Matthew Barney

It’s not easy being a famous artist today. To command the necessary attention, to poke your head above the rest of the scrabbling crowd, you must be utterly, even flamboyantly, outrageous. No halfway measures will do. You must be willing, for example, to strip naked, don a mountain-climbing harness, and clamber around on an art gallery ceiling with titanium ice screws dangling from your anus.

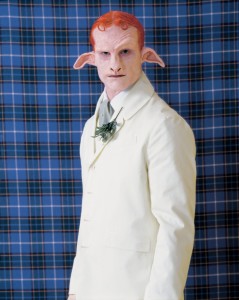

A still from Matthew Barney’s “The Cremaster Cycle.”

But here’s the hard part, that which separates the men from the boys. You must maintain an attitude of utter seriousness. You can’t refer to what you’ve done as a “happening,” as earlier artists

innocently called such stunts. You must give it a title that is at once enigmatic and scientific, such as “Blind Perineum.” And it must fit into a theoretical framework that transforms the act into something profoundly symbolic, having to do with “pulsating cycles of desire and discipline,” or “the permeable membrane between the human and the inhuman.”

So began the exemplary career of Matthew Barney, who, a mere 12 years after this auspicious debut, is hailed by critics as a genius and “the most important artist of his generation.” His Wagnerian-like masterpiece is “The Cremaster Cycle,” a series of five feature-length art films, wordless but visually extravagant, a new millennium mix of biology, mythology, and autobiographical symbols in which Barney plays a satyr, a ram, a magician, Harry Houdini, and the murderer Gary Gilmore.

All five films are showing continuously at the Guggenheim Museum, both in its auditorium and on monitors in the main spiral exhibition space, where also can be found related sculptures and props from the films, including a concrete-filled piano and a trough filled with molten Vaseline.

Now for the impressive bio. Bright, athletic, and handsome, Barney went from Boise, Idaho, to Yale University on a football scholarship and supported himself with modeling jobs. He graduated in 1989, and that very same year, performed his first major video, “Field Dressing,” in which he slid up and down a metal pole, scooped up petroleum jelly, and repeatedly pushed it into all the orifices of his body. After clambering naked on the walls and ceiling of the Barbara Gladstone Gallery, Barney did a piece called “Radical Drill,” in which he performed football blocking exercises dressed in high heels and a black evening gown. By 1993, he was in the Whitney Biennial with a video, “Drawing Restraint 7,” in which Barney plays a goat-boy limo driver of indeterminate sex who chauffeurs two older satyrs around Manhattan’s tunnels and bridges, while the two old goats wrestle in the back.

The title of “The Cremaster Cycle” comes from the name for the muscle in the male reproductive system that raises and lowers the testicles in response to temperature changes, external stimulation, or fear. Another theme that fascinates Barney is that moment in fetal development when the male and female sexual organs differentiate. In one film, chorus girls do a Busby Berkeley routine on a football field, forming shifting outlines of reproductive organs.

The other films play out these themes, blending them with ancient myths and modern film genres and a host of bizarre and kitschy characters who cavort about in strange, architectonic environments that are themselves symbols of anatomical structures and psychological constructs. “Cremaster 2” is a gothic western based loosely on “The Executioner’s Song” by Norman Mailer, who plays Harry Houdini in the movie. It tells the story of convicted murderer Gary Gilmore, said to be Houdini’s grandson, who was put to death by a Utah firing squad in 1977.

The third “Cremaster” film is a gangster thriller about Masonic initiation rites, zombies, and the construction of the Chrysler Building — which functions as a character in the story. One sequence has dead horses (wearing body costumes to simulate rotting flesh) racing at Saratoga. In the fourth, set on the Isle of Man, Barney plays a dandified, tap-dancing satyr, who writhes his way through a treacherous underwater canal. “Cremaster 5,” performed in a Hungarian opera house, stars Ursula Andress as the lovelorn queen and Barney as the diva, the magician, and the giant, and features hermaphroditic water sprites in a bubble bath.

What kind of artist is Barney? Despite all the postmodern theory and esoteric biology, Barney he has a lot in common with the good old surrealists. His films work more like dreams than any dramatic or narrative form, and, like the surrealists, who paid homage to Freud and the Marquis de Sade, Barney is preoccupied with sexual development and orifices.

His surrealist progenitor might be Salvador Dali, the most outrageous, sex-obsessed, and narcissistic of them all. Dali had a hyperactive imagination, and the ability to realistically render any paranoid or infantile fantasy that flitted across his mind, so that, no matter how weird the subject—the giant grasshoppers and limp clocks—he won people over with his polished technique.

Dali was, of course, a flamboyant and eccentric personality, which the deadly earnest Barney is not, despite the nude cavorting. Dali, for all his pompous claims of genius, was too madcap to consistently take his own nonsense seriously. When asked by visitors to his exhibits about the meaning of works with such titles as “Debris of an Automobile Giving Birth to a Blind Horse Biting a Telephone,” Dali would respond with even more ridiculous commentary, such as “the telephone represents the blackened bones of my father passing between the male and female figures in Millet’s ‘Angelus.'”

It makes you long for the good old days.

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

2003