It’s easy to gloss over the subtitle of the Metropolitan Museum’s blockbuster Afghanistan exhibit, “Hidden Treasures from the National Museum, Kabul,” because museums are always promising viewers “rarely seen” or “hidden” treasures.

But this is one case where “hidden” is the literal truth. What you see in this dazzling show of gold and glass and ivory are works that were concealed in trunks during years of war, terror, looting and the intentional destruction of art. This is a country, remember, where bombs and mortars have been exploding since the Russian invasion of 1979 and where, in 2001, two gigantic Buddha statues were dynamited to bits — part of a Taliban program to purge the culture of forbidden images.

Fortunately, back in 1988, officials from the country’s National Museum had secretly stashed more than 20,000 treasures inside the subterranean vaults of the Central Bank of Afghanistan. Most people assumed they were lost, so it was a global event in 2003 when the secret was revealed and the crates were opened. The waves of excitement sent these objects on a tour through Europe and now America.

The ongoing war in Afghanistan gives the art in this show an element of political symbolism. You’re aware that this is art rescued from tyrannical ideas, art that has been at the crux of a fight for freedom. At the same time, it’s art that that few Americans have the foggiest idea about, art from “archaeological digs” created by and for people dead for thousands of years.

All this might seem to add up to a rather solemn, dutiful experience – looking at pot shards and indecipherable tablets while feeling vague stirrings of patriotism. Fortunately, it’s nothing of the kind. Organized by the National Geographic Society, this is a show with the popular audience in mind. The dark, dramatically lit installation is alluring and mysterious. It dips into four lost cultures, spotlighting objects that are both beautiful in themselves and evocative of their time and place. Maps, photographs, computer animations and a short documentary film satisfy provide helpful background information.

There is no way to simplify Afghanistan’s history. In the ancient world, the country was three distinct lands: Bactria (northern Afghanistan, Aria (Western Afghanistan) and Arachosia (southern Afghanistan). Over the millennia, it has been conquered by a host of people, including the Median and Persian Empires, Alexander the Great, the Seleucids, the Indo-Greeks, Turks, and Mongols. Its predominant religions have alternated between Zoroastrianism, Hinduism, Buddhism and Islam. The legendary Silk Road that passed through it brought a continual influx of goods and cultural ideas.

All this makes for art that confounds expectations and is even pleasantly disorienting. The oldest pieces date to 2000 B.C., and include a fragment of a gold bowl that was found intact in 1966 near the Oxus River. Unfortunately, the farmers who came upon it chopped it up with an ax to divide the gold. But the imagery survives, included that of bearded bulls, a popular motif in Mesopotamian art.

Capitals from Corinthian columns and classically sculpted stone faces might make you feel like you’ve dropped downstairs into the Met’s Greek and Roman Galleries. These pieces are from Ai Khanum, a Hellenistic colony founded by Alexander in 327 B.C. before he led his armies toward India. The city had the traditional Greek amphitheater and gymnasium, but, as a computer animation shows, it retained the grand, palatial style of the region’s previous rulers, the Persians.

From excavations at ancient Begram, a once-major stop on the Silk Road (now a village north of present-day Kabul), come some of the most startling objects in the exhibit. All are from two sealed rooms that archaeologists believe might have been a merchant’s storehouse. If so, he was dealing in luxury goods. Many are ivory, such as the voluptuous woman standing on a fantastic crocodile creature, which was carved from a single tusk in a distinctly Indian style.

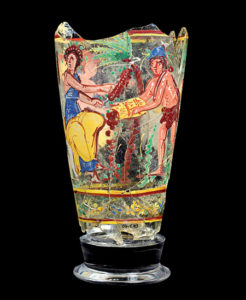

From these same rooms come colorful Roman glass vessels like the yellow-and-blue flask in the shape of a fish and a painted beaker showing figures harvesting dates done in such a relaxed style and in such bright colors that you can’t help being reminded of those glasses kids bring home from fast-food restaurants.

No one held power for long in Afghanistan and Bactria was overrun by invading nomads in about 145 B.C. Historians refer to this as a dark age, because the nomads seemed to bring little culture to replace that of the Greeks or the Persians. Ironically, these peoples are the focus of the fourth, and most glittering section of the exhibit, which evokes six nomadic tombs in which the bodies were laid out wearing gold jewelry and ornaments.

These gold pieces – including clasps, hair ornaments, brooches, plates, sheaths, belts and tiny coin-like amulets called bracteates – are inlaid with turquoise and garnets and are crafted with surprising delicacy. They are laid out on black velvet in patterns that replicate how they were found on the bodies, creating a tomb-like atmosphere. The highlight of this section is a fantastic crown cut out of gold leaf and decorated with rosettes and dangling roundels.

The crown provides the last of the exhibit’s multicultural mysteries: crowns of this type have been found in tombs in the Silla Kingdom in Korea dating to the fifth and sixth century A.D.