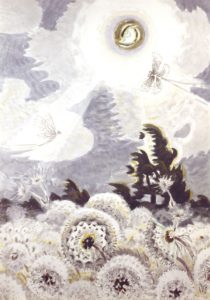

“Insect Chorus.”

Charles Burchfield (1893-1967) isn’t an easy artist to get along with. He can be revelatory but also — and there’s no way around this – strangely grotesque.

The strangeness may account for why Burchfield is not nearly as famous as contemporaries like Edward Hopper and Georgia O’Keeffe. He pushed the envelope, which shouldn’t be a problem, given today’s zeitgeist, but he pushed it in a fantasy-world direction that has never sat well, even with an envelope-pushing establishment.

There are other reasons he isn’t better appreciated: he worked almost exclusively in the minor medium of watercolor (though on a large scale); he lived a family-man’s life in upstate Buffalo; and he was a visionary who can seem more passionate – and unbalanced — than Van Gogh.

To call him a landscape painter is misleading, because it suggests that Burchfield set out to work in a conventional genre.

“How is it possible to make people understand,” he wrote in one of his journals, “that artists are not interested in art,” a statement later echoed by Barnett Newman when he said “aesthetics is to the artist as ornithology is the birds.”

Burchfield was a nature painter who dared to paint that which wasn’t visual: the songs of birds and insects, the sap moving through the trees, the mysterious life force in everything.

“Sun and Rocks.”

He was born in Ohio and went to the Cleveland Institute of Art. This was in the years leading up to World War I, a time when the tsunami of European modernism was rolling through the American art world. Like O’Keeffe, Arthur Dove, and Marsden Hartley, Burchfield took on the challenge of abstraction: how to communicate without recourse to simple representation?

One of the exhibit’s early galleries features a 1917 sketchbook titled “Conventions for Abstract Thoughts,” in which an idealistic young Burchfield tried to design a set of abstract forms to represent human characteristics and feelings. Some are cartoonish, such as “Imbecility” — a pair of ovals that look like vacant eyes — while others are farfetched, such as “Dangerous Brooding,” which looks like the yawning mouth of a lamprey eel.

In paintings such as “The Insect Chorus,” he used wavy black lines, squiggles, jagged edges and arabesques to convey the songs of crickets, cicadas and other chattering bugs. Sometimes these patterns were rendered so boldly that they obscured the vegetation the insects inhabit.

He served in World War I as an Army camouflage artist after which he spent nine years working as a wallpaper designer. During the Depression he threw in his lot with the realism-rooted “American Scene” painters such as Hopper, Thomas Hart Benton, and Grant Wood. His big watercolors lack the Western swagger of Benton or the model-train-set perfection of Grant Wood. In mood, they are closer to Hopper’s loneliness and alienation – brooding, dark-windowed churches, factory workers trudging home, and, in “Black Iron,” a hulking industrial drawbridge, a menacing thing, rendered in a watercolor with the weight and solidity of an oil painting.

In the 40s, feeling that he had lost his true path, Burchfield began to rework and expand his paintings from the late teens and ‘20s, exhorting himself to abandon realism and push further into fantasy. The paintings he did in those three decades before his death are the boldest, most transcendent and magical of his career.

At times, his efforts to go beyond appearances seem loosely grounded in scientific knowledge. He didn’t just paint light illuminating the surface of things, but light as visible radiant energy and mystical auras. The songs of birds are rendered as visible sound waves bouncing among the trees like boomerangs. In “Song of the Telegraph,” the poles and wires vibrate, pulse and hum.

“Dandelion Seed Heads and the Moon.”

All of this sounds quite joyous and life affirming. So why is there so often this sense of desolation? Why are trees always jagged and broken-looking? Why do forests have the spooky forms of Gothic architecture decorated with bat wings and spider webs?

Burchfield had a dark side. The current runs through his journals. But he also belongs to a tradition of American pantheism, in which nature – like Melville’s Moby Dick – was something terrible and fearsome as well as something beautiful. In struggling with this vision, he sometimes got lost in it.

But when he succeeded, as in his paintings of night moths and star-studded skies, Burchfield made masterpieces. In “Dandelion Seed Heads and the Moon,” the fluffy globes of the flowers are each like separate worlds, as complete and perfect as the moon hanging in the night sky. Here and elsewhere, Burchfield found salvation.