In 1977, I went to see a Balthus show at the Pierre Matisse Gallery. It was a weekday afternoon, midway through the run of the show, but the 57th Street gallery was packed —mostly with young artists. Nobody could afford to buy anything, yet there was no sense —as you sometimes get in uptown galleries—that the crowd with the paint-splattered jeans wasn’t welcome.

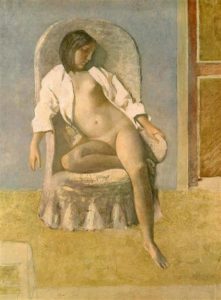

“Nude at Rest,” 1977, by Balthus

The gallery had an air of noblesse oblige. It dealt in legends, the big European names of the century: Joan Miro, Alberto Giacometti, Marc Chagall, Pablo Picasso, Georges Rouault, Balthus, Jean Dubuffet, and, of course, Henri Matisse, the artist’s father. Although many of the artists were part of history by that time, there was still a sense of a living connection, of being closer to the source than was the case in a museum.

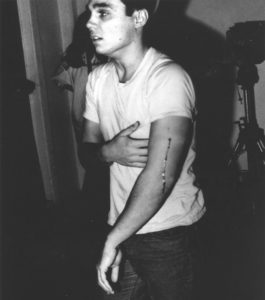

Balthus, for example, was a touchstone for many artists at that time, a painter who had found a way to reconcile the great figurative tradition of the past with a modern sensibility, in works that were elegant, mysterious, and sexually charged.

Being an art dealer when your father is a famous artist might seem to solve several problems – name recognition, for example, or access to blue chip art. And to some extent, Matisse did benefit from his connections. But Matisse was determined to carve out his own identity. He chose his own turf, leaving France for New York in 1924, and after some apprentice years, opening up his own space in the Fuller Building on 57th Street.

Between 1931 and 1989, Matisse organized hundreds of exhibitions. Artists whose names are golden to us today owe much of their glitter to Matisse’s patient burnishing. In 1945, he was the first to exhibit Miro’s “Constellations” series; in 1948 he mounted the first retrospective of sculpture by Giacometti, and in 1949 gave the world its first look at his father’s famous cutouts.

The Morgan Library, which normally deals with books and drawings, organized “Pierre Matisse and His Artists” because in 1998 it was given the gallery’s archives. So, in addition to about 60 paintings by gallery luminaries, there are letters, show announcements, checklists, photographs, and other memorabilia that provide glimpses into the workings of the gallery.

The show is unusual for its focus on a dealer. Art dealers tend to get much less attention than the impresarios of theater and dance, even though they do the same thing: find talent, develop it, bring it to the public, and change people’s tastes.

Matisse was known for his remarkable eye and his low-key salesmanship. He never relied on theory or fashion to tell him what was good. He embraced the refinement of Balthus and the harsh primitivism of Dubuffet, the whimsical abstractions of Miro, and the obsessively analytical portraits of Giacometti. Clients guided by his taste included Walter P. Chrysler, Joseph Pulitzer Jr., Edward G. Robinson, and James Thrall Soby. Two of his collectors endowed their own museums, Joseph R. Hirshhorn and Duncan Phillips.

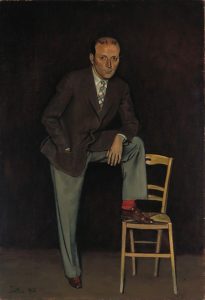

His face peers out at us from several paintings, filtered through the lenses of his artists’ sensibilities. The earliest, by his father, is a charming oil of 9-year-old Pierre, wearing a pinkish cap. With a few sure lines, the elder Matisse captured his youngest son’s slightly divergent eyes and the serious expression that he would carry through his life.

A 1938 standing portrait by Balthus is the epitome of panache and sophistication. The handsome young dealer with the thinning hair, the soulful brown eyes, the stylish clothes stands with one foot up on a chair, revealing – like the bold touch of color in one of his father’s paintings – a bright red sock.

Dubuffet, the art brut visionary, depicted his dealer as a greenish light bulb with a worried expression.

Relationships with artists were fraught with tensions. There were issues over contracts, monthly stipends, the scheduling of exhibits, the setting of prices. Sculptor Alexander Calder, for example, quit the gallery after a dispute about money. Calder refused to part with his works at the prices Matisse wanted to sell them for, although they weren’t moving well at the higher prices. Matisse wrote back, “I always thought that prices were raised by the demand!”

Balthus managed to take offense when Matisse didn’t enthusiastically agree to sit for another portrait, writing to his dealer: “The very spontaneity of your reaction made me realize … that you are really no longer interested in my work, apart from its business potential.” Matisse managed to patch this one up.

How much the finances of the art world have changed can be seen in a 1943 poster for a summer exhibition that trumpeted, with uncharacteristic commercial zeal, “Modern Pictures Under Five Hundred,” with a list of names that included Picasso, Amedeo Modigliani, Pierre Bonnard, Chagall, Andre Derain, and Matisse.

The war years depressed prices for art, but they also sent more European artists Matisse’s way. A 1942 “Artists in Exile” exhibit featured, among others, Chagall, Piet Mondrian, and Yves Tanguy.

Matisse was oriented toward European art, but he was also a New Yorker and not so Old World as not to appreciate art rooted in his adopted city, such as Raymond Mason’s funky sculptural tableau of St. Mark’s Place, circa 1972. The scene, a view from a coffee shop window, is a parade of characters and grotesques – winos and panhandlers, flower children and aging hipsters, people in turbans and plumed helmets – set against perfectly rendered store facades with the squalid tenement windows above.

Matisse took chances on new artists and, once committed, worked to boost their careers to the next level. The sale of a major painting by the young Cuban painter Wilfredo Lam to the Museum of Modern Art was a huge breakthrough, worthy of a telegram to the artist.

There are some beautiful individual works in this show. The Balthuses are great, including several of dreamy, somnambulant girls and a window-framed view of the French countryside with a magical, almost granular light. Miro’s blue-field “Constellations” are pure joy, and there’s a wonderfully elongated Chagall acrobat in harlequin-patterned tights.

But, this exhibit is mostly valuable for the way it illuminates the sensibilities of an art dealer who enriched the cultural life of New York City for more than half a century.

The Morgan Library

2002