Indian painting is pure pleasure. You don’t need to know any theories, art history or even the subject of the picture. You look at these paintings like a child peering into an illustrated book of fairy tales.

It’s an art of heroic feats, courtly love, eroticism, the thrill of battle, palace intrigue, fantastic gods, beautiful animals and haunting landscapes.

Abd-al-Samad’s “Two Fighting Camels”

I don’t know why there aren’t more exhibits devoted to this magical tradition. Perhaps because the works are small and on paper. In our culture, images that aren’t big and on canvas are taken less seriously. But now the Metropolitan Museum of Art has stepped up with a beautiful show covering eight centuries of Indian miniatures. It takes you from works done on palm leaves in the 12th Century through the great golden age of the enlightened Mughal emperors, and ends with the introduction of photography and the tradition’s decline in the late 19th Century.

“Wonder Of The Age: Master Painters Of India, 1100-1900,” also has a different spin than other such shows. Instead of organizing the works by style or dynastic periods, the focus is on 40 artists and their lineages. Some are still nameless, known only as “master of” this or that style or tradition, but others emerge as individuals, such as Basawan, favorite of the Mughal emperor Akbar, whose style was influenced by European realism. Or the Iranian-born, Farrukh Beg, whose style reflected the Persian penchant for poetic and complex landscapes of stylized mountains, trees and flowers.

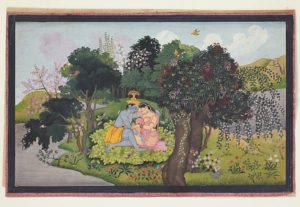

“Krishna with Radha in a Forest Glade”

There are just enough pieces from the early centuries to give a sense of what Indian painting was like in the pre-Mughal era, when Buddhist and Hindu themes were treated with intense color and emotion to match. In “Green Tara Dispensing Boons to Ecstatic Devotees” by the artist known as the Mahavihara Master, the goddess is a voluptuous giantess surrounded by fervent followers.

Indian art excelled at animal paintings. In ‘Abd-al-Samad’s “Two Fighting Camels,” each animal has the other’s leg in its mouth. Elephants are depicted both naturalistically and in ornate costumes riding into battle. The Indian Audubon was an artist named Mansur, whose precise renderings included two peafowl, a yellow-beaked great hornbill and a green chameleon.

For a sense of the refinement of art under the Mughal conquerors, consider the elegant profile portrait, “Shah Jahan Riding a Stallion,” by the artist Payag. Imperial power (and exquisite taste) are expressed in jewel encrusted scabbard, the saddle like a small pile of Persian rugs, and, a gold halo like those worn by saints in Western art.

Popping up all over the show is the blue-skinned Krishna, both Hindu god and an historic figure. He is already a hero in infancy, as in “Nanda Touches Krishna’s Head after the Slaying of Putana,” an illustration of an episode in which the babe kills a demoness by draining life from her breasts. This picture, from the Delhi-Agra area of North India, gives everyone the same black-lined almond-shaped eyes typical of Indian art.

Krishna, not to be confused with Rama, who is also blue, was something of a prankster in his adolescence, as can be seen several versions of the story in which he perches in a tree with the clothes of the gopi, or cow-herd girls, who are bathing in the river. Later, you can see him as the sensuous lover of the lovely Radha in “Krishna with Radha in a Forest Glade,” in which the flowers and blossoming trees around the two lovers seem expressions of their awakening passions.

The show draws to a close in the late 1800s, with what came to be called “the company school,” a reference to the East India Company, which virtually ran India when it came under British rule. Some of the works commissioned by the British look like European ethnographic studies, although the Indian artist who painted “Four Tribesmen,” portrays the men with great empathy. The camera came into play with hand-colored photographic portraits that are beautifully done but can’t help but be jarring after the dreamlike world of the paintings.

Perhaps panoramic photography inspired the 1893 painting, “Maharana Fateh Singh’s Hunting Party Crossing a River in a Flood,” a watercolor that is more than 5 feet wide. If so, no magic was lost, for this is a hauntingly beautiful picture with its long procession of riders and the sky lit by a lightning bolt that looks like a golden serpent.