France invented high culture. America invented popular culture. The intersection of the two was one of the most interesting chapters ever written in the history of style. It happened in the 1920s and 1930s and was largely a tale of two cities, Paris and New York. If you had to sum it up with one name, it would probably be art deco, but that’s far from the whole story.

For the whole story – or close to it – go the Museum of the City of New York, where the exhibit, “Paris/New York: Design Fashion Culture 1925-1940,” charts this fascinating cross-fertilization as it played out in the fields of architecture, furniture, cuisine, music, art and graphic design.

The museum describes the relationship as a “love affair and rivalry” between two world capitals, in which New York ultimately emerged as the dominant partner and global trendsetter. Most of the action takes place at expositions, fairs and museum shows. The big ones were the 1925 Paris Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes (from which the terms art deco — an abbreviation of Arts Décoratifs — and art moderne were ultimately taken) and the 1939/40 World’s Fair in New York.

American designers snatched up ideas by the handful at the ’25 fair with the result that American department stores like Lord & Taylor’s started offering imitations, such as the two seen here: a knockoff of an elegant Emile-Jacques Ruhlmann table with plastic drawer pulls and a similar popularization of a Leon Jallot table – orginally covered in sharkskin, but offered to the masses in painted-wood.

This was not the kind of exchange the French had in mind. Here, as elsewhere in the exhibit, you’re reminded of the relationship today between America and China, with America now in the role of the established cultural power and China as the upstart imitator.

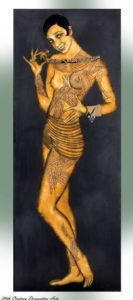

Not that America didn’t have things the French admired – its skyscrapers, for example, and its jazz, epitomized in Paris by dancer Josephine Baker, whom Parisians saw, according to catalog essayist Jody Blake, as “simultaneously the primordial Black Venus and the quintessential modern flapper.” A brief filmstrip captures Baker’s famous banana-skirted hip-shaking dance that morphs into a Charleston.

And what better symbol of the period than a life-size, cut-out lacquer figure of Baker by Jean Dunand and Jean Bamber-Rucki in which the dancer’s body is ornamented by zig-zag art deco patterns?

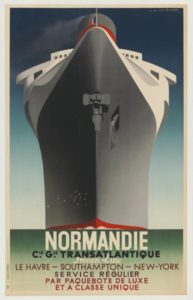

You can also see images and decorations from what was probably the most ostentatious display of French culture in that period: the ocean liner Normandie, a ship so tasteful, chic and elegant – it was promoted as “Paris afloat.” For half a decade, crossing the Atlantic in a mere four days, it brought French culture to the shores of Manhattan, as symbolized in a photo collage showing it parked in among New York skyscrapers.

Rockefeller Center brought together the best of the two cultures – the smart, setback style of the American skyscraper, with the detail and ornamentation of French designers.

The 1939/40 World’s Fair with its “World of Tomorrow” theme trumpeted America’s streamlined machine-age design to the rest of the world, a style that was being offered not just to rich consumers but to everyday people in the form of toasters, refrigerators and automobiles.

One thing the Americans never tried to imitate or popularize was French food, which was offered – in pure haute-cuisine form at the French Pavilion of the New York fair. This proved to be a significant foothold, as it resulted in the first real French restaurant in New York, Le Pavillon. Unfortunately the museum can’t provide the taste experience, but visitors can see photos, the original menu, and a fascinating “family tree,” by American food critic Craig Claiborne showing how so many of the city’s great restaurants, such as the Four Seasons and La Carvelle, were descended from it.

The show was organized by the Donald Albrecht, the museum’s curator of architecture and design who also edited the excellent catalog.