In 1902, Paul Gauguin, sick and impoverished in the Marquesas Islands, wrote a friend that he was thinking of returning to Europe to regain his health. His friend wrote back that it might be a mistake—now that he was a legend.

“You enjoy the same immunity as the great dead,” he wrote. “You have passed into the history of art.”

Even Gauguin’s most ordinary genre scenes from Polynesia have a meditative mood.

Within a year it was literally so. Gauguin, suffering from syphilis, painful eczema, and advanced heart disease, was dead. In the decade after, there were 46 exhibits of his work in 15 European cities. By the time of the famous 1913 Armory Show in Manhattan, Gauguin was a god of modernism. New York collectors snatched up his work. Many of these pieces eventually came to the Metropolitan Museum and many others have remained in private American collections.

“Gauguin in New York Collections: The Lure of the Exotic,” brings together 120 pieces—some friends, some strangers, and all of them revelatory. It doesn’t present itself as a blockbuster — the whole show fits in the lower level of the Robert Lehman Wing — and yet this show, rather than the more high-profile Thomas Eakins exhibit – is the true star of the summer season.

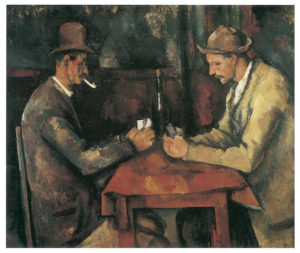

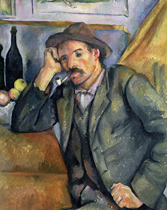

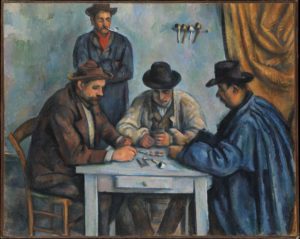

Mostly it’s because Gauguin, almost a century removed from us now, holds up so well. Much is made of his life in exotic locales, but the world revealed in the paintings is a timeless one of dreams and imagination. While Cezanne hammered out a new reality of structure, Gauguin— no less abstract—orchestrated his canvases like musical pieces, boldly simplifying shapes, finding new harmonies of hue in minor keys, and spraying notes of color across sun dappled clearings and swirling pools of water.

It just doesn’t get old, this kind of painting. Even now, after a century of artistic experimentation that he helped launch, Gauguin looks wiser and wiser. He knew the answer wasn’t in traditional realism or the optical realism of impressionism. Nor was in the reductionism that became the driving force in art after his death. Yes, painting should be abstract like music, he seemed to say, but it was also about the image, about drama, and the great stories of the past.

And, that is why, when he painted one of his Polynesian beauties, she often became Eve, or the Virgin Mary, or an Egyptian from the 18th Dynasty. And why, when he painted himself, he was Adam, or the devil, or even Christ on the cross.

Although many of the paintings in this show can be seen at the Met any day of the week, seeing them interspersed with works from upstate museums and private collections —including such masterpieces as the haunting “Manao Tupapau (Spirit of the Dead Watching),” and “The Yellow Christ,” both from the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo—makes them look new again.

Adding to the critical mass are eight Gauguins from a companion exhibit, “The Age of Impressionism: European Painting from the Ordrupgaard Collection, Copenhagen,” It includes his iconic work, “Human Miseries. The Wine Harvest,” in which a red-headed peasant woman, chin in hands, seethes with a kind of imploding fury—her face literally turning green in the process. She became a Gauguin archetype, a symbol of malignant unhappiness. She appears here in two different prints, a woodcut and a lithograph, both entitled “Human Misery.”

And that brings up another great feature of this exhibit, the cross-referencing between the major oils and the variety of other media that Gauguin worked in. You name it, he did it: sculpture, ceramics, wood reliefs, drawings, watercolors, prints. Indeed, Gauguin comes across as an artist-wizard who transforms everything he touches.

He could be an impractical a dreamer, but also tireless in promoting and explaining his art. He made a fictitious illustrated journal, “Noa Noa,” (Fragrance) about his first trip to Tahiti. He made suites of prints, gave interviews, and wrote long letters, often illustrated, in which he expounded on art and life and local politics. It didn’t bring him financial success, but his energy and versatility created a rich body of work in which images abound like leitmotifs in an opera.

Take, for example, his carving of a man with horns. The head is mounted on a pedestal, giving it the look of a quirky chess piece. It is another of Gauguin’s alter egos, but are we meant to see it as good or evil? Despite the horns, there is something benign and intelligent about this face. Elsewhere, in a pair of drawings titled “Polynesian Beauty and Evil Spirit,” the artist looks unrepentantly demonic. Man, he tells us, contains both Devil and God.

Gauguin explored man’s dual nature in this carving.

There are wonderful wood carvings here, including several large reliefs, and a wooden walking stick adorned with a with a naked Eve, an entwining snake, and a Breton shoe handle (which opens to reveal a secret compartment).

For all his immersion in primitive life, Gauguin sometimes painted from photographic sources, including documentary images and even Tahitian postcards. for some of his subjects. Equally clear, however, is how little it matters. Unlike Eakins, for whom the photographic reality was the goal, Gauguin used it as a starting point. Nothing is literally transcribed. In the case of the the Met’s own “Two Women,” from 1902, for example, which is based on an 1894 documentary photograph, nothing remains the same: not the poses, the landscape, the faces, or the color. Likewise for his famous painting, “Self-Portrait with Palette,” in which Gauguin wears a cape and a conical hat. It is based on a photograph. But in comparing the two —one prosaic, the other mythic—we experience the gulf between mundane reality and art.

Metropolitan Museum

June, 2002

With slow, methodical strokes, Paul Cezanne probed the secret structure of things. His subjects seem to tremble on a threshold – still the palpable apples, tables and trees of the natural world, but on the verge of dissolving into spheres, planes and cylinders.

With slow, methodical strokes, Paul Cezanne probed the secret structure of things. His subjects seem to tremble on a threshold – still the palpable apples, tables and trees of the natural world, but on the verge of dissolving into spheres, planes and cylinders.