Repetition is the addictive obsession of the artists from the 60s and 70s, at least the ones who ushered in styles like pop, minimalism, conceptualism, photorealism, and post-minimalism.

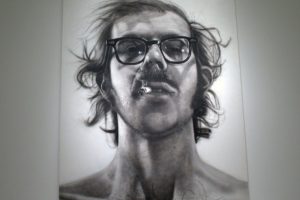

“Big Self Portrait” by Chuck Close

The theories behind all of these isms (why, one wonders, was pop never popism?) were intricate and florid, whereas the art was simple, deadpan, and unbelievably repetitive. Warhol stamped out his soup cans and his multiples of Marilyn, minimalists like Richard Serra made us to stare at sheets of lead, Donald Judd gave us plywood boxes, and the photorealists gave us pictures that looked like they’d just floated up out of the developing fluid.

Among these artists is Chuck Close, who, like many of his generation, began as an abstract expressionist, then rebelled against it. His obsession was to make giant photorealist portraits of himself and his friends. The name has always seemed a put-on (though it isn’t), because these images do nothing so much as bring us up close to the subject, often closer than we really want to be.

Close’s career, the subject of a big retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, is fascinating for its dogged persistence, demonstrating how an artist can lock himself into a rigid system, and then struggle – like a magician in a trunk – to set himself free.

Close’s bondage of choice is the grid, a graph-paper matrix upon which all his paintings are organized. In subject, he has shackled himself to the frontal portrait, and in style, to the kind of image rendered by the camera.

So what you see at the Chuck Close show is room after room of monumental heads, devoid of any of the emotion or expressiveness that one associates with portraits, and constructed, inch by inch, out of little squares. His sole maneuvering room is, as it would have to be, within the confines of the tiny squares. Where Close wiggles a little free is in the use of different media – acrylic, watercolor, oils, paper pulp – and in the kind of mark he puts within each box – impressionist color, pointillist dot, or decorative squiggles.

Like his contemporary the late Roy Lichtenstein, Close is overly fascinated with the Benday dot illusion. Blow up any magazine photograph big enough, and it turns into a meaningless pattern. Step far enough away from it, and the image pops back into its familiar form. This is a perceptual game, and not a new one. Impressionism relied on the same ability of the eye to resolve and organize disparate strokes of color into a unified image.

So, although it is amusing to see Close push the limits of the Benday dot by running wild within the little squares, it’s not enough to carry the show. No, Close’s career turns out to be one about process, about these very issues of freedom and limitations, of system vs. improvisation, of being maddingly repetitious – like minimalist music – and then injecting tiny variations.

Close’s most famous picture is still the first gridded portrait he made and the one we see at the outset of the show: “Big Self-Portrait” (1967-68).

It’s a funny picture, because of its obnoxious, in-your-face attitude. The artist, a long-haired, stubble-chinned counter-culture icon, thrusts his jaw out defiantly, a smoking cigarette between his lips. The photograph from which it was copied is also on display, with the superimposed grid that he used to transfer the image to the larger canvas.

In these early paintings, the grid is often buried beneath the paint strokes, but in subsequent works it emerges as an acknowledged device, a part of the composition. The subjects of the other paintings from this early, monochromatic mug-shot group are Close’s friends: the artists Richard Serra and Nancy Graves, the composer Philip Glass. (He has refused throughout his career to do commissioned portraits.)

As portraits, they are ugly and unflattering. Close delights in the discovery of imperfections through enlargement. We are confronted with the asymmetries of noses and nostrils, the cracks of the lips, the hairs that seem to sprout everywhere. These first pictures, too, slavishly imitate the camera, showing in sharp focus that which is near, and softening that which is at a distance.

He subsequently abandoned this grotesque detail, lost what small interest he had in his subjects, and turned himself wholly over to system.

In one series, he begins with a small portrait of a man’s head and begins to blow it up, naming each picture for the greater number of squares in the grid from 154, to 616, to 2,464, and on up to the monumental one, with 104,072 squares.

Instead of a portrait, we are encouraged to think in terms of information bits. How many strokes, how many millions of modulations, go into each one? For, despite their mechanical appearance, they are painstakingly painted by hand. His method, in fact, is so time-consuming that the artist has made only about 70 paintings in his career.

From this point forward, the grid becomes an increasingly important image, while the methods used to patch together the images stretch across almost every painting medium, including a technique in which the paint is applied by fingertip. Some use a buildup of nested dots that remind us of Van Gogh or Seurat, others a tapestry-like weaving of gestural strokes. Some of the latest paintings have a kaleidoscopic, vibratory appearance. One, of the painter Lucas Samaras, an artist known for his mystical intensity, looks like a carnival spin-art painting, with the face seeming to radiate energy like a sun.

In 1988, Close became partially paralyzed as a result of a burst blood vessel in his spinal cord. His rehabilitation is something of a legend in the art world, and the artist, working from a wheelchair, was able to resume painting, using lifting equipment to raise and lower himself in front of his monumental-sized canvases.

In the pictures from the late Nineties, the image becomes increasingly abstract. The grid boxes are filled with tiny designs – blips, bull’s-eyes, squares within squares, and even figure-eight forms that spread across two boxes – each like a miniature abstract painting, as if the artist were recalling his early roots.

With these, the surface commands such interest that there’s less temptation for the viewer to step back for the big image.

Close’s career is a strange, obsessive journey, What you take from this show is a sense of art as process, not as a finished object. This is an idea with built-in limitations — somewhat like the novelist who constantly interrupts his story to remind you that he is writing a novel. We may gain some small philosophic insight into the nature of art and the creative process, but will almost certainly come away feeling deprived of something fundamental.

Museum of Modern Art

1998