The exhibit, “Max Beckmann in New York,” might have been divined by a numerologist. Beckmann, the great German expressionist painter, died 66 years ago on the streets of New York. In late December of 1950, he was on his way from his Upper West Side apartment to the Metropolitan Museum, where his self-portrait was featured in a group show. He succumbed to a heart attack at the entrance to Central Park. He was 66 years old, a coincidence that might have interested the sometimes mystically-inclined painter.

Now the Metropolitan has borrowed that painting, a suave likeness of the artist in a blue dinner jacket, and made it the centerpiece of one of the best shows this year. It’s a relatively small exhibit — only some 40 works. It never quite lives up to its title, which suggests a rich and significant artistic relationship with a city that was his home for little more than a year, but makes up for it with a selection of earlier paintings that convey the full scope of his genius.

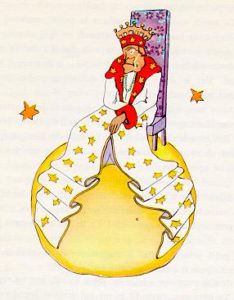

Beckmann was one of those modernist German painters whose works were declared “degenerate” by the Nazis. Stripped of his professorship in Frankfurt, he fled the Third Reich for Holland. This flight was prophetically evoked by his earlier triptych, “Departure,” in which scenes of horrific torture flank a center panel in which a royal family – a crowned king, his wife and child – sail away on a calm blue sea. He came to America after the war, and spent two years teaching in St. Louis before moving to New York in 1949.

After the placid Midwest, the city rejuvenated him. He described it, in a good way, as “a prewar Berlin multiplied a hundredfold.” His ramblings through Manhattan took him to honkytonk bars, past bowery flophouses, to the Latin Quarter nightclub and often included drinks at the elegant Plaza and St. Regis hotels – all places that provided him with the parade of characters that populate his pictures.

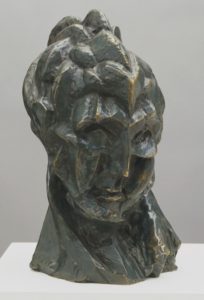

Photographs of him at his teaching job at the Brooklyn Museum Art School show a frumpy looking Beckmann in baggy slacks and a Ralph Cramden-like fedora clamped down on his head. It’s a far cry from the dandyish depictions in his self-portraits, in which he alternately looks a night club promoter, powerful industrialist, a yachtsman on the Italian Riviera and a spy in a trench coat. In all of these depictions, however, Beckmann’s powerful features shine through, a portrait of the artist as an unflinching observer and masterful creator.

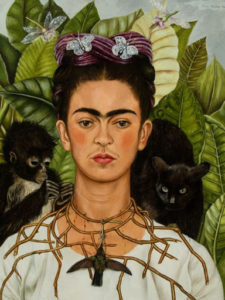

Beckmann, thank goodness, was no realist. His paintings are allegorical, filled with clowns, acrobats, soldiers, queens, and prostitutes. It’s not always clear what he was getting at. Why, for example, were women often rendered as masked giantesses, scantily-dressed Amazons with powerful shoulders and thighs like tree trunks? They are seductresses, yes, but they also look like they could break a man over their knees.

His wife, Quappi (Mathilde), in contrast, is usually the picture of gentle femininity, pretty and smartly dressed, and, as in Beckmann’s self-portraits, holding a cigarette between her fingers. She was 20 years younger than Beckman and lived on in New York after his passing, a promoter and interpreter of her husband’s work until her own death in 1986.

Beckman recognized that America was more puritanical than Europe and sometimes toned down his work to reflect this. The 1950 painting, “Woman with Mandolin in Yellow and Red,” was originally a treatment of the Leda-and-the-swan myth, in which Jupiter, in the guise of a swan, makes love to a young woman. To make it more acceptable here, he painted clothes on the voluptuous figure and, somewhat awkwardly turned the swan into a mandolin so that the reclining woman seems to be taking a break from her playing. Ironically, the work ended up in a German museum.

Probably the most famous of Beckmann’s New York paintings is “Falling Man,” in which an upside-down figure plummets to the ground amid burning skyscrapers. Of course, it would be impossible not to observe now that such imagery became a reality in Manhattan some 51 years later. But Beckmann’s widow denied that the picture was one of apocalypse, or even, as has often been assumed, a modern day image of Icarus, whose hubris made him soar too close to the sun.

Instead, she said, the painting’s meaning is to be found in the distant winged figures who float by in pink and green boats. They are angels and the falling figure is mortal man, flung down to earth and condemned to live there “with all its horrors and its beauties.” It’s not a bad description of Beckmann’s life and art. He embraced the full range of human existence. Heaven, for him, would have been unbearably dull.

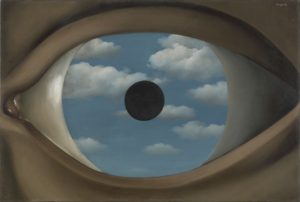

Let me tell you about this cool dream I had. These men were playing cricket in some sort of park, except the trees in the park looked like giant stair spindles. When the batter hit the ball, a giant sea turtle flew over his head. Except the turtle’s head was a smooth cylinder. And there was a woman in a box with a gag — or maybe a surgical mask–over her mouth…

Let me tell you about this cool dream I had. These men were playing cricket in some sort of park, except the trees in the park looked like giant stair spindles. When the batter hit the ball, a giant sea turtle flew over his head. Except the turtle’s head was a smooth cylinder. And there was a woman in a box with a gag — or maybe a surgical mask–over her mouth…