In the last pairing of two great modernist artists, “Picasso and Braque: Pioneering Cubism,” Braque had described his partnership with Picasso as being like “two mountaineers roped to each other.”

Matisse’s “The Window” (1921).

Nobody ever said that about Matisse and Picasso. From the beginning, they were cast as opposites: Matisse, the rational Frenchman, the hedonistic colorist who once said art should be like “a comfortable chair”; and Picasso, the passionate Spaniard, the savage form-maker, for whom art was often more like an electric chair.

But here they are at the Museum of Modern Art in Queens, the two supposedly antagonistic lions of modernism, tethered together by intelligent curating, and practically purring in harmony. Well, not quite. The show doesn’t try to soften genuine differences, but it demonstrates through piece-by-piece pairings just how much these two innovators had in common, and how deeply aware and respectful they were of each other’s work.

“At times we were strangely in agreement,” Matisse once wrote.

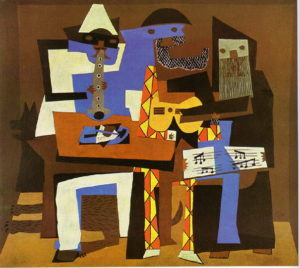

Picasso’s “Three Magicians,” also from 1921.

The exhibit succeeds on just about every count. In addition to abundant visual pleasures, it’s smart without being overly scholarly, complete (132 works) without being exhausting in scope, and has a great story. You leave this show as you might a satisfying play, in which the conflict between two brilliant men is set up and resolved through revelations of character.

The show opens with self-portraits that share odd affinities and role reversals. Both pictures were painted around 1906, the year the two artists were introduced by writer Gertrude Stein and her brother, Leo. Although Matisse later became known for his professorial formality — photographs often show him painting in a three-piece suit — here he looks quite bohemian, with beard and striped sailor shirt, and with a virile demeanor that we associate more with Picasso. Matisse was 37 and leader of the fauves (wild beasts), so called because of their unrestrained use of color. Picasso, beardless but with an identical hairline and an even looser-necked shirt, was 12 years younger, a difference made less significant by the fact that Matisse had been a late bloomer (he studied law before turning to art) and Picasso a prodigy, now beginning his meteoric ascent. Unlike Matisse, who stares out at us almost arrogantly, Picasso – usually the more confrontational —gazes intently at an unseen canvas, his painting arm displaying a Popeye-sized forearm.

Matisse was the more intellectual and articulate of the two. Picasso complained: “Matisse talks and talks. I can’t talk, so I just said ‘Oui, oui, oui.’ But it’s damned nonsense.” Picasso was more naturally the “wild beast.” So, it’s interesting to see that in this early period, Matisse showed more stylistic daring. His “La Luxe I” of 1907 is absolutely childlike in its simplicity. The nude figures are flat, just colored-in outlines. Picasso’s “Boy Leading a Horse” is much more conventionally rendered, but there is some tricky drawing in the boy’s body, so that we see different parts from slightly different angles, a device, learned from Cézanne, that was intended to counter the impression of three-dimensionality. Both painters had the same goal — a stronger flat composition, but Matisse simply takes the license, while Picasso carefully negotiates it.

In 1907, the two artists agreed to exchange paintings. Picasso took “Portrait of Marguerite” (1906), a painting of Matisse’s daughter. It looks more like a poster than a painting, charming and pretty, but as simple, almost, as a paper doll. Matisse chose Picasso’s “Pitcher, Bowl, and Lemon,” a claustrophobic cubist construction, in which the space is sliced up into colliding arcs and edges, shallow volumes and shards. There is a nasty story told that each artist chose a picture that would best illustrate the other’s weaknesses — and that Picasso’s cohort mocked and threw fake darts at the Matisse. But Picasso kept the painting throughout his life, and later spoke admiringly of its courage and spontaneity.

One of the most dramatic pairings is Picasso’s “Demoiselles d’Avignon” (1907) with Matisse’s “Bathers With a Turtle” (1908), pictures of comparable size, both of which appeared shockingly crude to audiences of the day. Picasso’s five nude figures seem distorted by a kaleidoscopic lens, and several faces inexplicably sport the features of African masks.

Matisse’s three awkward nudes seem even more determined to be ugly. The heads don’t fit well on the bodies, breasts seem unaffected by gravity, and one woman has a face like a Neanderthal. As with a study, Matisse doesn’t bother cleaning up places where changes have been made, leaving smudged corrections quite visible. The message seems to be that color is all, that this is primarily an abstract composition, not an illusionistic rendering of three people.

In contrast, Picasso builds architecturally, every line carefully engineered. The whole surface is tense with the interlocking forms. Despite the primitive masks, the savage distortions, there is nothing primitive or savage in the execution.

Despite the push into abstraction, neither Picasso nor Matisse made the whole trip. In his famous “Goldfish and Sculpture,” Matisse may not have wanted to give his goldfish fins or scales, but he still wanted them to be goldfish, still wanted that peg to hang it on, in the same way that Claude Debussy called a string of notes “Afternoon of a Faun.” Matisse evoked joy in his paintings, especially the circling dancers, but it was Picasso who had the sense of humor. It’s most evident in a painting like “Three Musicians,” in which the cubist reduction of form results in a trio of rectangular characters who look like they would be at home on “Sesame Street.” He could also endow ordinary objects with anthropomorphic qualities, as in “Still Life With Pitcher and Apples,” in which the shapely vessel with the mouth-like spout wears a plate of apples, the way women in later paintings would wear ornate hats.

Matisse’s reaction to cubism is an important subplot in the exhibit. Originally hostile to it, he later adopted some of its conventions, and even did one painting, “Still Life After Jan Davidsz de Heems ‘La Desserte'”(1915), that is clearly a tribute to Picasso and Braque’s system. Even in this one, however, the cubist tension from front to back is weak, and Matisse remained an orchestrator of two-dimensional compositions.

From time to time, both artists returned to realistic rendering, as to some temptation they could never quite give up, the sidewalk artist’s bread and butter. Picasso put a very realistic head on “Woman With Pitcher.” Matisse, in drawing “Lorette’s Sister,” seemed to get carried away with the particular construction of the woman’s nose.

For decades, critics used the Matisse-Picasso dichotomy as a pivot point for their reviews. It was useful to define one in opposition to the other. Matisse was “pure reason.” Picasso played “the game of a demon.” Matisse was of the French classic tradition, Picasso the restless romantic. Matisse painted from the object, Picasso from mood. Matisse was “sensual, an aphrodisiac” while Picasso wrestled with “metaphysical disquiet.” Matisse painted the exteriors of things, Picasso understood “their intimate structure.” Matisse was engaged with the personal drama of the artist, Picasso was engaged with the world.

In pushing each to the opposite pole, an aesthetic fiction evolved. This exhibit pulls both of them back toward the center. And, whatever their differences, there’s no question that their work is complementary. Take the Picassos out of this show and the Matisses would drop down a notch. And vice versa. Somehow, each makes the other look better. Why? Let’s leave it a mystery.

Museum of Modern Art, Long Island City, Queens

2003