The French artist Balthus, who died in 2001, is an unusual figure in 20th century art. He proved that a painter could work in the old-master tradition and still be unmistakably modern.

The French artist Balthus, who died in 2001, is an unusual figure in 20th century art. He proved that a painter could work in the old-master tradition and still be unmistakably modern.

At the same time, he raised eyebrows with paintings of girls in erotic and voyeuristic poses. Even in in our permissive culture, that is still a powerful taboo. Yet, there is nothing pornographic here. Sometimes the subjects are nude or partly so, but the mood is mostly psychological. They are early adolescents, somnambulant, dreamy, and awakening to their own sexuality – a legitimate artistic subject.

In a sign that some of the shock factor may be wearing off, the Metropolitan Museum has mounted a wonderful show playfully titled “Balthus: Cats and Girls — Paintings and Provocations.”

It draws on the early decades of the artist’s career, with 34 paintings from the mid-1930s to the 1950s. For Balthus fans, there’s a special treat in a suite of ink drawings made when the artist was a precocious 11-year-old. The 40 drawings, long thought lost, chronicle his adventures with a stray cat he called Mitsou.

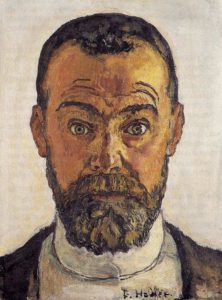

He was born Balthasar Klossowski in 1908. He grew up in Paris within a cultured and artistic family – his father was an art historian, his mother a painter. His mother’s lover was the great German poet Rene Rilke, who became a surrogate father to the budding artist after Balthus’s parents separated.

Like the masters of the past, Balthus wanted to paint the light streaming in the window, the blush and the roundness of a woman’s cheek, the mood of a cat. But to get attention in the 1930s, amid the surrealists and the expressionists, he had to be edgy, willing to push into secret pockets of human desire.

One gallery is devoted entirely to paintings of Therese Blanchard. She was 11 at the outset of the series, a serious-looking girl with chiseled features. By the time she is 13 she looks bored or moody, or is in some off-balance position that suggests the awkwardness of adolescence. In “Therese,” she is twisted around in a chair, legs crossed, like a woman in conversation at a cocktail party.

One gallery is devoted entirely to paintings of Therese Blanchard. She was 11 at the outset of the series, a serious-looking girl with chiseled features. By the time she is 13 she looks bored or moody, or is in some off-balance position that suggests the awkwardness of adolescence. In “Therese,” she is twisted around in a chair, legs crossed, like a woman in conversation at a cocktail party.

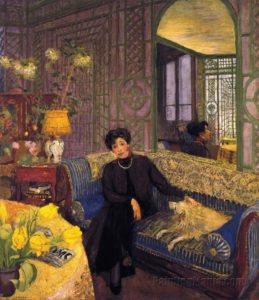

This is the birth of Balthus’s archetype, the child-woman. The nymphet in the “The Golden Days” looks like a character in a dream. She reclines on a chaise, her bodice slipping off one shoulder, her shapely legs exposed. Underscoring the mood of overheated passions is a man at the fireplace, stoking an already blazing fire.

The model for “Girl in Green and Red” was said to be Balthus’s wife, who was in her thirties, but looks about 15 years younger, here. She assumes the pose of a Tarot-card magician, a cape draped over one shoulder, an array of objects in front of her on the table, the painting imbued with an enticing sense of mystery.

And always the cats, peering out of the bottom or the corners of pictures with knowing or sphinxlike faces. In “The Game of Patience,” a girl leans intently over a game of solitaire while a cat beneath the table pokes at a ball with similar concentration.

Balthus identified with felines, titling his long-legged self-portrait “The King of Cats.” Later, in a fanciful painting made for a restaurant, he is a man-cat sitting down to eat a fish propelled onto his plate by a rainbow.

In “Nude with Cat,” a girl in a chair stretches back to play with a happy cat. The girl’s uncoiled body forms a diagonal that reaches nearly from one corner of the canvas to another. You know she will snap back in a moment. Balthus was brilliant at this kind of composition. He knew how to impart static scenes with a sense of movement and impending action.

There’s even pleasure to be had in the pebbly surfaces of Balthus’s paintings. The bumps along the contours of figures lend a tactile sense to the image – you can feel the artist dragging his brush along that curve again and again. The effect also makes the light in the pictures seem almost granular, a magical dusting along the edges of things.

Balthus stalked the viewer like a cat does its prey. He used everything at his disposal to draw the viewer in, to endow his paintings with beauty, mystery, and psychological depth. He was not so different from many other artists – or filmmakers, or writers – today who use sex to get attention. What made him different was that, beyond the sex, he had so many other gifts to offer.

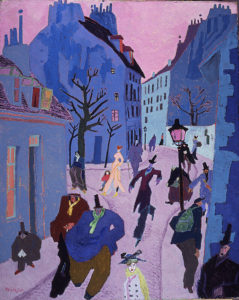

Color was always secondary in Picasso’s art. His radical reinventions of painting had to do with twisting forms, flattening space and rearranging people’s faces and limbs. “Color weakens,” he is reported to have said, which explains why such a competitive artist would have ceded that ground to colorists like Matisse and Chagall.

Color was always secondary in Picasso’s art. His radical reinventions of painting had to do with twisting forms, flattening space and rearranging people’s faces and limbs. “Color weakens,” he is reported to have said, which explains why such a competitive artist would have ceded that ground to colorists like Matisse and Chagall.