The countdown to the end of the century and the millennium has begun, and with the excitement about a new age dawning comes the obligation to sum up the past. It’s a big assignment, the term paper to end all term papers, but someone has to do it, and in art, the unexpected volunteer is the Whitney Museum.

Yes, the Whitney, the trendiest, the most rooted-in-the-present of our major museums, has put aside its bad-boy persona and donned its scholarly mantle to mount “The American Century: Art & Culture 1900-2000.”

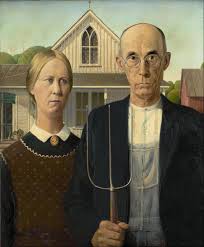

Grant Wood’s “American Gothic.”

The mammoth show, which opened this weekend, fills the entire museum, and this is only Part 1, covering the first five decades in 20th century American art. It has acres of wall text and more than 600 things to look at, watch, and listen to, for this is a multimedia presentation, with snippets of music, film clips of dancers, and a program of Hollywood movies as well as paintings, photographs, sculpture, furniture, and architectural models.

It’s a surprisingly good overview, a documentary, really, that drew on the expertise of some 60 scholars under the direction of the Whitney’s curator for prewar art, Barbara Haskell. It puts American art in the social contexts that shaped it, and, in the process, tells a story. Viewers accustomed to roaming the Whitney galleries bemused and disoriented, their logical processes subverted at every turn, will find themselves guided by a steady, coherent intelligence that takes such disparate cultural threads as social realism, abstract art, jazz, and film noir and weaves them into a tapestry of which the larger themes include prosperity, industrialization, immigration, the Great Depression, World War II, and the Atomic Age.

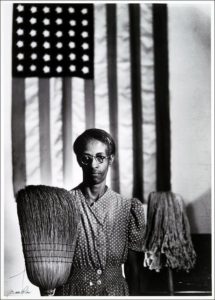

Gordon Parks’ “American Gothic.”

And, this being the late 20th century, when every enterprise has a Web site, the Whitney and its sponsor, Intel Corp., have created an elaborate on-line extension of the show that will give computer users access to more than 200 pixelated versions of the works as well as window upon window of background and historical information.

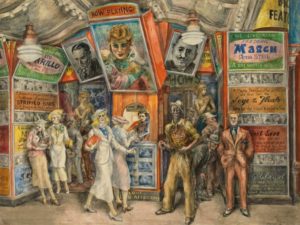

It’s a show that begins with the last flourishes of the Gilded Age, in which prosperity shines in the faces of confident and attractive society women painted by John Singer Sargent and Cecilia Beaux, and in the steely gaze of financier J.P. Morgan photographed by Edward Steichen. The sense of incredible change seems foretold by Thomas Eakins’ brooding 1900 painting “The Thinker: Portrait of Louis N. Kenton.” From there, we are off, plunging into the honky-tonk arcades and burlesque houses of Reginald Marsh, drawn into the loneliness of Edward Hopper’s automats and movie theaters, witnessing the birth of a crudely animated Mickey Mouse in Disney’s “Steamboat Willie,” staring at the parched land of Alexandre Hogue’s Dust Bowl, marveling at the campy spectacles of Busby Berkeley musicals, and feeling the terror of Robert Capa’s GI crawling through the surf on Normandy Beach.

The social history is only half of this exhibit, however. In that first gallery, among the wealthy society women, is one who looks different, who, instead of a gown with a cinched waist and a pushed-up bosom, wears what look like silk pajamas; a wealthy bohemian reclining in an artsy, affected pose with an open, vulnerable expression. She is Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, painted in 1916 by Robert Henri, a leader of the Ashcan School of painting. At a time when her wealthy compatriots were buying as many masterpieces of European art as they could get their hands on, Whitney was a booster for American art, and founded the museum that bears her name.

Reginald Marsh: “Twenty-Cent Movie”

Over the years, the Whitney has retained its founder’s devotion to art that is new, but has never done much of a job of telling the history of 20th century American art. Now, in this temporary exhibit, it does for American art what the Museum of Modern Art has long done for modernism, showing the connections between, and the progressions of, various schools of art.

The development of American abstraction, for example, is an important theme in this show, culminating, as it does with abstract expressionism, in the postwar style that made New York the center of the art world. This subplot, more difficult and intellectually challenging than the social history, could easily have been pushed aside by Mickey Mouse and Buster Keaton. But the Whitney tells it well, returning to this theme with every decade, reminding us of this thread in American art and its various manifestations – precisionism and hard-edged geometric art, organic abstraction, semi-scientific experiments with color perception, and the interest in symbol and surrealism.

These galleries present a more detached, cerebral side of the American sensibility, a world apart from bathtub gin, Charlie Chaplin’s hapless everyman, “The Great Gatsby,” or strident leftist posters. In these galleries, the big developments are the flattening and breaking up of space in John Marin’s watercolors, the careful, cautious cubist borrowings of Charles Demuth, the chromatic “synchromies” of Stanton Macdonald-Wright and Morgan Russell, the erotic botany of Georgia O’Keeffe, the interlocking symbols of Marsden Hartley, the buoyant pop imagery of Stuart Davis, and the dynamic energy of Jackson Pollock.

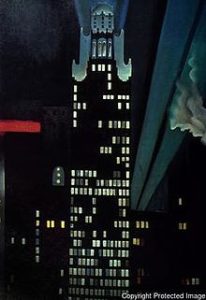

“American Radiator Building – Night,” by Georgia O’Keeffe.

The danger in trying to go beyond art and embrace all of American culture is superficiality, and there are times, perhaps, when it feels as if the net has been cast too wide. In choosing to include film clips of jitterbuggers and big band performances, of excerpts from the “Maltese Falcon” and “Citizen Kane,” in playing George Gershwin in the stairway and Johnny Mathis outside the bathrooms, the curators risk sensory overload. There’s a limit to how much people can absorb. Likewise, the inclusion of a few pieces of furniture and one or two architectural models makes it possible to list design and architecture among the disciplines covered, but it doesn’t do justice to the careers of Frank LLoyd Wright or Mies van der Rohe.

The only other problem has to do with the influence of European art on American styles. The great “isms” of the 20th century – cubism, dadaism, surrealism, abstractionism, art nouveau, and the arts and crafts movement – all originated overseas.

If painting were literature, Burgoyne Diller’s Piet Mondrian-derived grids would be considered plagiarism, but since everything in the show is American, Diller’s paintings look like innovation. The catalog corrects this problem, and the Web site presumably will, too, but those who see only the show may leave with a mistaken impression about the originality of American art.

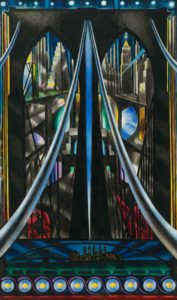

A show like this needs symbols and icons to drive home its points about American identity. The Brooklyn Bridge, late 19th century engineering marvel and symbol of progress, appears in paintings and photographs from every angle, transformed in the 20th century (like the Eiffel Tower) to a source of romantic and poetic inspiration. This culminates in Joseph Stella’s ecstatic, semiabstraction of the great bridge, a painting filled with the sound of brass, harp strings, and tugboat whistles.

Joseph Stella: “Brooklyn Bridge.”

And what better American icon is there than the skyscraper, the phallic symbol of American energy and ambition, testimony to our technological know-how? And so, skyscrapers proliferate like man-made stalagmites: Alfred Stieglitz’s and Steichen’s mist-shrouded skylines, O’Keeffe’s mystical visions of the Shelton Hotel, the precisionist’s love letters to the Chrysler Building and the Empire State, and the almost sinister architectural fantasies of Hugh Ferriss, showing the maximum masses of buildings permitted by the 1916 New York zoning law.

America as the melting pot is another iconographic theme, evidenced in the hopeful faces of Jewish and Italian immigrants photographed by Lewis W. Hine, and, conversely, in the wretched slum conditions these immigrants found, as documented by reformer-photographer Jacob Riis, whose invasive style was to burst into a room and take a picture before the occupants could pose or cover up. Tapping into the simple poetry in the everyday lives of the urban lower classes were the painters of the Ashcan School, such as John Sloan, with images of back-of-the-building clotheslines, rooftop idylls, and strolls beneath the clattering el trains.

John Sloan’s scene of a tenement clothesline.

One of the interesting lessons of this show is that for every action in art there seems to have been an equal and opposite reaction. While one set of photographers were eager to capture the here and now with photos of airplanes and automobiles, others used this extroverted medium for introversion, clouding and softening prints into dreamlike images of naked maidens contemplating glass spheres or setting them afloat in pools.

While one set of artists – the precisionists – celebrated technology and industry with Platonic idealizations of factories and machines, another set – the bio-morphic abstractionists – found something equally powerful and evocative in the shapes of plants and flowers.

While one group, the regionalists, idealized small-town life and mythic American values during the Thirties, other groups, including the urban realists, depicted the harshness of the Depression and the cruelties of capitalism. Out of this emerged a leftist tradition in American art, artists devoted to social change, such as Ben Shahn with his “Sacco and Vanzetti” series, Philip Evergood with his “American Tragedy” (a massacre of striking workers), and Jacob Lawrence’s storybook saga of black migration.

Sometimes icons seemed to give birth to anti-icons: Grant Wood’s “American Gothic” with its virtuous, pitchfork-holding Midwestern farmer was countered by Gordon Parks’ photograph of a black cleaning woman with mop and broom.

Again and again we see the faces of those whose lives were broken by the Depression: Jerry Bywaters’ dour sharecropper in front of his dying cornfield, Dorothea Lange’s quietly desperate “Migrant Mother” still clinging to hope and dignity, and Raphael Soyer’s paintings of hollow-eyed, sunken-cheeked men in soup kitchens and on unemployment lines.

In many ways, this show is like one of Thomas Hart Benton’s murals, a panorama of workers and capitalists, floozies and Midwestern moms, preachers and con men, politicians and outlaws. At the same time, it’s a tribute to American creativity, to artistic inventiveness born of the same ambitions and energy that gave rise to skyscrapers. It ends, conveniently at midcentury, with the artistic triumph of Pollock and Willem de Kooning, which put American artists in the same position of dominance as American scientists, inventors, and filmmakers.