Need a cure for cultural overload? Worn out by mega-exhibits and museums the size of shopping malls? Relief can be found at Neue Galerie New York, a recent addition to Fifth Avenue’s Museum Mile.

Small, elegant, and aesthetically focused, it is the closest thing around to a perfect museum experience.

The art is early 20th century Austrian and German modernism – which sounds too narrow, but isn’t. It’s housed in a beaux-arts mansion that was once home to a Vanderbilt and looks it. It has a serious bookstore in what was once the house’s wood-paneled library and a restaurant that captures the style and ambience of the legendary Viennese cafes. It’s the kind of place where you can spend an hour or an afternoon and come away feeling alert and satisfied, as if you had visited someone’s private art collection.

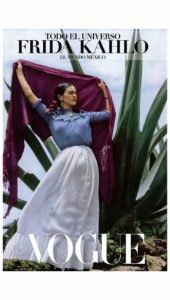

“Baroness Elisabeth Bachofen-Echt” by Gustav Klimt.

There’s very little wall text, no audio guides, no school groups, and no sense of a lock-step progression funneling you toward the gift shop. In short, none of the museum innovations of the past 20 years.

This charming museum with the old-fashioned outlook grew out of a friendship between the Viennese-born New York art dealer Serge Sabarsky and the philanthropist and art collector Ronald S. Lauder.

For years, they imagined a museum for Austrian and German expressionist art, Sabarsky’s specialty. In 1994, they found the building they were looking for, the six-story Louis XIII-style structure at Fifth and 86th, once the home of society doyenne Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt III. When Sabarsky died in 1996, Lauder went ahead with the project as a tribute to his friend.

The name is derived from Neue Galerie in Vienna, founded in 1923 by Otto Kallir as a showcase for the work of Gustav Klimt, Egon Schiele, and other luminaries of the avant-garde movement called the Viennese secession.

The inaugural exhibit, “New Worlds: German and Austrian Art, 1890-1940,” reflects what will be the permanent organization of the museum, with the second floor devoted to Viennese painting and decorative arts, and the third featuring such German movements as Die Brucke, Der Blaue Reiter, and the Bauhaus, as well as unaffiliated expressionists such as Max Beckmann.

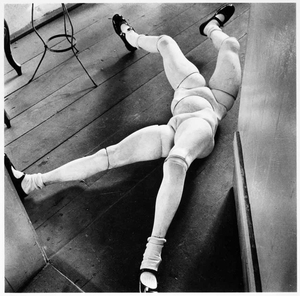

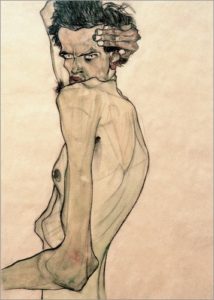

Egon Schiele “Self-Portrait.”

Turn-of-the-century Vienna was a magical place for art and ideas, part Babylon, part Athens. It had Klimt and Hoffman, Mahler and Schonberg, Freud and Wittgenstein. It was an affluent, prosperous place – the seat of the soon to be extinct Austro-Hungarian empire -a city enjoying guilty pleasures with a sense of impending doom. Countering this, idealistic avant-garde artists tried to forge a new culture. Viennese art has a reputation for decadence, for combining pleasure and pain, eroticism and morbidity, neurotic intensity and graphic sexuality.

The work of Schiele, in particular, crackles with erotic energy. One of the museum’s highlights is a half gallery of Schiele figure drawings, nudes in which the bodys’ skeletons look as if they’re trying to break out of the skin. Schiele was a virtuoso draftsman with a sinuous contour line that exaggerates every dip and declivity, every bulging tendon and tuck of flesh. His neurasthenic women sprawl languorously, embrace, or stare at their own bodies. Schiele—in a self portrait—twists pretzel-like, one arm around his head, eyes shooting lasers.

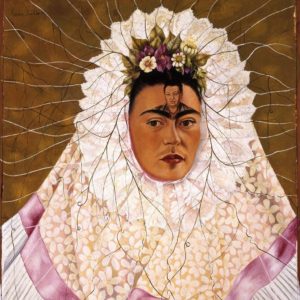

Klimt is easier on the eyes and nerves, though just as erotically charged. His art is more dream-like, more exotic, more Eastern. In his hands, the symbolist tendency toward decoration, toward mixing realistic passages with mosaic-like patterns, crosses into the realm of the psychedelic (which made his art a popular poster subject in the Sixties). He wraps his seminude figures in swirling patterns of colors, as in the portrait of Baroness Elisabeth Bachofen-Echt, who appears to wear a dress of silken luminescence, with a cape of floral and geometric forms that makes her look like a mysterious, gaily decorated Christmas tree.

The other big gun of this period was Oskar Kokoschka. His savage portraits of nervous intellectuals and neurotic society women seem barely there on the surface, like stretched paint rags scraped with the sharp end of a brush. But they have a telling, X-ray immediacy about them.

Kokoschka, by the way, outlived his two contemporaries by about 60 years. Klimt and Schiele both died in the influenza pandemic of 1918. Half the artists in this show, it seems, met early deaths from flu, war, or suicide.

Paralleling these radical experiments in painting was a decorative tradition that was no less daring. Even utilitarian objects took on eccentric forms, such as Kolomon Moser’s checkerboard chair with the lines of a shipping crate, or Otto Wagner’s minimalist stool with the curious slot in its seat. Josef Hoffman imparted geometric elegance to tableware, such as his octagonal serving dish, designed for the famous Cabaret Fledermaus.

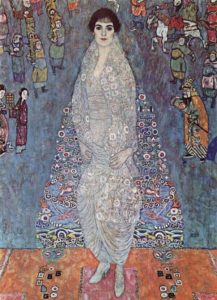

“Murnau: Street with Women” of 1908 by Wassily Kandinsky.

Upstairs, on the German floor, schools of art seem to multiply, with groups of three or four artists united in purpose by manifestoes, drawn up, one imagines, in smoke-filled cafes.

Der Blaue Reiter (“The Blue Rider”) group was named for a painting by Vasily Kandinsky. They rejected realism in favor of saturated and strongly contrasted color, as in Kandinsky’s street scene in which the red roofs of the houses look hot to the touch and the road is a high-keyed pink and yellow.

The hothouse appeal of Viennese decadence becomes something more malignant in Weimar Germany. The paintings of Erich Heckel and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner – part of a group called Die Brucke (“The Bridge”) – reveal a deeper pain and alienation. Kirchner’s tightrope walkers, painted with savage strokes and discordant colors, evoke the peril beneath the entertainment.

This lurking menace comes closer to the surface, and finally erupts full blown in the works of Otto Dix, George Grosz, and Max Beckmann. Grosz strips away the last veneer of romance with his painting of an ugly prostitute and her portly customer, while Dix give us a portrait of a distraught woman desperately trying to cover her sagging flesh.

The world of design, as exemplified in the Bauhaus gallery, moves on a separate track, maintaining the idealistic search for formal purity in the midst of social dissolution. Here can be found Mies van der Rohe’s slab-like Barcelona chair, and Marcel Breuer’s elaborately engineered Wassily chair with its geometric web of supporting straps.

Great care has been taken with the details in Neue Galerie. Despite the 18th century French design of the original mansion, the interior evokes the time and place of the art, with its black-and-white color schemes and bent wood furniture in the cafe. There’s even a design shop where you can buy jewelry, tableware, and bolts of cloth based on original designs by Hoffmann, Adolf Loos, Marianne Brandt, and others.

And, although the museum is the creation of a native New Yorker, not an outpost of the countries that produced the art, it has a certain air of Austrian formality and Germanic crispness. When you ask a question, you half expect one of the staff members to click his heels and give a sharp nod. And, despite being the baby of Museum Mile, it somehow projects venerability, as if this were a very old private museum that had just opened its doors to the public.

Neue Galerie

2002