It’s fun to imagine the rejection letters that “The Little Prince” would probably get from publishers today. Children’s book editors would want to know what “age group” it was for. They’d almost certainly find it too moralistic and much, much too sad for children – especially the Little Prince’s death at the end. “Suicide by snake bite? Not for us!”

Defying conventional publishing wisdom, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s heartbreaking fable about an interplanetary traveler who is too pure of heart for this world, sells about a million copies every year – about 140 million in total since it came out in 1943. Written in French, and voted the best book of the 20th Century in France, it may come as a surprise to learn that “Le Petit Prince,” was actually written in New York City.

Not only that, but the original handwritten manuscript has never left Manhattan. Acquired by the Morgan Library in 1968 from an American friend of the author’s, it can be seen there now in an exhibit titled “The Little Prince: A New York Story.”

The show is proof that the book did not come easily to Saint-Exupéry. He was already a famous author by this time, having won America’s National Book Award in 1939 for “Wind, Sand and Stars,” a memoir of his flying experiences, but he had never done anything like this. He was more doodler than artist, and one of his recurring doodles was of a little man who sometimes had wings, sometimes stood on a little planet, and sometimes had thinning hair like the author. The character caught the eye of his publisher’s wife, Elizabeth Reynal, who suggested he make an illustrated book.

Saint-Exupéry had been a pilot in the French Air Force, but came to New York in 1940 with his wife, Consuelo, after France fell to the Nazis. They were welcomed by publishers, Eugene Reynal and Curtice Hitchcock, who helped set the couple up in an apartment on Central Park South. Depressed and anxious about his country’s occupation and his exile status, he threw himself into “The Little Prince,” often staying up into the wee hours drinking coffee, smoking cigarettes, and calling friends to read passages on the phone.

Saint-Exupéry also worked on the book in a townhouse on Beekman Place, a summer house in Asharoken on Long Island and at friends’ homes, including the Park Avenue apartment of Silvia Hamilton, whose black poodle served as the model for the story’s sheep.

You can see the coffee stains and cigarette burns on some of the pages put on view, as well as a once-crumpled-up watercolor that was rescued from the trash and flattened out. Fans of the book will find a great deal of new material, including early drafts, discarded scenes, preliminary sketches and unpublished watercolors. The original manuscript ran to 30,000 words but was eventually trimmed to less than half of that.

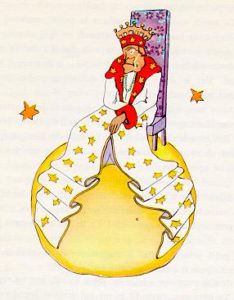

The story begins as the narrator, a pilot who has crashed in the desert (a real-life occurrence for Saint-Exupéry), is desperately trying to repair his plane. He is interrupted by the appearance of the alien traveler, who, in the book’s first turn of whimsy, asks him to draw a sheep. The elegant little prince wants a grazing animal for his tiny asteroid, which is constantly threatened by sprouts of baobab trees and where his only companion is a vain rose bush with a single flower.

The show has several drawings of the book’s most dramatic image, which shows what happens when the baobabs are allowed to get out of hand. At first, Saint-Exupéry, showed the tiny asteroid being devoured by the roots of one tree, but he eventually settled on the much better drawing with three.

In his writing, he was as meticulous as a poet, trying out about ten variations on the book’s central aphorism before settling on: “what is essential is invisible to the eye.”

Saint-Exupéry left New York in April 1943 to rejoin his reconnaissance unit in North Africa just as the first edition of “The Little Prince” hit the shelves of local bookstores. Before departing he stopped at the apartment of Silvia Hamilton and left a bag containing the material in this show, saying “I’d like to give you something splendid, but this is all I have.”

In July of 1944, he took off from Corsica on a solitary reconnaissance mission over the south of France. Like the little prince, who disappeared without a trace from the Sahara, Saint-Exupery never returned. His identity bracelet turned up in a fisherman’s net near Marseille in 1998. You can see it in the exhibit. It displays his name, his wife’s, and the lower Park Avenue address of his American publisher, Reynal & Hitchcock.