Chances are you’ve never heard of the symbolist-expressionist painter Ferdinand Hodler. Partly that’s because he spent his career in Switzerland — a reasonable enough thing to do, given that he was Swiss – but history tends to favor those artists from major art centers.

Before you start thinking “minor,” however, imagine Hodler – whose works are at Neue Galerie – as a fine wine, kept out of sight in the cellar for all these many years and now uncorked for an audience who can appreciate it for the first time. It’s the opposite situation over at the Museum of Modern Art where Edvard Munch’s “The Scream” – an overexposed painting if there ever was one – is currently on loan and viewers have to cope with too much familiarity rather than too little.

Hodler, born in 1853, had a solid reputation in early 20th Century Europe. He exhibited in Paris, Berlin, Munich and other European cultural centers, but was most at home among the expressionist artists of the Vienna Secession, whose leading lights, Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele, praised his work and credited him as an influence.

In the company of those Neue Galerie demigods, Hodler can seem a bit conservative. You’ll find none of Schiele’s bold sexual themes, or Klimt’s decorative gold-leaf-and-mosaic passages.

Hodler was the opposite in temperament, more the hedgehog than the fox, enamored of strategies like repetition and theme-and-variation with which he hoped to get some sense of eternity into his work.

His “View to Infinity” is laid out like an ancient frieze. Five women are posed like modern dancers of the time (think Isadora Duncan), barefoot in floor-length free-flowing robes, arms extended so that their hands almost touch. You’re supposed to imagine their artsy chorus line continuing beyond the sides of the canvas into, as it were, Hodler’s “Infinity.”

This idea works better, I think, in his panoramic landscapes of the Swiss Alps. Here, he seems a Van Gogh expressionist, summoning up mountainous volumes with thrusting planes of ultramarine, laying down pastures and fields with swift strokes of ochre and green and dotting a ridge with grazing cattle. In most landscapes like this, the tops of the mountains are rendered palely insubstantial to show their greater distance. But Hodler sometimes does the reverse and puts a mist-filled ravine in the foreground, so that the abyss seems to be swallowing the substantial mountain behind it.

In his last two years, Hodler painted broad horizontal landscapes in which mountains, lakes and foreground shore are reduced to elegant horizontals that do seem to stretch into infinity. They are heartbreaking sunsets, rendered in just a few colors – lemon yellow skies against purplish mountain ranges, alpine lakes reflecting the sky. In some, a line of curvy-necked swans line the canvas’s bottom, looking like a caption in hieroglyphs.

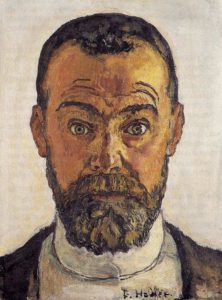

Hodler was at his most playful in his self-portraits. Photographs show that he usually painted himself looking younger than he was. He liked mugging it up, with eyebrows raised in mock surprise or eyes narrowed in the penetrating gaze of a hypnotist.

Hodler had an interesting personal life. He had several wives and several mistresses, all of whom he painted. The love of his life was Valentine Gode-Darel, with whom he had a child in 1913. That same year he and his wife, Berthe moved into an elegant apartment furnished by the famous Josef Hoffman, some pieces of which are exhibited in the show.

When Gode-Darel developed cancer, Hodler chronicled her two-year decline in painful series of paintings and drawings that seems part devotional act, part morbid compulsion. They fill an entire gallery, here. In the earliest, she holds their daughter Paulette on her lap. Gradually, she is shown becoming more emaciated, her head sinking back into the pillow, her arms growing thinner, her mouth gaping open, until you see her dead, laid out in her clothes, so skeletal that she looks seven feet tall.

Hodler died of a lung ailment three years later, in 1918, the year of the great influenza pandemic that claimed the lives of Klimt and Schiele. After Hodler’s death, his widow, Berthe, adopted the daughter he had had with Valentine.

Hodler’s reputation never flagged in Switzerland, but his paintings never became as well-known in this country as others from the Viennese Secession. This, the first New York museum show to focus on his late work, aims to remedy that somewhat.