Self portrait

Edouard Vuillard is an easy painter to love. His intimate interiors are jigsaw puzzles in which all the elements – the faces, tabletops, curtains, rugs, windows and doorways – fit together into a gorgeous pattern. Like the cubists, he broke up reality and reassembled it, but unlike the cubists, the results were never jarring or sharp-edged.

He was the charming modernist. He is often paired with Pierre Bonnard, with whom he came of age artistically in the 1890s. For awhile their works were quite similar, but they branched apart around 1910. Vuillard’s work became more realistic and conventional. Bonnard stayed the modernist course.

Most exhibits and art books on Vuillard tend to shy away from the late work. But he lived till 1940 and that’s a lot of art to ignore.

In “Edouard Vuillard: A Painter and His Muses, 1890-1940,” the Jewish Museum takes a different tack. The emphasis here is on social history – Vuillard’s involvement with the avant-garde cultural milieu of Paris at the time, a scene in which Jewish collectors, gallerists, publishers and theater impresarios apparently played an important part.

Marcelle Aron

Vuillard was Catholic, but he belonged to a group in the 1890s called the Nabis (rhymes with hobbies) which included some Jewish artists and others, like Vuillard, who wore long beards. The group’s name comes from the Hebrew word for prophet or visionary.

In this exhibit, the five decades of Vuillard’s career are given equal weight, which gives a much fuller picture of Vuillard, the man. For example, Vuillard’s early work, which often features his mother and sisters with whom he lived, might give the impression that he was a mama’s boy. But women played a big part in his life.

In fact, he seems to have had a habit of getting involved with the wives of important benefactors. The first was Misia Natanson, who played the muse (and portrait subject), for a number of important artists, including Bonnard, Felix Vallotton and Pierre Renoir. Misia’s husband, Thadée, from a family of Polish-Jewish bankers, was a founder and publisher of the cutting-edge cultural journal, La Revue Blanche.

In one painting, Thadée can be seen at as his large wooden desk in a warm, lamp-lit interior. In another of the magazine offices, the critic Felix Feneon can be seen comically hunched over his desk, his nose practically touching the paper he writes on.

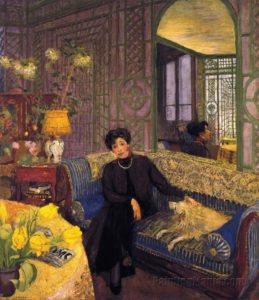

Lucie Hessel

The Natansons were Vuillard’s entry into society and helped to get him into the prestigious Bernheim-Jeune gallery. In another witty picture, you see the sharply dressed art dealers Gaston and Josse Bernheim, one of whom perches rakishly on the arm of a chair. By this time, the Natansons had divorced, and Vuillard was adopted by the third partner in the gallery, Jos Hessel and his wife Lucie.

Lucie became Vuillard’s adored confidante and lover. She appears in more pictures than any other subject, from the lyrical and slightly blurry “Madame Hessel at the Seashore” of 1904, in which she slumps dreamily next to a window, to the formal 1924 portrait in which she is gray haired and sits in a matronly pose in her painting-lined living room.

Vuillard by this time was up to his ears in the culture of wealth and privilege. The former Nabi and painter of stage sets and playbills for avant-garde theater, became a society portrait painter. The subjects of these paintings, you gather, didn’t want their faces blurred into the wallpaper as just another piece of the modernist pattern. The paintings still have Vuillard’s great color sense and love of rich, complex interiors, but they are no longer daringly flat, abstracted compositions. The entire last gallery is devoted to paintings he made at the Hessel’s chateau near Versailles. Everything came to end in 1940 with Vuillard’s death and the Nazi occupation of Paris, which brought a tragic end to a cultural milieu that had nurtured so much art, theater and literature.