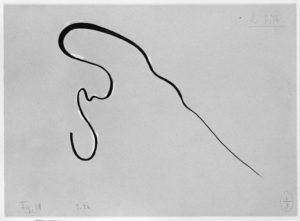

Vasily Kandinsky

You sometimes hear it said that drawing is on its way to being a lost art. Can that be true?

It is, if what you mean by drawing is the ability to gracefully and incisively translate three–dimensional reality into a two-dimensional image, if what you mean is the discipline that Rembrandt, Goya and Degas excelled at, that Van Gogh struggled so hard to master, that Leonardo daVinci said was the cornerstone of “learning how to see.”

That kind of skill is no longer the foundation of art school training. Young artists today are more likely to make their statements with photography, installation, performance, video, or even words, than with drawing.

And yet… it’s hard to let go of the idea that drawing matters. It seems so … fundamental.

With the exhibit, “On Line: Drawing Through the Twentieth Century,” the Museum of Modern Art makes the case that drawing didn’t die, it just got deconstructed. MoMA reaches back over a century of art and extracts the humble line – drawing’s basic element — and gives it what is surely its first solo show.

The result is a mixed bag. Trying to make an abstraction stand on its own can be interesting, but, well, the poor line has a hard time sustaining that interest over the show’s more than 300 works. The title, “On Line,” alludes to today’s high-tech connectedness, but it actually comes from the title of a 1920 essay by abstract painter Vasily Kandinsky. Kandinsky was a tireless systematizer and his analysis of lines finds such properties as temperature, movement, force, angle, sound and even male or female attributes.

The show gets off to a strong start. It begins in the second decade of the 20th century with some of modernism’s founding fathers, such as that lord of the lines, Picasso, and a black-and-white painting that looks like an elegant parts diagram for a disassembled guitar. Futurist Umberto Boccioni stirs up a storm of whirling lines in a trio of drawings that captures the dynamism of train travel.

El Lissitzky

Kazimir Malevich, whose suprematist style reduced everything to lines, bars, and squares, is a natural here. The same is true of his disciple, El Lissitzky, whose “Proun Room” ( a reconstruction), adds a third dimension to suprematist compositions so that lines pop off the wall like rods or thin boards.

Paul Klee, who once said “a line is a dot that went for a walk,” brings some lightheartedness to the discussion with such fanciful linear creations as “The Twittering Machine,” and “Portrait of an Equilibrist.” The show could have used a little more Alexander Calder, whose adventures in wire sculpture brought lines to hilarious life, but who is confined here to a couple of sober pieces that suggest orbiting planets and moons.

After mid-century, the show is much less rewarding. Jackson Pollock’s drip lines are a nice addition to the survey of line, but there are too many films and videos from the ‘60s and ‘70s of people drawing lines in snow, sand or lakebeds, or doing Zen-like things with string, rope and tape.

Contemporary art is represented by several site-specific pieces, such as Zilvinas Kempinas’s “Double O”, in which two strands of magnetic tape float in the wind of an industrial fan. Another is Luis Camnitzer’s “Two Parallel Lines,” which sends two knee-high lines along the bottom of gallery walls, one made of written phrases about line and the other a string of found detritus, like ribbon, tubing, cord, wire and yellow crime-scene tape.

You come out of this show seeing lines everywhere. Its most valuable lesson is that lines are mostly a human invention. They are the creation of artists, mapmakers and geometricians. As painter Edouard Manet once said, “There are no lines in nature, only areas of color one against another.” He might have overlooked the spider’s web and other filaments, but, then again, you don’t see those things in pre-impressionist paintings.