Sanford Gifford

I‘m not sure if we’ve had Indian summer, yet. Technically, a frost must pull the curtain before you can have the encore: a string of exceedingly mild, hazy days with a feeling of unreality about them. The frost came a week ago, so maybe we’re still due.

In the meantime, the visual experience of Indian summer can be had at the Metropolitan Museum in a show devoted to Hudson River School painter Sanford Gifford. Gifford had an affinity for those kinds of days, maybe because he had an Indian summer personality, a veneer of coolness layered over a poetic temperament.

He definitely had the technique down pat. He was a master at pulling veils of haze over receding hills and mountain peaks, tamping down the sun till it was just a bright blur in the western sky. Indian summer can have a narcotic effect, slackening muscles tensed for winter, and that’s what Gifford does to us. In fact, one critic of his time went so far as to compare his paintings to opium, an extreme allusion for Victorian times.

Gifford (1823-1880) belongs to the second generation of Hudson River School artists, and was the only one of the group actually born and raised in the Hudson Valley. Jasper Cropsey, Frederick Edwin Church, and Albert Bierstadt were near exact contemporaries, and it’s not clear from this admirable show why Gifford’s name should be less familiar than theirs. Perhaps it’s because people associate the Hudson River School with monumental scale and Gifford’s were never more than 60 inches wide or tall.

This is only the second Gifford retrospective since the Metropolitan’s memorial exhibition in 1880. Its 70 paintings – all landscapes – are of scenes in America, Europe, and the Middle East. Their touch may seem a bit fussy and academic by today’s tastes, but once you make the adjustment, Gifford exhibits a rare meditative sensibility that feels almost Eastern.

He was influenced by Thomas Cole, but not by Cole’s way of turning nature into an allegorical stage. With Cole, a pristine landscape hinted at the lost garden, a dead tree seemed portentous, and the course of a river — from stream to rapids to lagoon — could be the “Voyage of Life.”

Gifford seemed satisfied with the place itself. He could capture the sparkle and crispness of a freshly minted day on the banks of the Hudson, or the way naked winter branches look against a blood-red sunset, or the mist off an unrippled lake obscuring the line between water and sky. He could make you feel the soft give of beach sand under your feet (at Long Branch, then a fashionable resort), or that mild vertigo that comes with seeing immense cloud shadows sliding across a valley floor.

There isn’t a Gifford painting that won’t trigger a memory or teach you something about nature. Not all is so simple and straightforward, however. When he paints a black storm cloud arching like a tsunami over a quiet mountain lake, the sense is less of a natural event than some inner turmoil. And the more you look, the more that Indian summer haze begins to seem like something else, too. All manner of things lurk behind those veils: the iceberg-shaped profile of Mount Katahdin in Maine, the silver glint of Lake Champlain viewed from the peak of Mount Mansfield, or, strangest of all, the drop-away cleft of “Kauterskill Clove,” like some ancient sinkhole belching primeval smoke.

Wherever he went in the world – out West, the Holy Land, Italy – Gifford found the same duality. Each painting contains two worlds. There’s the vivid foreground world of splintery trees, rocky promontories, or mossy riverbanks. These are populated by tiny figures who innocently fish or picnic or crouch by a campfire. And then there’s another, more dimly perceived world, a poetic reality that is never within reach of the people within the picture, but which the artist shares with us. In El Greco, saints writhe and stretch in the attempt to experience union with the divine. Well, this is not so different, but it’s the more sublimated American version, that God-is-in-nature idea that was 19th century transcendentalism.

In the end, Gifford was not so different from Cole after all. His landscapes were equally concerned with the invisible. He just didn’t spell it out. It was both artistic strategy and temperament. He was a solitary, a Thoreau-like character who would pack up for a trip without telling anybody and return two years later just as unexpectedly; who secretly married at 53 and concealed it from his closest friends for months.

But he brought something back from his solitude. Just as the hazy unreality of Indian summer can seem like an afterlife, the mist-shrouded mountains and valleys of Gifford’s paintings are an unexpected portal, an intimation of something beyond the world of appearances.

Metropolitan Museum of Art

2003

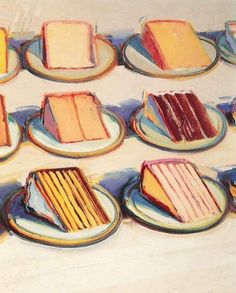

He means he’s not sure people are taking him as seriously as he wants to be taken. Thiebaud, whose five-decade retrospective is currently at the Whitney Museum, came to prominence as a pop artist in the Sixties, and has spent much of his career since then arguing that he’s not, well, exactly a pop artist.

He means he’s not sure people are taking him as seriously as he wants to be taken. Thiebaud, whose five-decade retrospective is currently at the Whitney Museum, came to prominence as a pop artist in the Sixties, and has spent much of his career since then arguing that he’s not, well, exactly a pop artist.