With slow, methodical strokes, Paul Cezanne probed the secret structure of things. His subjects seem to tremble on a threshold – still the palpable apples, tables and trees of the natural world, but on the verge of dissolving into spheres, planes and cylinders.

With slow, methodical strokes, Paul Cezanne probed the secret structure of things. His subjects seem to tremble on a threshold – still the palpable apples, tables and trees of the natural world, but on the verge of dissolving into spheres, planes and cylinders.

The paintings are not so much about what you see, as about the sensation of seeing. The artist suppressed most traditional content –anecdote, narrative, physical likeness, and surface detail — in order to give a flickering glimpse of a more fundamental reality.

It was inevitable, I suppose, that some critics would find fault with this. Cezanne, some of them said, left too much out. His work is all about perception. It’s too cold, too analytical.

As one early-20h-century critic put it, Cezanne took “no more interest in a human face than in an apple… People and things impassioned him only with regard to their quality as objects to be painted.”

I’ve never bought it. To me, there is no lack of personal feeling, any more than there is in a poet’s description of aun unpeopled landscape.

But some people do, and the question is taken up in the Metropolitan Museum’s new exhibit, “Cézanne’s Card Players.”

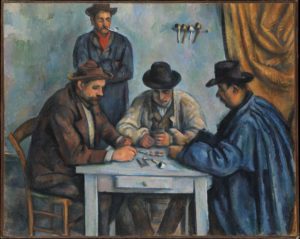

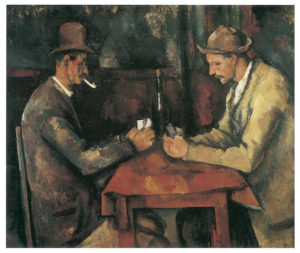

There’s never been a show devoted to this group of paintings. The complete card-player series consists of five big paintings – of which this show has three — and numerous studies and single figure portraits. All were painted between 1890 and 1896. Cezanne by this time had left Paris and the impressionist scene to live on his family’s estate outside Aix-en-Provence in the south of France. The subjects who posed for him were gardeners, other employees, and working people or “peasants.” In many, people smoke simple clay pipes or have them at hand.

Because these are genre pictures (depictions of human activities), people on both sides of the debate claim them to support their argument. Those who say Cezanne was emotionally engaged with his subjects point to these as belonging to a lively and colorful tradition of card-player paintings.

The show has two-dozen such works from the Met’s collection – mostly prints – that treat the motifs of card playing and smoking. These range from 17th-century Dutch and Flemish etchings and engravings to 19th-century French prints by Daumier and Manet. Many are rowdy scenes with drinking and gambling. In a print based on a Caravaggio painting, we see two card sharps in the act of cheating a foppish young man. The most memorable of these is 17th-century Flemish artist Adriaen Brouwer’s “The Smokers,” a tavern scene in which the artist himself gaily blows smoke rings, while another tipsy fellow blows smoke through one nostril.

But these paintings support the opposite argument as well. The images by the Flemish, Dutch and French artists are packed with personality and narrative. They could be scenes in a play, in which you can see frustration, triumph, concentration, and deviousness.

Compare this to Cezanne’s works, in which the card players sit stock still, seemingly studying their cards. There is no movement, no facial expression, no hint even as to the type of game or how it will turn out.

There is so little engagement between the players, that the art historian Meyer Shapiro described them as playing a game of “collective solitaire.”

And yet, what beautiful paintings. Cezanne, in making figures that seemed carved out of rock traded anecdote for a sense of timelessness. There’s something gained in these impassive demeanors that would be lost if one of them was smirking or steaming.

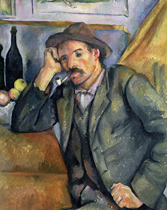

And it’s clear from his statements that Cezanne was very much concerned with the humanity of his subjects. At a time when his impressionist colleagues were painting Parisians with top hats and parasols, he saw his paintings as a tribute to rural traditions.

As he put it, “Today everything is changing, but not for me. I live in my hometown, and I rediscover the past in the faces of people my age. I love above all the appearance of people who have grown old without breaking with old customs.”

Such a figure can be seen in the portrait of a man who is believed to be of his gardener, Paulin Paulet, dressed in a suit and smoking a pipe. There’s even pathos to be found in the portrait of the slope-shouldered young man – titled “Peasant”– in which the subject stares downward in an attitude that seems to mix stoicism and defeat.