Things are never what they seem in Japanese narrative art. Shipwrecked men are attacked by demons disguised as beautiful women. A fisherman’s wife is revealed to be a turtle. The dead return or have interesting adventures in the netherworld.

Welcome to the fantastic world of emaki, illustrated handscrolls that date back to Japan’s middle ages. Some 20 such scrolls are the focus of “Storytelling in Japanese Art” at the Metropolitan Museum. Together with decorative screens, fans and books, they provide insight into the origins of those popular Japanese comic books called manga and, in turn, the graphic novels of western culture.

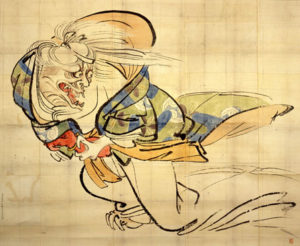

Shibata Zeshin, “The Ibakari Demon.”

Although most emaki have a god or two, or at least a bodhisattva, few are solemn or meditative in character. They are much more like Grimm’s fairy tales than religious stories. And the artists have pulled all the stops in renderings of monsters, hellfire and gory details.

Consider, for example, “The Drunken Demon,” in which five warriors are sent to the castle of a monster who has captured all the region’s beautiful young women. Upon arriving, the giant monster serves them a feast of sashimi of human flesh to be washed down with goblets of blood. Later, with help from the gods, the heroes break into the demon’s bedroom and chop off his head. The huge head flies through the air and plops atop a hero’s head, which, we are told, would have killed him had he not been wearing a god’s golden helmet.

Sheerly in terms of artistic value, the heroes are no match for the slavering, bug-eyed, snaggle-tooth monsters. Upon these, the artists have lavished all their skills. The humans – small, berobed, dignified – are as static as chess pieces by comparison.

In “Legends of the Kitano Shrine,” a story of vengeance, the visual stars of the story are the gigantic Thunder God who scatters the wrongdoers like so many leaves in a hurricane and an eight-headed beast who guards the fiery gates of a blast-furnace Hell.

Anonymous, “Illustrated Legends of the Kitano Tenjin Shrine.”

Next to the monsters, the landscapes are the most visually fascinating. This form evolved out of landscape scrolls that were made to be experienced as a journey through poetic scenery. As the viewer rolled out a foot at a time – from right to left — he would follow a path through forests and mountains while passing lakes, wildlife and picturesque shrines. The convention continued into the narrative versions, requiring artists to connect disparate landscapes to tell the story (unlike contemporary graphic stories, there are no frames to separate the scenes). Hence, for example, a line that represents the bottom of a cloud might gradually become the horizon for a sea voyage as the action unfolds.

The scrolls are typically 30 to 40 feet in length – much too long for museum cases to display. This is the exhibit’s only shortcoming – that you can see only a segment of each scroll. Most stories consisted of three rolls, so what you see is like the coming attractions in a movie, a synopsis and three scenes. A few of the stories can be seen in their entirety on touch-screen computers in the final gallery.

In addition to themes of war and horrible monsters, there are religious stories about miraculous events, love stories involving courtiers and court ladies, and comical tales in which animals, like mice and foxes, stand in for humans. It is worth revisiting, not only because there is so much currently on view to absorb, but because in February, some 20 new works of art will be rotated into the exhibition.