Scaring people has always been one of art’s primary functions. Aristotle said it had to do with the need for catharsis. Think Greek and Elizabethan tragedy, the gothic novel, melodramatic opera, and film noir. In the visual arts, the tradition goes back to the Middle Ages: paintings of dragons and other monsters, visions of hell and last judgments, beheadings, crucifixions, and other grisly martyrdoms.

But, where fear continues to be a dominant emotion in other art media, it petered out in the visual arts. When was the last time you left an art gallery in the wake of an adrenaline rush? Fear came to be something that was beneath art’s intellectual dignity. Leave the serial killers and the supernatural to the books and movies, seemed to be the thinking. And yet, well, something was lost. Fear is a fundamental human emotion. In surrendering its claim in that area, art risked becoming sterile.

The trick for today’s artists has been to rediscover fear, while adhering to modernist principles. Few wanted to go back to painting skeletons flogging naked souls in Hell.

The various ways this problem was resolved can be seen at “Danger,” an exhibit at Exit Art in Soho, which comes up with about two dozen artists who set out to startle, alarm, horrify, or frighten.

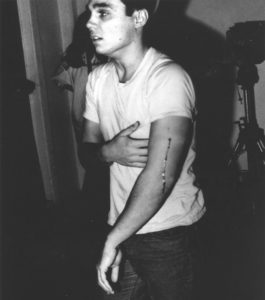

Chris Burden after being shot in the arm in 1971.

The most effective strategies fall into two categories. The first traces its lineage from Chris Burden, whose 1971 film “Shoot” became something of a performance art classic. The film, on continuous showing in the video portion of the exhibit, shows Burden being shot in the arm with a 22-caliber rifle. He flinches at the bullet’s impact – a flesh wound to the upper arm – then walks forward briskly, as if he had somewhere else to go. In an interview, Burden said he staged the event to interject some reality into a culture that viewed countless faked shootings in movies and on television. There’s a big difference, he emphasized, between a shootout on TV and “looking down at your own arm with a smoking hole in it.”

The piece made Burden famous, and he moved on to other extreme performances. He had himself nailed, crucifixion-like, to a Volkswagen, crawled naked through a pile of broken glass, and stuck himself in a locker for five days. Other stunts involved near drowning and electrocution.

As the exhibit demonstrates, Burden spawned a genre, albeit one that came to be dominated more by masochistic exhibitionism than deep evocations of fear. We see Mexican artist Ximena Cuevas applying a fresh serrano chile pepper to the rims of her eyes, as if it were eyeliner.

Slaven Tolj mixes vodka and whiskey in a gesture symbolic of globalization and the trauma of rapidly changing politics in Eastern Europe. A video shows him stoically downing the drinks until he passes out and has to be taken to St. Vincent’s Hospital.

With fireworks shooting out of the top of a metal helmet, David Hall, a Minnesota performance artist, transforms himself into a “living pyrotechnic” – a forgotten art form from the 16th and 17th centuries. Out in Los Angeles, Skip Arnold clung to the hood of a moving tractor trailer for a video titled “Hood Ornament.”

Burden was once derisively called “the Evel Knievel of contemporary art,” but artist David Leslie, the so-called “Impact Addict,” embraces the role in enthusiastic parodies, sparring with boxer Riddick Bowe, being pummeled and kicked by martial arts masters (while wearing a padded suit decorated with twinkly lights), and attempting to launch himself over a mountain of watermelons on a Soho street (he plunged head first onto the watermelons – but emerged from the wreckage with macho flair).

Our patience with these stunts does wear a bit thin as we watch the helicopter rescue of Allen Tombello, who had purposely stranded himself on the side of a mountain.

The other strain of scary art might be said to have evolved out of minimalism. In that style, artists strove for a geometric purity with simple forms, such as cubes or pyramids. Many of these pieces tended to be big and heavy, however, and were seen as threatening. Some artists capitalized on this, such as Richard Serra, who played with heavy slabs of iron and steel, tilting them at precarious angles. One such piece, in fact, crushed the leg of a worker who was helping to install it.

So, unlike scary movies and books, which act purely on the imagination, art could be scary by its mere physical presence, by its implied threat to the viewer. In this show, such works include those of Robert Chambers, whose sculptures have a menacing industrial character, with whirling blades and blaring horns.

Chico MacMurtrie’s robots are the most visually exciting pieces in the exhibit, although they are less scary than playful. Assembled from rusted rods, pipes, and metal discards, they are activated by computer and made to wave and jiggle and ejaculate steam in the direction of what is supposed to be a helpless female robot.

Artist Arnaldo Morales has the distinction of creating a work that was deemed too dangerous for “Danger.” His original piece consisted of two circular blades synchronized to just miss hitting each other as they spun above the viewers’ heads. Morales’ substitute work is a high-tech surgical-style instrument with a very nasty blade at one end and a pneumatic trigger-grip at the other. Visitors can squeeze it to produce a menacing vibration.

Other pieces in the show are more about danger than dangerous themselves. These include Keith Sanborn’s video installation, which makes use of the Zapruder film of the Kennedy assassination, and Susan Seubert’s photographs of things that correspond to various phobias: fear of beds (clinophobia), dolls (pediophobia), horses (equinophobia), snakes (ophidiophobia), and being tied up (merinthophobia).

Whether the artists here succeed in being dangerous or not, Exit Art deserves praise for putting together an exhibit that investigates a theme and allows for comparisons across various genres and artistic strategies. There’s too little of this in art nowadays. Artists and galleries are too often content to mystify, rather than putting their ideas to the test.

Exit Art gallery, NYC

2001