, or at least felt connected to Egyptian traditions. The most vivid of these portraits were done in encaustic, a beeswax-based medium that resists drying, fading, and cracking. At the same time, the waxy paint retains the brush strokes, and gives these works a directness and painterliness that looks almost modern.

However, although they may have adopted Roman ways, and although many of these people may have been of mixed ethnicities (Roman Egypt was a truly multicultural society), they clearly retained traditional Egyptian religious beliefs about the afterlife, or at least felt connected to Egyptian traditions. The most vivid of these portraits were done in encaustic, a beeswax-based medium that resists drying, fading, and cracking. At the same time, the waxy paint retains the brush strokes, and gives these works a directness and painterliness that looks almost modern.

Unlike the idealizations of the deceased that characterize ancient Egyptian burial portraits, those of the Roman period are highly particular. The artists didn’t flinch at including flaws or oddities such as wrinkles, bags under the eyes, asymmetries, or double chins. We see the wispy beginnings of beards and moustaches on young men, a mole on the side of a man’s nose, even a surgical scar under a boy’s eye. A woman has ears as pointy as a fox’s, and almost every face has large, dark soulful eyes, some rimmed with black eyeliner. A man, apparently an athlete, appears shirtless, allowing us to see his arched deltoid muscles.

Posthumous portraits often betray a funereal feel – something creeps into the expression – but the people in these pictures are so vital and engaging that it’s easy to forget the picture’s function. A cherubic boy gazes out at us with the same kind of innocence and promise that we might see today in a Communion or bar mitzvah picture. The women sport a variety of hairdos, from those with a profusion of ringlets and curls to ones pulled severely back.

So much is unknown about these pictures. We don’t know the names of the subjects or the artists. We don’t know how the subjects died, or much about how they lived beyond the clues found in dress or jewelry. And yet, despite a gap of 2,000 years, they are as real to us as the faces in the daily newspaper.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

2000