“Portrait of the Imperial Bodyguard Zhanyinbao”

In the year 1744, the emperor of China began work on a beautiful garden in the Forbidden City. There, he imagined, he would retire to a life of contemplation and literary pursuits.

“In my eighties, exhausted from diligent service,” wrote the Qianlong emperor in one of his many poems, “I will cultivate myself, rejecting worldly noise.”

Unfortunately, the Emperor never got to live out this ideal retirement. He remained saddled with the burdens of imperial rule until his death in 1799. His masterpiece, the Qianlong Garden, fell into two centuries of disrepair and overgrowth.

Yet there was a silver lining to this. Unlike the creations of so many other Chinese rulers, which were updated or demolished by their successors, this one remained a time capsule, reflecting 18th century taste at its most extravagant.

Now, an ambitious restoration in Beijing has freed up some of the garden’s interior artworks for loans. The result is “The Emperor’s Private Paradise: Treasures from the Forbidden City” at the Metropolitan Museum. On view are paintings, calligraphy, ceramics, clocks, rootwood furniture and decorated panels, screens and partitions.

The exhibit is as much about the place as its 90 precious objects. This was no mere garden in our narrow sense of the word, but an elaborate, though compact compound of buildings, pavilions, and landscaping. It wasn’t a place for appreciating pure nature so much as a refined fantasy of it.

Even the the names of the buildings are dreamy: Building of Luminous Clouds, Pavilion of Soaring Beauty, Lodge of Bamboo Fragrance, Belvedere of Viewing Achievements, and (on the theme of the well-deserved retirement) the Studio of Exhaustion from Diligent Service. It was a place where the emperor could be entertained in his private theater, but it was also a place where he could play the rustic and – like Marie Antoinette in her peasant cottage at Versailles – pretend to be a simple hermit contemplating the moon.

Although permanent retirement to the gardens was never in the cards for the emperor, he was able to enjoy it over the last 20 years of his life for brief visits or weekend-like retreats. Such occasions may have been an opportunity to get away from the imperial throne, but apparently an emperor couldn’t sit on anything else, since thrones occupied every important space.

Because he had a summer palace, and was expected to use the garden during the cold months, winter themes predominate in decoration, particularly what Confucious called “The Three Friends of Winter.” These were bamboo and pine, which stay green in winter, and the plum tree, which blooms in late winter.

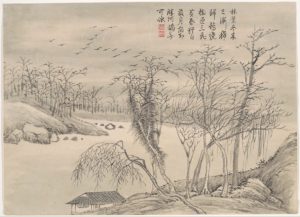

“Winter Landscapes and Flowers”

A portrait of the Qianlong emperor shows a long-faced man with jowls and a direct, penetrating gaze. A contemporary of George Washington, King George III of England, Catherine the Great, and Louis XV, he ruled an empire that was the richest and biggest in the world. And yet, he found time to be a literary scholar and the author of an incredible 40,000 poems.

For all his devotion to Chinese aesthetics and philosophy, the Qianlong emperor was also intrigued with innovations from Western art. European artists were brought over to teach and execute perspective and other realist techniques. Most often the Chinese artists blended the two methods, as in the emperor’s portrait, in which the voluminous robe is rendered flat, while the face is modeled three-dimensionally. Trompe l’oeil wall paintings were used to create the illusion of space in the rooms of the small garden buildings.

The Chinese lacked the technology to produce glass, hence imported glass was highly valued and used in art alongside gems and other precious natural materials, as in a panel depicting a plum tree, in which the petal-blossoms were fashioned from milky glass.

Among the religious works are a series of 16 panels depicting enlightened Buddhist disciples. These “ luohan” are rendered in white jade set into a black lacquer background. The starkness only emphasizes how outlandishly ugly they are, a reminder, perhaps that wisdom has nothing to do with external appearance or conventionality.

Until they were taken out of their settings during restoration, no one knew that the backs of these panels were decorated with 16 different, elegantly rendered plants – perhaps representations of the inner perfection of those on the reverse side.