Very few 20th century artists have straddled the line between commercial and fine art. Edward Hopper did illustration work before he became successful enough in his art career to give it up. But Ben Shahn did the reverse – he took up commercial work after he had already made his reputation as an artist.

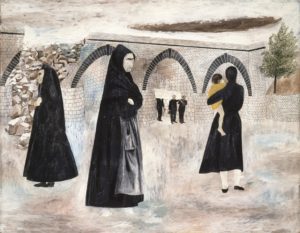

“Italian Landscape” by Ben Shahn

At the same time he was exhibiting in galleries and museums, Shahn contributed to magazines such as The New Republic, Harper’s, Seventeen, Scientific American, Time, and Nation. He did Time magazine covers of Vladimir Lenin, Alec Guinness, Adlai Stevenson, and Martin Luther King Jr.

In fact, Shahn never enforced a strict boundary between his commercial work and his fine art. He often reworked his commercial illustrations as the subject matter for his tempera paintings.

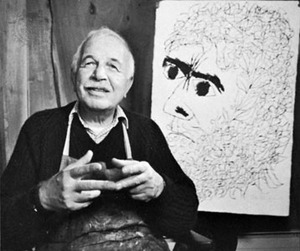

Ben Shahn

That alone would be enough for some people to dismiss him as a serious artist, and yet, Shahn’s work hangs in many, many museums and, judging by the crowds viewing his works at the Jewish Museum, he is still popular with a great many museum-goers.

People love Shahn the way that people love George Orwell – for his social conscience, for his determination to use his art for humanitarian causes. In other words, in a century where art for art’s sake has been the norm, Shahn made art for society’s sake. He came of age during the 1930s, when the Depression drew many artists into the style known as social realism. He made his reputation with a series on the executed Italian anarchists Sacco and Vanzetti.

In the latter part of his career – from the 1940s to his death in 1969 – Shahn’s work became less easy to classify. It took on a more introspective quality. He was still concerned with social issues, still took on a cause now and then, but he seemed to want to pull back from specific incidents and individuals, to make more universal statements and to deal with spiritual redemption as well as social justice.

It is this phase of Shahn’s career that is the subject of the Jewish Museum show, “Common Man, Mythic Vision: The Paintings of Ben Shahn.”

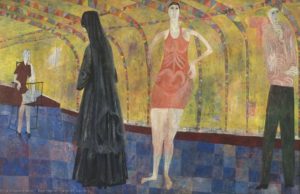

“Age of Anxiety”

Shahn was a New Jersey artist. From 1939 to his death in 1969 he lived in what was originally called the Jersey Homesteads, a housing development founded primarily for Jewish garment workers from New York City. Located in western Monmouth County, near Hightstown, it was later named Roosevelt for President Franklin D. Roosevelt, whose New Deal fostered projects such as these.

What made Shahn different from many of his socialist realist contemporaries, such as Thomas Hart Benton, was his commitment to the techniques of European modernism. You can see it in his famous Sacco and Vanzetti paintings. He simplified forms, bent space for the sake of composition, and used broad, flat areas of color.

For many people, he seemed to solve a problem – how to be modernist and still be highly accessible, or, to put it another way, how to make paintings with a strong subject matter, without ignoring all the artistic advances that began with impressionism.

In subject, the works range from nostalgic reflections on his boyhood, such as “Portrait of Myself When Young,” to responses to the harrowing effects of World War II as in the rubble-strewn “Italian Landscape,” to existential meditations such as the “Age of Anxiety” (from a poem by W.H. Auden), to works that show an interest in biblical themes and Jewish traditions, such as “Maimonides,” and “Ram’s Horn and Menorah.”

“Spring”

It’s clear from the chronological arrangement of this show that Shahn became more and more abstract in his concerns as his career progressed. In “Spring” of 1947, a painting that seems to be about postwar hope, a man and woman lie on a grassy lawn, the woman holding three flowers, the man seemingly dozing. The message is simple, the painting is insistently modernist. The woman’s red dress is a flattened-out shape, while the foreshortening is exaggerated to make the hands very large, the foot very tiny.

In “Man,” from 1952, one can see the strong influence of Picasso in his “Guernica” period. A human figure writhes on his back, hands raised in fear or agony. In a similar work from a year later, “Second Allegory,” the man writhes beneath a ghostly white hand, the hand of God perhaps, or just conscience.

There is more to puzzle over, more mystery in these later pictures than there is in the earlier socialist realist work, which often look like propaganda posters. This is true, even when Shahn was handling a social protest theme. “The Saga of the Lucky Dragon,” from 1960-62, was inspired by the fate of a Japanese fishing crew exposed to American nuclear testing in March 1954 in the Marshall Islands. The message is clear – as in one picture, where a figure lies on a hospital bed – but the mode of expression is somewhat surreal and abstract – the figure is transparent and floats in an amorphous blue field.

Shahn worked almost exclusively in tempera or gouache on board or paper, the media of the commercial artist. And yet, he used tempera in an extremely painterly way, creating expressive, multicolored passages that look very much like oil painting. But in the very same painting, Shahn will use a black contour line, like that from an ink pen, that looks very much like a style of illustration.

In this way, as in others, Shahn seems to be defying convention – resisting our efforts to fit him into one niche or the other. Is he a graphic artist or a painter? Even an admirer will have to admit that, at times, Shahn’s work looks like that of an illustrator who has borrowed certain modernist techniques, and uses them as a mere style. And, too often – as with the man writhing beneath the giant hand – his paintings have message stamped all over them.

But there is often pleasure to be had in his drawing and his use of color, and there is never any doubt about his commitment, about his need to say something about a particular subject, and that is still a rarity today.