Winslow Homer: “Snap the Whip.”

If you wanted to understand American history through the typical museum installation, an odd picture would emerge. In Colonial times, it would seem, Americans were interested mostly in their own likenesses. Then, in the 19th Century, their attention shifted to grand scenery in which humans were a negligible presence. In the early 20th century, they were fascinated with cities and their crowded tenements, unsavory characters and rattling El trains.

Art history can be awfully reductive, sometimes.

For a refreshingly revisionist view, try the Metropolitan Museum’s new exhibit, “AmericanStories: Paintings of Everyday Life, 1765–1915.” There you will find a livelier history, a movie-like panorama of courting couples, contented families, rough hewn frontiersmen, awkward immigrants, shooting cowboys, small town politicians, Native Americans, and country kids playing snap the whip.

The emphasis on everyday life means you won’t have to endure presidential portraits and generals on horseback. There are very few famous people, here. Paul Revere is one, but even he is shown in his everyday role as a silversmith. Most are regular folk. The artists include John Singleton Copley. Charles Willson Peale, William Sidney Mount, George Caleb Bingham, Winslow Homer, Thomas Eakins, John Singer Sargent, Mary Cassatt, George Bellows and Frederic Remington.

Narrative art has been frowned upon since the dawn of modernism, but these painters all predate that change in taste and they milk their scenes for every ounce of drama and incident.

“The Exhumation of the Mastodon.” by Charles Wilson Peale

There’s at least a short story and maybe a novel in Peale’s “The Exhumation of the Mastodon.” Peale was one of those American Renaissance men, like Samuel F.B. Morse — also in this show. Morse took time out from painting to invent the telegraph. Peale’s extra-artistic passions were for natural history. He created his own museum where he displayed stuffed birds and other specimens as well as the mastodon bones he found in marshes near Newburgh, New York (similar specimens have been found in North Jersey).

The painting is as busy as a Bruegel, with at least 40 figures laboring around a tripod-supported waterwheel contraption for draining the swamp. Peale himself, the heroic artist-scientist, is off to one side, unfurling his drawing of the mastodon bone.

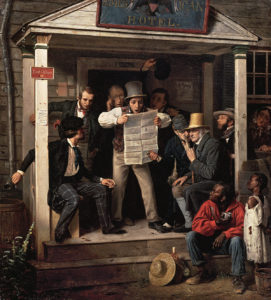

Some 19th century painters were wits with a brush. In “War News from Mexico,” Richard Caton Woodville’s captures the reaction of a group of men peering into one man’s newspaper. Perhaps their amazement is over how quickly and easily this war was won by the United States.

Bingham’s “The Jolly Flatboatmen,” looks like a scene out of Mark Twain, a beguiling image of work life on the heartland’s great rivers where there was plenty of time at midday for singing and dancing.

Remington’s “Fight for the Water Hole,” looks like a scene from the early dime novels. Paintings such as this were said to have been studied closely by director John Ford, father of the American Western movie.

“War News from Mexico,” by Richard Caton Woodville’

“The City and Country Beaux by Francis William Edmonds puts a young woman between two suitors, one a rural dandy puffing self-importantly on a cigar and the other a city sophisticate attired in black who looks like he’ll win her hand.

John Sloan, who worked as a newspaper illustrator in the early 20th Century, plucked subjects for art on every corner, doorway and rooftop. With his painterly shorthand he depicted flirtatious girls at a Bayonne picnic and a gaudy prostitute feeding a cat in a Chinese restaurant.

The show ends at the beginning of World War I, which also marked the end of the great age of illustration in this country. After this, photography would provide all the pictures for magazines and newspapers. Artist in droves joined the great adventure of abstraction.

And what happened to this vibrant strain of narrative art? It was carried forward by a stubborn handful of artists who just couldn’t let go of the image. There was Thomas Hart Benton and Edward Hopper and all those artists who did murals for the WPA in the Depression.

But the one artist who seemingly learned the most from the artists in this show, the one who was most unabashedly a storyteller, was Norman Rockwell. You can’t walk through this show without seeing where some of his ideas came from. Enormously successful as a magazine illustrator, Rockwell also spent his life trying to convince the establishment that he was a real artist, too.

And therein lies another story.