No one has ever known where to put Chaim Soutine (1893-1943). He is certainly an expressionist, but he doesn’t quite fit in with the German expressionists. His work has a childlike immediacy, but he was too well-schooled to be called a primitive. His energized, swirling brushwork has made him seem a precursor to abstract expressionism, and yet Soutine himself stopped short of pure abstraction.

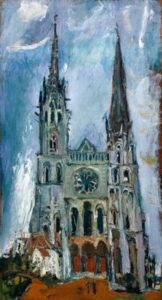

Soutine’s painting of Chartres Cathedral

In fact, one has to admire Soutine’s ability to frustrate the art historian’s efforts to pigeonhole him. Styles and movements have a way of smothering creativity. Soutine, who never signed a manifesto, had his hands full just being himself.

A Lithuanian Jew, he came to Paris in 1913, throwing himself into what was one of the most fertile and romantic artistic scenes in history. He lived the bohemian life, spent hours in the Louvre, and made friends among the other artists, including Amedeo Modigliani, who painted several portraits of him.

The last major Soutine show to be held in New York was in 1950 at the Museum of Modern Art. Now, the Jewish Museum has mounted a show of 56 paintings that focuses on Soutine’s career in Paris during the 1920s, his most productive years.

In his early still lifes, the artist’s loose and expressive brushwork is already in evidence, and the meager subjects – a few herring on a plate, or a couple of carrots – suggest the bare-bones bohemian life he was living.

From the beginning, too, we see Soutine’s unique approach to portraiture – a tendency to exaggerate the flaws and vulnerabilities of his subjects. His forlorn pastry chef and red-suited bellhops evoke compassion, even pity from the viewer, so sad and pathetic do they seem. In this heightened concern for their humanity, his portraits remind us of Van Gogh’s, though Soutine takes greater liberties with their physiognomy, affixing ears and noses with a seemingly perverse disregard for their proper placement, and pushing facial indentations to the point where the head looks like piece of clay that has been squeezed in a fist.

It is in landscape, however, that Soutine let it all go. In Van Gogh there’s always a sense of the energy in things, a visceral feeling of pushing and pulling; trees don’t just grow upward, they reach. In Soutine, we’re taken a step further. The world is not only alive, it’s in a state of emotional turmoil. The earth heaves, the air courses through the sky like rapids, trees seem to be tearing at their own foliage, and the neat lines of houses are distorted into strange geometries.

Chaim Soutine: “The Old Mill.”

His mildest landscapes have a cockeyed, fairy-tale charm; his boldest can give the viewer vertigo. Other artists were as free with color, but no one moved the paint like Soutine. As he developed his style, the paint seemed to go on faster and more furiously, the pigment palpably thick upon the surface, its oily texture retaining every subtle flick and turn of the brush, so that the viewer feels the presence of the painter’s hand.

In the early Twenties, Soutine began to short-circuit his landscapes, forgoing the description of things and building them with pure color. In “Hill at Ceret,” for example, all the colors of the hillside are there, the greens, the browns, the ochres, but they are only swaths of paint, layered and interlocked, like a pile of rags. Still, all the richness and complexity of the visible world is evident, and there is an appearance of drawing, as if things were being precisely rendered, even if the forms are unrecognizable. Thirty years later, Willem deKooning would do the same thing.

Abstraction was by no means a new idea in 1921. Cubism had run its course, and Kandinsky had created his “non-objective” style of painting that was analogous to music. But Soutine had gone far enough. For him, it had to be more than just paint and color and movement. He needed a picture. And so, in the later 1920s and 1930s, description flowed back into the paintings. In place of raw emotion, we encounter lyricism, a kind of childlike freshness, as in his earnest painting of Chartres Cathedral, where the usual maelstrom of brushstrokes is domesticated for the sake of architectural soundness.

Soutine is also somewhat notorious for his gruesome paintings of hanging chickens and bloody beef carcasses. This theme was apparently inspired by a Rembrandt painting in the Louvre entitled “The Slaughtered Ox.” The smaller animals, hung by their necks or their legs against backgrounds of icy blueness or black void, function as a stark symbol of death and mortality. But in the big carcasses, Soutine went beyond mere death and reveled in the gore and in the horror that this is what we are all made of. As with the landscapes, Soutine pushed these into abstraction, turning the red flesh, blood, gristle, and bone into fiery red compositions.

Soutine’s was a relatively brief career. He was catapulted to celebrity in 1922 when the eccentric American collector, Albert Barnes, purchased 52 of his works. As other collectors were drawn to his work, the critics began to argue over him, and haven’t stopped yet. In the 1930s, the view of his work changed radically from that of a mad primitive to a kind of traditional master, standing in opposition to the anti-painterly avant garde movements such as Dada and Surrealism. He died in 1943 of perforated ulcers.