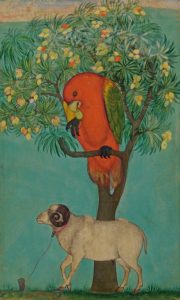

You can practically smell the incense and mango blossoms at the Metropolitan Museum’s exhibit of art from India’s Deccan peninsula. It’s a fairytale world, one in which the protagonists wear golden boots, ride on elephants, wander through enchanted gardens and recline on canopied thrones. It’s also a topsy-turvy one in which diamonds are as big as peach pits, falcons wear pendants and parrots are bigger than rams.

Along with the pleasant disorientation that comes with such a show, are the historical challenges. Even after reading the introductory wall-text, you keep asking yourself: Who were these people? When did they live? How did they get to the middle of India?

As its title suggests, “Sultans of Deccan India, 1500-1700: Opulence and Fantasy,” is about an Islamic civilization that took root on the Deccan Plateau, India’s broad midsection. It was an offshoot of another Islamic civilization, the Mughal Empire, to the north, which conquered the plateau, but couldn’t hold onto it. The Deccani settlers rebelled against the imperious Mughals and established the independent kingdoms that are the focus of this show: Bijapur, Ahmadnagar, Bidar and Golconda. What evolved was an unusually cosmopolitan society and – thanks to diamonds and other lucrative trade – a very prosperous one.

The huge diamonds, which open the show, are suitably stunning, although the Deccan taste was originally for flattish, rectangular diamonds as clear as glass. Later, European taste resulted in the multifaceted, glittering stones familiar to us today, such as the 70-carat “Idol’s Eye” diamond that, centuries later, was set into a necklace by jeweler Harry Winston.

Paintings are the true jewels here, however. They are small, like Persian miniatures, painted on paper. Many are no bigger than a sheet of typing paper, with details that they can only be fully appreciated with the aid of a magnifying glass (helpfully provided in the galleries).

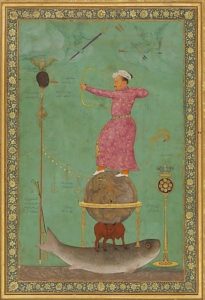

For an idea of just how multicultural this society was, consider Malik ʿAmbar, an Ethiopian slave who rose to be a general and prime minister of Ahmadnagar. In one painting, he stands in profile, a formidable, large-bellied figure wearing gauzy white robes and holding a long Decanni sword. A master of guerilla style warfare, he so infuriated the aggressive Mughal sultans to the north, that one of them, Jahangir, dreamed that he was shooting an arrow through Malik’s decapitated head. The dream remained an impotent wish, though immortalized in a surreal picture by Jahangir’s own court painter. The pink-robed sultan lets his arrow fly while standing atop a globe of the earth, which rests on the back of a bull, which itself stands on a giant fish.

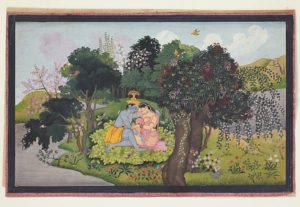

That’s about as weird and as violent as the imagery gets in this show. Whatever wars were waged by the sultans of Deccan India, they wanted to be remembered for their elegance, refinement and spirituality. Sultan Ibrahim ‘Adil Shah II of Bijapur was an accomplished musician, composer and visionary. We see him riding an elephant, playing a string instrument called a tambur, and strolling trancelike through a breezy night garden holding castanets that look like colorful birds.

Sufis, mystics of the Islamic faith, had a status in Decanni society that transcended royal and political power. In another painting of Sultan Ibrahim, he is shown bringing gifts, including a spittoon, to a rather elegant sufi who wears a turban, holds pince-nez and sits on a canopied throne.

In contrast, a sufi leading a more ascetic life (usually called a dervish), is portrayed on a hillside sitting on a tiger skin. His power is such that two lionesses lie tamely at his side. A yogini approaches in a prayerful attitude. There are several paintings like this in which holy men and women from different disciplines interact, another reflection of Deccan society’s liberal nature.

There are some amazing objects in this show: a falcon constructed entirely of metal calligraphy, a tall, delicate brass ewer with an elongated dragon-head spout, a sculpture of a mythical winged lion slaying six elephants, a peacock-shaped incense burner and immense tapestries chock full of passages reflecting the rich life of the Deccan peninsula.

But the soul of this show is in its poetic paintings. One of the most evocative is just a fragment. Titled “Peacock in a Rainstorm at Night,” it shows the turquoise bird diving for the treetops where smaller birds are already sheltered. It’s monsoon season. The bird’s multi-eyed ornate tail stands stark against landscape shrouded in utter darkness. The horizon’s sharp curve makes the earth seem small as it meets the menacing, cloud-filled sky.