“Agrarian Leader Zapata,”

There was no “Occupy Wall Street” movement when the Museum of Modern Art began planning an exhibit to commemorate the 80th anniversary of its Diego Rivera retrospective, and yet the timing now seems prescient. Who better to evoke the feelings of the dispossessed than the great Mexican muralist?

“Diego Rivera: Murals for the Museum of Modern Art” is a small, but unusual exhibit. The five central pieces are of a format – portable fresco murals – that was perfected for the original exhibit in 1931. There are interesting technical things to learn about this, but this is not nearly as interesting as the show’s story line, especially in light of the current dialogue about social class and power.

What seems so startling today is that an avowed communist artist whose work was not really very “modernist” would be given a show at MoMA and welcomed by the city’s upper-class cultural elite during the depths of the Great Depression.

A little background: Mexican muralism emerged in the 1920s in the wake of a bloody, decade-long revolution that brought a Marxist-dominated government to power. Under the direction of education minister José Vasconcelos, public buildings were adorned with murals that taught socialist ideals and celebrated Mexico’s pre-colonial indigenous culture.

The movement brought international fame to Rivera and its two other major figures: José Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros. In 1931, MoMA was a fledgling institution that had only given one other artist a one-person show – Henri Matisse. Matisse, of course, embodied the kind of art-for-art’s-sake aesthetic that MoMA was founded on and still represents today.

Rivera had been part of the Paris avant-garde in the early 20th century and was a cubist from 1913 to 1917. But his later mural style drew more on the frescoes of Renaissance Italy than on the examples of Picasso and Matisse.

They may have been propaganda, but in the hands of a genius like Rivera, they were also great art. The problem of how to do a show on site-specific works, was solved by having Rivera paint portable frescoes on steel-reinforced concrete-and-plaster panels. The first five he did are a kind of shorthand course in the Mexican struggle for liberation.

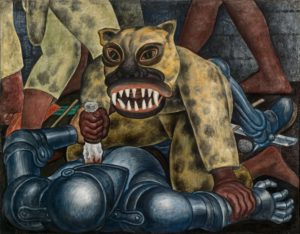

In “Indian Warrior,” an Aztec warrior wearing a jaguar costume stabs an armored conquistador in the throat with a stone knife. “Agrarian Leader Zapata,” an icon of the museum’s permanent collection, is a saint-like depiction of revolutionary Emiliano Zapata restraining a white horse, a dead landowner at his feet.

Two from this original group – “Sugar Cane,” which shows the abuse of farm laborers under colonial rule and the even-more searing “Liberation of the Peon,” which shows rebel soldiers cutting down a beaten laborer from a whipping post–are represented here by large drawings.

The last in this sequence, “The Uprising,” shows angry labor protesters clashing with soldiers in which the central figure is a mother with a baby on her hip.

After the opening, Rivera added three more murals that transferred the class-struggle narrative from Mexico to Depression-era New York. The most controversial of these, “Frozen Assets,” is a fanciful cross-sectional view of New York’s skyscrapers. Below the composite skyline can be seen an army of homeless construction workers sleeping on the floor of a warehouse, while below that, a woman sits in a bank vault inspecting the contents of her safe-deposit box.

Rivera and his wife Frieda Kahlo took New York City by storm. They were interviewed and feted everywhere they went. But there were obvious tensions in the communist artist’s relationship with the power elite, which came to a head in the notorious incident involving the mural he was commissioned to paint for Rockefeller Center in 1933.

Rivera ran afoul of the Rockefellers when he included the head of Vladimir Lenin in “Man at the Crossroads.” Among the memorabilia on view from this project is a letter from Nelson Rockefeller asking Rivera to paint out the image. He refused, and the mural was covered, then destroyed.

This didn’t stop the work of the Mexican muralists from having an enduring impact on American art. It became the chief inspiration for the Works Progress Administration (WPA) mural program that employed so many artists during the Depression.