Ancient Egyptian art is a marvel of consistency: a seemingly unchanging parade of cobra staffs, mummy cases, hieroglyphics and pharaonic crowns. The dates on museum labels hardly matter. What’s a thousand years here or there?

Now, the Metropolitan Museum of Art has mounted a show about an exciting period in Egyptian culture – the Middle Kingdom (2030–1650 B.C.) – when, it is said, things really did change.

Well, sort of. Change, when it happens in Egyptian art, is pretty subtle. And the 400-year flowering of the Middle Kingdom was less an artistic revolution than a glorious revival of forms from … the Old Kingdom.

Well, sort of. Change, when it happens in Egyptian art, is pretty subtle. And the 400-year flowering of the Middle Kingdom was less an artistic revolution than a glorious revival of forms from … the Old Kingdom.

No matter. This exhibit, with 230 works, is enthralling, a panorama of a culture rich in symbols and images. And one in which art played an essential part in everyday life – and death. Here you’ll find intriguing pictographic messages, charming animal sculptures, magical objects, sexy jewelry, toylike models of boats and houses, colorful mummy wraps, and the faces of pharaohs named Mentuhotep, Amenemhat, and Senwosret.

A little background. Egypt’s Old Kingdom, which built the great pyramids and the Sphinx at Giza, collapsed around 2181 B.C. In the ensuing chaos, power eventually coalesced along two stretches of the Nile River: Lower Egypt, around the old capitol of Memphis, and Upper Egypt, around the city of Thebes. After about 100 years, Lower Egypt fell to the armies from Thebes and the Middle Kingdom was born.

In the first gallery, you can see pharaohs wearing the new “double crown” to symbolize unification of the two kingdoms. The elaborate headgear combines the white cone-shaped crown of Upper Egypt inside the red flat-topped crown of Lower Egypt.

One innovation of the Middle Kingdom was a new genre of sculpture called the block statue in which a seated human figure retained the rough shape of the original stone block. Subjects were rendered as if wrapped in a sheet with their knees drawn up. Their protruding heads and feet make them look like hunkering birds, but the taut fabric between the legs made a good flat surface for hieroglyphs.

You learn more about people’s families in Middle Kingdom art. The limestone stela of the “Trustworthy Sealer Seneb,” organized into panels like a comic book page, shows the entire family of the deceased. A stela for a mother who died very young includes an image of her child on the lap of a foster mother, as if to reassure everyone that the baby was being cared for.

Despite their somber function, these tablets are wonderfully lively. incorporating pictographs of eyes, jackals, birds, cobras, beetles and human figures. You may wonder why the counterparts in our culture – gravestones – are so comparatively devoid of anything celebratory or descriptive.

In a gallery devoted to “Royal Women,” you’ll see jewelry worn by a Princess named Sithathoryunet, a relative of King Amenemhat III. In addition to bracelets, anklets, and a pectoral necklace, she wore a hip girdle made of stones and cowrie shells. The shells had erotic associations and were filled with pellets that made a soft sound when the woman walked or danced

Overall, this is not a King Tut type of show, not one that bedazzles with royal luxuries and weighty objects of solid gold. There’s a much bigger cross section of Egyptian society. Many pieces were made for officials in the Middle Kingdom’s vast bureaucracy, such as the powerful vizier (like a prime minister) and the high steward (like a secretary of agriculture). A statue of a bald portly man with powerful arms had the title of “reporter,” the equivalent of today’s press secretary.

A painted relief immortalizes a seemingly unglamorous event, a government inspector’s tour of food and manufacturing facilities. Tellingly, his entourage includes several bodyguards, a man wielding an ax (for breaking down doors?) and his spotted dog, Ankhu.

Other characters who populate this show include a seal bearer, butler, chamberlain to the treasurer, storage overseerers, servants, musicians, dancers, jewelers, nurses, and a class of person described as “elite women of the provinces.”

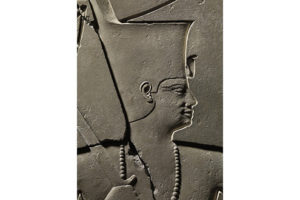

At the pinnacle of this society was the pharaoh, who was represented somewhat differently in the art of the Middle Kingdom. Instead of the idealized personages of the Old Kingdom, these new pharaohs have individualized faces.

“Amenemhat III Wearing the White Crown,” shows a man with prominent cheekbones, almond-shaped eyes with pouches underneath and crisply outlined lips. It’s hard to tell how old he is supposed to be. His skin appears smooth, but also loose on the bone.

No one knows if this is an accurate representation of the pharaoh, but the realism is telling. It seems to reflect a new attitude, an open acknowledgement that the pharaoh, though still technically a god, is also a regular human being. And in ancient Egypt, that really was a big change.

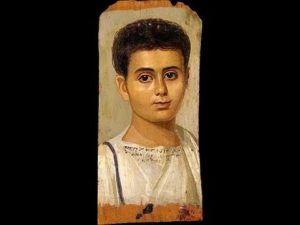

However, although they may have adopted Roman ways, and although many of these people may have been of mixed ethnicities (Roman Egypt was a truly multicultural society), they clearly retained traditional Egyptian religious beliefs about the afterlife, or at least felt connected to Egyptian traditions. The most vivid of these portraits were done in encaustic, a beeswax-based medium that resists drying, fading, and cracking. At the same time, the waxy paint retains the brush strokes, and gives these works a directness and painterliness that looks almost modern.

However, although they may have adopted Roman ways, and although many of these people may have been of mixed ethnicities (Roman Egypt was a truly multicultural society), they clearly retained traditional Egyptian religious beliefs about the afterlife, or at least felt connected to Egyptian traditions. The most vivid of these portraits were done in encaustic, a beeswax-based medium that resists drying, fading, and cracking. At the same time, the waxy paint retains the brush strokes, and gives these works a directness and painterliness that looks almost modern.

It requires something of an adjustment, then, to get in the right frame of mind for “Egyptian Art in the Age of the Pyramids” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. For the art on display seems to have been produced by a people who had a confident, positive outlook on life; who had strong bodies and alert, satisfied expressions; who took pleasure in their work; who were tender and affectionate with one another, and who lived in a bountiful environment teeming with wildlife, birds, and fish.

It requires something of an adjustment, then, to get in the right frame of mind for “Egyptian Art in the Age of the Pyramids” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. For the art on display seems to have been produced by a people who had a confident, positive outlook on life; who had strong bodies and alert, satisfied expressions; who took pleasure in their work; who were tender and affectionate with one another, and who lived in a bountiful environment teeming with wildlife, birds, and fish.