One of the myths of modern art is that it left no room for narrative. In the beginning, that might have been true. Early cubist paintings, for example, rarely go beyond very simple landscape and still life. There’s no cubist version of “Leda and the Swan” or “Sermon on the Mount.”

And so, many artists took literally the idea of modern art’s revolutionary progress. There was no going back to those old storytelling pictures!

What, then, to make of Picasso, the co-inventor of cubism and one of modernism’s gods? As can be seen in the recently opened print exhibit, “Picasso: Themes and Variations” at the Museum of Modern Art, Picasso was very much a storyteller. He once called printmaking his way of “writing fiction.”

And what a cast of characters: nymphs, satyrs, sculptors, models, ancient Greeks, Biblical characters, wives, lovers, bulls, matadors, picadors and the artist’s most compelling alter-ego, the monstrous, lusty and ultimately tragic Minotaur.

Picasso made some 2,400 prints over the course of his career. The Modern, which has the country’s most comprehensive collection of this work, has selected about 100 of them for this gem of an exhibit.

As it happens, the exhibit is off the second-floor atrium, where the 64-year-old performance artist Marina Abramovic sits motionless at a table, a symbol of anti-narrative if there ever was one. This is part of her much hyped retrospective, “The Artist is Present.” Abramovic sits hour after hour, in one-on-one staring contests with a steady stream of visitors.

It is a famine for the eyes.

You can catch it without breaking stride on your way into Picasso, where the opposite experience awaits you. The earliest print in this show, “The Frugal Repast,” done in 1904 when the artist was 23, is a precocious masterpiece. The predicament of this gaunt and dreary couple, casualties of “La Boheme,” can be read in the gestures of their elongated and skeletal hands.

Picasso usually had the assistance of a master printmaker or two who coached him in the techniques of etching, drypoint, linoleum cut, aquatint and lithography and also did the actual printing. The exhibit is mostly in black and white, but there are splashes of color, as in the delicately tinted head of photographer-poet, Dora Maar, Picasso’s lover for nine years. In the 1959 linoleum cut, “Picador,” the actors are rendered in blood-red against a bright sun-yellow ground.

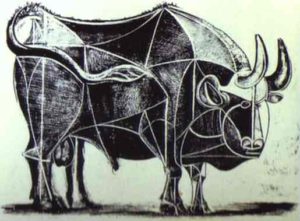

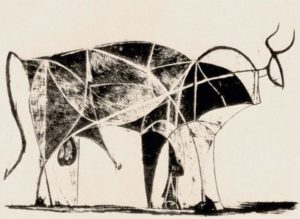

Picasso liked printmaking’s ability to capture a work’s evolutionary states, which allowed him to stop at any point along the way and make a print from a partially completed plate. Typically, these states acquire more depth and detail as they progress, but in a 1945 series of lithographs called “Bull,” the opposite happens.

After doing a rich and realistic rendering of the bull, Picasso surprised – and dismayed — the master lithographers by scraping the surface of the stone to erase – a no-no in the craft – what he had done. He then produced a series of progressively abstracted bulls using fewer and fewer lines. These went from segmented versions that look like butcher’s diagrams to the last, which is as simple as a wire sculpture.

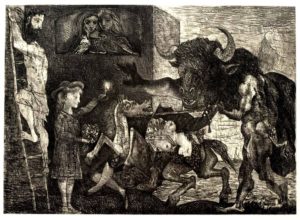

The most unforgettable character in Picasso’s “fictions” was the Minotaur, the subject of about a dozen prints, here. In mythology, the Minotaur was the monstrous and ferocious offspring of a liaison between Pasiphae, the wife of King Minos of Crete, and a beautiful bull. Picasso’s Minotaur is more cosmopolitan, sometimes merrily raising a champagne glass, other times jumping into orgiastic piles – once with a four-legged female centaur.

You can spend fifteen minutes studying the complicated “Minotauromachy,” which merges the Minotaur myth with the bullfight, but the most poignant pictures are those in which the blinded, bellowing Minotaur is led along a beach by a little girl. The pictures seem to draw on the story of Oedipus, the self-mutilated, inadvertently incestuous king who was led by his daughter, Antigone, in his final days. But the little girl in Picasso’s picture looks like his young lover, Marie-Therese Walter.

As biography, it’s indecipherable. But the themes and contrasts – monster and child, suffering and kindness, darkness and light, doom and redemption – are as rich as those in any myth, fairytale or Greek tragedy.

It’s also a far cry from the formal purity of modernism.