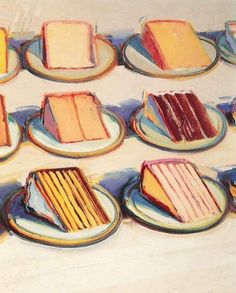

Say “Wayne Thiebaud” and very specific images come to mind: a big chocolate cake all slathered with frosting. A chunky wedge of lemon meringue. Some candied apples, glistening deep red.

All this junky food has been a mixed blessing for Thiebaud. It has meant fame and recognition. But, as he has said, “It’s not so much fun to be known as the pieman.”

He means he’s not sure people are taking him as seriously as he wants to be taken. Thiebaud, whose five-decade retrospective is currently at the Whitney Museum, came to prominence as a pop artist in the Sixties, and has spent much of his career since then arguing that he’s not, well, exactly a pop artist.

He means he’s not sure people are taking him as seriously as he wants to be taken. Thiebaud, whose five-decade retrospective is currently at the Whitney Museum, came to prominence as a pop artist in the Sixties, and has spent much of his career since then arguing that he’s not, well, exactly a pop artist.

Pop artists are cynical and ironic, and Thiebaud portrays himself as sincere, earnest. He says he actually likes all those pies, and hot dogs, and ice cream sundaes. He’s like a kid with his nose at the bakery store window. He’s the Norman Rockwell of confections.

Hmmm. Problem is, pop artists always say things like this. It’s an unwritten law that you can’t ever admit to a put-on. It’s like Andy Warhol when he used to say he “liked being bored.”

Talking about pop art can tie people in knots. But Thiebaud’s art does show something else going on, some struggle to get beyond the narrow confines of pop.

To be sure, the Whitney exhibit has plenty of food paintings: hot dogs, cakes, sundaes, cold cuts, ice cream cones, and the like (in one of the first reviews of his work, a critic suggested that Thiebaud appeared to be “the hungriest artist in California”). These date mostly to the Sixties, pop’s heyday, and, in contrast to the emotion-laden style of the reigning abstract expressionists – who agonized over every frenzied stroke – the objects are rendered coolly, with a crisp sureness of hand.

These paintings show another hallmark of pop: a fondness for repetition. There isn’t just one gumball machine but three, not one slice of pie but a dozen. As with Warhol, there’s something being said here about consumer culture and advertising.

What gives Thiebaud’s work a different flavor than pop is his painterliness and draftsmanship. In rendering a cake, he couldn’t resist using a thick impasto to mimic the icing. His drawing still shows signs of his early aspirations to be a cartoonist. He loves imparting roundness to things. There’s this little thrill you get in seeing the plane of an object turn away from you, disappearing into an illusory third dimension. It’s one of the simplest joys that drawings offer, but we never tire of it in his work, and his objects, whether a block of cheese or a maraschino cherry, seem to quiver in space, as if pleased with their own existence.

Although the cartoonishness smacks of pop, it might also be argued that we live in a cartoonish culture (especially Thiebaud’s native California), and that, like some other artists – Philip Guston, for example – Thiebaud has pushed cartoonishness into high art. He could make the contents of a candy counter or an array of cosmetics seem as stark and as lonely as anything in Edward Hopper. His light is the harsh light of a diner’s illuminated pie carousel at 3 o’clock in the morning. And beneath every pie plate or bowl of soup is a puddle of blue shadow.

Also contributing to the pregnancy of the mood is Thiebaud’s way of setting his objects against monochromatic backgrounds. He resists the draw of anecdotal painting, never gives us a sense of a room or a specific table top, or lets us see a bite taken out of one of the pies. It’s part of the pop aesthetic – like Warhol’s iconic soup can – but, in Thiebaud’s case, the blank background sets the subjects in a kind of rarefied ether in which liquidy brushstrokes caress the contour of the object, creating a halo effect.

There are probably too many food paintings in the show. You can quickly tire of all these confections, and fortunately Thiebaud found other subjects. His only real misfire was his attempt at figure painting in the Sixties. His subjects, under the same harsh spotlight, have the emotional flatness of all pop portraiture. His “Girl With Ice Cream Cone” has the scathing condescension of one of Duane Hanson’s tourist sculptures. His “Revue Girl,” with her plume headdress and fringe-adorned costume, is the human equivalent of one of his gaudy cakes.

The happiest surprise of this show are the landscapes. Some are from the Sixties, when he began doing cartoonish pastel sketches of towering Northern California cliffs and knife-edge ridges. These gave way in the Seventies and Eighties to precipitous views of San Francisco streets. These are packed with realistic details, but the verticality is exaggerated, so that streets flow straight down like waterfalls. Others are industrial and highway scenes, nightmarish nests of overlapping and coiled freeways with smokestacks poking up between the cloverleafs. These, with their smog, congestion, and gigantic scale, are the closest that Thiebaud has come to straightforward social comment.

The Eighties saw the evolution of these cityscapes into the realm of fantasy, in which buildings gaily huddle and cling to the tops of impossibly steep hills as in some Disneyesque view of Oz, or a futuristic world in which the monstrousness of overbuilding has somehow been transformed into fairy-tale grandeur.

Thiebaud’s most recent paintings are aerial views of the California countryside, the delta of the Sacramento River. These have a sense of serenity and order, like the world seen from a hot-air balloon. They are certainly his most fully composed paintings, with every part of the canvas treated with equal importance. They are also beautiful, with sinuous roads and rivers meandering gracefully across the canvas and played against sharply defined triangles and rectangles of farmland, orchards, and terraced land. The color is intense, almost psychedelic, and the parallel furrows of the fields and the ruler-straight irrigation ditches create busy patterns. Trees caught in the glow of the setting sun look like small gaseous explosions.

You can sense the pull toward pure abstraction in these pictures. Indeed, there is something of fellow Californian Richard Diebenkorn’s work in these, but unlike Diebenkorn, Thiebaud maintains a stronger grip on the visible world. He loses none of the formal power in doing so, and proves, perhaps, that finding the balance point between abstract and representational demands may be the highest art of all.

Whitney Museum of American Art

2001