It’s one of the most famous images in American photography: a dark, rainy street scene with an odd V-shaped building looming large against the twilight sky.

The building is The Flatiron, and the 1904 photograph, by the same name, is by Edward Steichen. Like all of his early photographs, it is moody and mysterious, all inky shadows, blurry street lights, and reflections off rain-slicked pavement.

But, the more you look, the more subtle effects you discover: the way the lines of buildings converge at the top-hatted figure in the foreground. Or, the way the Flatiron building runs off the picture, flattening it into a stronger two-dimensional shape. It is as carefully composed, in fact, as a painting – no easy feat for a photographer – but then again, Steichen was a painter, too.

That’s only one of the surprises of the Whitney Museum’s current exhibit, which has about 200 vintage prints and several paintings and shows this 20th century photographer to be a much more complex figure than I, for one, had thought. It’s not so much that he painted, too; others have done that – Man Ray, for one. But over the course of about a half-century, Steichen seemed to reinvent himself every decade or so, adopting a style or philosophy of photography that might have seemed irritatingly contradictory in a lesser artist.

He’s often confused with photographer Alfred Stieglitz, husband of Georgia O’Keeffe, and about 15 years Steichen’s senior. The two had an important association for several decades, centering on a group called the Photo-Secession, which was committed to establishing photography as fine art. Together, the two started the 291 Gallery on Fifth Avenue. Steichen spent a lot of time in Europe, where he championed the modernist work of Brancusi, Cezanne, and Rodin and helped make the 291 Gallery a showcase for avant-garde art.

Steichen started out as a proponent of the pictorialist style, which employed moody, atmospheric effects like those of “The Flatiron” and owed much to tonalist painting and the near-abstract “nocturnes” of James Whistler. Steichen’s oil paintings – phosphorescent trees that seem to billow up like smoke clouds against the midnight blue sky – look too saccharine, too fanciful next to the photos. The photos are dreamlike, too, but rooted in reality, and are much more convincing.

But mainstream photography at the time favored the sharply focused and literal, and there was open hostility to the eerie, moonlit groves and heavily shadowed, dreamy nudes of the pictorialists.

To achieve these effects, Steichen sometimes shot through colored lenses or sprinkled water on his lens to blur the image. Other times, he used a gum process that allowed him to manipulate the print with a brush or scraping tool. The resulting chiaroscuro and painterly brushstrokes lent his photographs the appearance of drawings or lithographs, causing one critic to dub them “paintographs.”

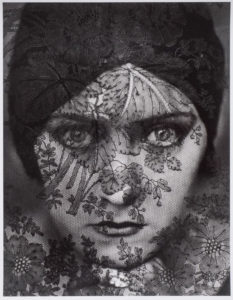

Actress Gloria Swanson

But Steichen continued to experiment, trying out three-color prints and montaging negatives to create combined images, such as one that juxtaposed the meditative profile of his friend Rodin with his famous sculpture, “The Thinker,” and a marble statue of a white-bearded man.

In response to photographic purists who said that Steichen’s innovations violated the integrity of the medium, Steichen argued that all photographs were “faked” because of camera mechanics and printing techniques. But many photographic competitions began excluding manipulated photos on the grounds that they were not photographs.

Steichen, however, had apparently already grown tired of pictorialism’s limited range of moods and expression, and, in the years before and after World War I, seemed to join the opposition, with subtle and sharply focused studies of still-life subjects, including close-up images of fruits and vegetables, such as one of a split avocado.

Steichen also continued to paint. On view is one of the seven mural panels he made for the foyer of a rich couple’s Park Avenue town house, a series that he worked on for four years. The 10-foot-tall panels were dominated by images of flowers and diaphanously draped female figures, and painted in a highly stylized, luminous style, employing gold leaf and bright colors, a style that looks like a combination of pre-Raphaelite art, Gustav Klimt, and art deco.

Steichen donned a new persona in the 1920s, returning to New York from Europe to become chief photographer at Conde Nast publications. From 1923 to 1938, he photographed celebrities each month for Vanity Fair and did fashion photographs for Vogue. He became America’s court portraitist.

As a commercial photographer, he wasn’t charged with looking behind the facade of his celebrity subjects, but to enhance, and to further glamorize, their public personas.

Actress Gloria Swanson, for example, stares out at us from behind a patterned lace veil, her heavily made-up eyes so intensely feline that she looks supernatural. The ultra-sophisticated Noel Coward stands aloof – the omniscient playwright – his face crisscrossed with light and shadow, the trademark cigarette sending up a lazy trail of smoke. Marlene Dietrich is seen asleep in a wing chair, her face emerging from the nest of a black ruffled collar or boa, as if offering up its perfection. The young Gary Cooper is bursting with vitality and good looks.

In his advertising work, he created scenes, such as those for Kodak, which showed idealized slices of middle-class American life. During this period, Steichen – perhaps somewhat defensively – insisted that there was no difference between fine and commercial art. This, of course, angered the fine artists who felt that what they did represented a search for something higher.

As abruptly as he had taken it up, Steichen quit commercial photography in 1938. In the last phase of his career, Steichen embraced the documentary approach to photography. Instead of photographs as poetry or celebrations of fashion, he saw photography as a tool for mass communication. He became curator of photography at the Museum of Modern Art and organized the famous “Family of Man” exhibit of 1955, considered by many to be the greatest photographic exhibit of all time. Steichen collected 503 photographs from around the world and organized them according to universal themes, such as marriage, childhood, work, and religion, in a modernist, montage-like display that is evoked in the Whitney show.

The last section of the exhibit is devoted to Steichen’s final years (he died in 1973 at age 94), when he worked with color film and focused on a single subject – a shadblow tree that he could see from the window of his Connecticut home. Although the style is nothing like his early pictorialist phase, there is something in the meditative attitude and focus on nature that suggests a life come full circle.

Whitney Museum of American Art

2000