There are only a handful of serious painters who can be described as “funny.” Honore Daumier was one. Paul Klee was another. Then there is Lyonel Feininger.

Many people know the name, but not the work, which is understandable, since there hasn’t been a full-scale Feininger retrospective in this country in 45 years. Now, the Whitney Museum has mounted an excellent show that confirms what a funny and versatile artist Feininger was. What other serious artist can you name who also did a comic strip?

Feininger (1871-1956) spanned two cultures. Born and raised in New York City, he moved to Germany at age 16 to study the violin. Instead, he became a caricaturist and political cartoonist and eventually a member of the German-expressionist groups Die Brucke (The Bridge) and Die Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider). He was the first professor appointed at the Bauhaus – Germany’s influential school of modern design – at its founding in 1919. In the late 1930s, after a half-century in Germany, he fled the Nazis and came back to his native New York.

Although he’s often classified as a German artist, the Whitney claims him as an American, which makes perfect sense when you see his Chicago Tribune comic strips. What was more American than the funnies? “The Kin-der-Kids” and “Wee Willie Winkie’s World,” commanded full-page color spreads. Like Winsor McKay’s “Little Nemo” and George Herriman’s “Krazy Kat” a few years later, they were artsy and highbrow amusements – witty, but also sensitively drawn and colored.

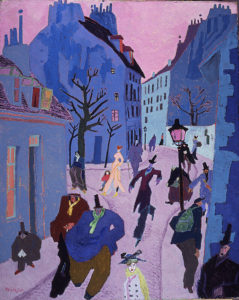

The strips were short lived, but Feininger brought the comics spirit with him when he began making real paintings in 1907. These folksy compositions of Old Worldish city streets are the first works you see in the show and they make an indelible impression. Seeing these, it’s easy to understand why many histories don’t even mention Feininger in connection with Die Brucke and Die Blaue Reiter. He took the same liberties with vivid color and primitive design as artists like Kandinsky, but left out the emotional tension and violent imagery.

One twilight painting shows Parisians strolling mauve streets past blue buildings. But the people look like cartoonish circus characters – the fat man, the midget, the man on stilts. Others are of bicycle riders, fishermen, trumpeters and street cleaners. In all, he plays games with scale, enlarging foreground figures into giants that span the height of the canvas.

Beginning in about 1919, Feininger’s compositions begin to acquire the sharp edges and angled planes of cubism. Marc Chagall made a similar blend of cubism and folkish fantasy, but with Feininger, the cubist system gradually pushed the fantasy out. In fact, it pushes the figures out of the picture, too, and the viewer is left with bare cityscapes marked by sharp shadows and beams of light. In the 1930s, the views are out over piers and shorelines. Feininger plays with the reflections and atmosphere of water in scenes of sunsets, storm clouds, sailboats, and steamer ships.

These can be lovely. But if you squint at some of them, the cubist details drop away, revealing a scene that can be disappointingly close to reality. A few paintings exhibit the old whimsy, as in a 1940 canvas of Manhattan at night, in which the cockeyed skyscrapers play the same jolly role as the odd-shaped people once did.

The playfulness that once went into the paintings was channeled into small painted woodcarvings of figures, trains, bridges and houses that he made from the 1920s into the 1940s as decorative amusements.

Painters, even funny ones, are entitled to conclude their careers with visions that are serene and ethereal And it’s hard to find fault with an artist like Feininger, who could do just about anything he wanted to do. In addition to being a painter, he was a skillful photographer and a musical composer.

But there were legions of cubists in the 20th century and few if any other painters who, like Feininger, could blend high art and low art – expressionism and caricature – into pictures that were both funny and beautiful.