Asked how they like Bronzino, many people might say grilled. Today, the 16th-century artist Agnolo Bronzino is probably less well-known than the European sea bass served in restaurants. The Metropolitan Museum hopes to change that with “The Drawings of Bronzino,” an exhibit of some 60 works on paper that curators say is the first comprehensive exhibit of Bronzino’s work ever, anywhere.

Asked how they like Bronzino, many people might say grilled. Today, the 16th-century artist Agnolo Bronzino is probably less well-known than the European sea bass served in restaurants. The Metropolitan Museum hopes to change that with “The Drawings of Bronzino,” an exhibit of some 60 works on paper that curators say is the first comprehensive exhibit of Bronzino’s work ever, anywhere.

There are only two Bronzinos in New York City, both portraits of young aristocrats. One hangs in the Metropolitan, the other in the Frick and both have that slightly edgy and peculiar quality that you associate with mannerism. The handsome young man of the Metropolitan’s painting has eyes looking off in two different directions. His slack-faced contemporary (Lodovico Capponi) at the Frick is wearing one of those ridiculous codpieces that make a wearer look like he’s concealing a doorknob in his pants.

Well, apparently dandies of the 1500s sported such attire. You can hardly blame Bronzino for that.

One reason for the 350-year gap in this Old Master’s exhibition credits is that many of his works are wall paintings that can only be seen in his native Florence. But that can’t be the only reason, since there are enough easel paintings scattered around the United States and Europe to do a Bronzino show (and apparently one is now scheduled for the Palazzo Strozzi in Florence in September).

My guess is that it has something to do with the oddities of mannerism. People nowadays have a hard time understanding why artists of that period felt the need to bend and twist reality into something strange and artificial. The answer lies in what came before. Mannerism was an assertion of style over naturalism, a reaction to the balance and harmony of such High Renaissance artists as Raphael.

They thought they were fighting cliches. Viewed out of historical context, it can just look perverse.

Take Bronzino’s “allegorical portraits,” in which he painted his patrons as semi-nude mythological figures. In the catalog for this show, there’s a reproduction of his painting of Duke Cosimo I de’ Medici as the lyre-playing Orpheus. The Medici were the powerful bankers who financed the Renaissance. Imagine Warren Buffet’s head atop the replica of Michelangelo’s “David” at Caesar’s Palace in Atlantic City and you have a sense of how peculiar this looks.

Bronzino owes his mannerist tendencies to Jacopo da Pontormo, the eccentric master to whom he was apprenticed in his early teens. Early on, it’s difficult to tell the difference between the two. There are pages in this exhibit that have a Pontormo drawing on one side and a Bronzino on the other. The bringing together of all of Bronzino’s known drawings for the first time has been a thrill for scholars who are already resolving once fuzzy or mistaken points of chronology and attribution.

Compared to some mannerists, such as Hendrik Goltzius with his grotesquely muscled men and Parmagianino with his swan-necked women, Bronzino is mannerist-lite. And, in a show of his drawings, this toning down is even more pronounced. That’s because Bronzino didn’t draw to make finished works. These are all working drawings, done from models in preparation for paintings, not as ends in themselves. As such, they are truer to life.

A perfect example are two star images from this exhibit, an angelic face of a curly-haired child with hopeful upturned eyes and “Head of a Young Woman in three-quarter View,” with compassionate or demure downcast eyes, are as charming and as harmonious as any Renaissance drawing. Both of these images underwent subtle tweaking and nudging when transferred to canvas so that the same faces look slightly stranger in the finished paintings.

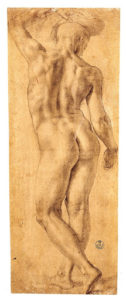

Mannerism’s tendency to twist the human figure can be seen in Bronzini’s standing male nude, a study for “The Crossing of the Red Sea,” with its exaggerated cock of the hips and arch of the back. The tendency to elongate can be seen in a drawing of a long-torsoed seated female nude.

Sometimes figures are slightly androgynous — feminized male physiques and masculine-looking female ones.

Although Bronzini is often referred to as a portrait painter, you won’t get that impression from this show, presumably because the portraits, done from life, didn’t require the kinds of preliminary drawings that the big multi-figure narrative works did.

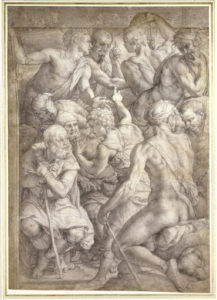

In those, as elsewhere, you’ll find more naturalism in the studies of individual figures. Once he began to construct his own world, as when he packs 10 or 20 figures as tight as sardines in a can, he’s back in mannerist territory, a place for which this show provides a gentle introduction.

In other words, it’s good, but it’s not the whole Bronzini. More like a tasty appetizer.