More than 50 years after Jean Dubuffet coined the provocative term “art brut” – literally “raw art” – the audience for it couldn’t be less shocked. Back in the 1930s, when the French painter began touting the work of graffiti scrawlers, psychics, and the institutionalized insane, it must have seemed, to the average person, like one more outrage of modern art, another assault on the traditional ideals of beauty and harmony.

Dubuffet not only admired the art of the untutored and unbalanced, he tried to paint that way himself, with brutally distorted, primitivistic stick figures incised in coarse grounds of paint, sand, dirt, and glue.

Now, “outsider art,” as it is called today, has become so popular that it’s in danger of losing its outsider status. There’s a museum devoted to it in Baltimore, and names like Adolf Wolfli and Henry Darger are now known well beyond once-small circles of specialist scholars and collectors. This weekend marks the ninth annual Outsider Art Fair downtown in Manhattan, while uptown, the Museum of American Folk Art kicks off an exhibit of art brut.

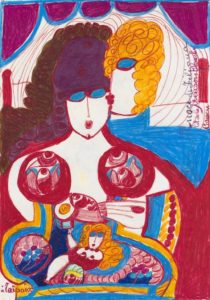

A painting by outsider artist Aloise Corbaz.

On view are about 100 works from the collection of the Paris-based foundation ABCD (Art Brut Connaissance & Diffusion), which is dedicated to promoting awareness of art brut, of which Dubuffet identified four strains: by asylum inmates, spiritual mediums, the isolated, and the self-taught. (Technically speaking, “outsider art” is a broader term than art brut, covering not only art by naive or disturbed artists, but that by trained artists who work in idiosyncratic styles – like Dubuffet.)

The exhibit is divided up along Dubuffet’s breakdown, with the biggest number of works coming from the ranks of the insane. To Dubuffet, art was art, regardless of who created it, and he resisted any attempts by critics or historians to marginalize art brut. But, to avoid the stigma of mental illness, he played down that aspect, and instead attributed the artists’ originality to their cultural innocence.

It was this search for art completely uncontaminated by culture that led Dubuffet into Europe’s asylums and psychiatric clinics. Among the artists whose work he collected were Wolfli and Aloise Corbaz.

Wolfli (1864-1930), a Swiss laborer and alleged child molester, spent the last 35 years of his life in a Bern clinic. In 1921, his psychiatrist, Dr. Walter Morganthaler, brought the world’s attention to his work with a paper titled “A Mental Patient as Artist.” Wolfli, obsessively prolific like many such artists, created a 25,000-page opus, combining musical compositions, poetry, and 3,000 illustrations.

“Christoph Columbus” is typical of his early work, a symmetrical composition – a mandala of sorts – with a stylized face in the center and mythical animals along the border. The work has a natural affinity with the totemic art of the Kwakiutl Indians of America’s Pacific Northwest – art that Wolfli almost certainly never saw.

Bold and sometimes compulsive patterning is a hallmark of art brut, and Wolfli’s art became progressively more so as he got older. Greeting visitors at the entrance to the galleries is his giant pencil drawing, put together from four sheets of paper and measuring about 6 feet across. Its dense, diagrammatic image is part map, part cityscape, part architectural drawing. Musical notation, script, abstract designs, and small decorative heads inhabit the meandering tracks and channels of this elaborate design. Streets and buildings pop up in one section, while another large form looks like some kind of vessel, a cutaway view of a submarine.

What stands out is the certainty and steadiness of the artist’s hand. Wolfli doesn’t hesitate, or rework. It’s hard to tell if this is because he has a complete conception of what he wants before he puts it down, or because he simply follows his instincts wherever they lead him, from one edge of the paper to the other.

Corbaz (1886-1964) was also Swiss, and had been a governess in the court of Kaiser Willhelm II of Germany before World War I. She began producing artwork shortly after being institutionalized in 1918, and by 1936, the doctors of La Rosiere asylum were collecting her drawings and paintings. If Wolfli’s work has a primitivistic flavor, Corbaz’s remind us of Matisse or the German expressionists. She created a perfumed and colorful world populated by kings, queens, dukes, and duchesses in a setting of courtly opulence – all of it dedicated to expressing her unrequited love for the kaiser.

Spiritualism was very big in the first half of the 20th century, and it apparently spawned enough examples of trance-induced “automatic writing” to warrant its own category. These mediums took no credit for their works, but claimed to be “channeling” creative forces. Madge Gill (1882-1961) had a spirit guide named Myrninnerest, who compelled her to begin drawing at the age of 37. Her pen-and-ink drawings feature the repetition of a woman’s face enmeshed in interlocking geometric patterns formed by one continuous, flowing line.

Those Dubuffet called “isolates,” or solitaries, produced their art in secret. Darger (1892-1973) is the best known American in this category. He was raised in a Catholic home for boys, and was institutionalized as a young man for behavior problems. He then settled into a routine as a janitor at a Catholic hospital. In his spare time, he worked on a massive illustrated saga called “The Story of the Vivian Girls in What Is Known as the Realms of the Unreal, of the Glandeco-Angelinnean War Storm, Caused by the Child-Slave Rebellion.”

The creepy illustrations are a psychiatrist’s field day, with gruesome battles between the evil Glandelians, who look like Nazis, and the little Vivian girls in their bows and frilly frocks, who look like figures copied from a child’s coloring book. The child-slaves have female features and penises. Although Darger’s work fascinates many, and is widely exhibited, his work is among the least interesting artistically. The figures really do look traced, and repeated in a rubber-stamp way, creating horizontal multifigured compositions that look like wallpaper – except for the grisly hangings and strangulations.

These are sick images. Darger’s appeal seems based less on the art than on the romantic myth of the isolated outsider artist who is only discovered after his death. It was Darger’s landlord who found his life’s work, which included the 12-volume, 15,000-page epic of the Vivian girls.

Dubuffet’s last category – self-taught artists – doesn’t quite fit the “raw art” category. The work of these more or less ordinary folk – clerks, housewives, shopkeepers – lacks the edge of the true outsider. The mysterious, almost elegant designs of Scottie Wilson, a Scottish-born Canadian who “doodled” in the back room of his secondhand shop for 37 years, are odd, yes, but fundamentally rational.

Which brings us back to Dubuffet’s insistence that it is naivete and indifference to artistic traditions that is art brut’s most salient feature. Such a description might fit a rural folk artist like Grandma Moses, but it ignores the irrational nature of art brut. The art of these schizophrenics, psychotics, spiritualists, and recluses isn’t one of childlike innocence, but one of strangeness, obsession, claustrophobia, and bizarre preoccupations.

And, this is precisely why we are drawn to it – because we are curious about this dark side of human nature, and because these people are unquestionably the real thing. For them, art wasn’t some pose or game. They didn’t have to strive or struggle to suggest a surreal world. They lived in a surreal world, and their art gives us a peek into it, and a taste of what it might be like to be them.

Museum of American Folk Art

2001