In 1963, when the “Mona Lisa” came to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the line stretched for blocks down Fifth Avenue; in less than a month, more than a million people filed past the portrait of the lady with the enigmatic smile.

The show of Leonardo da Vinci drawings at the Met is unlikely to excite such a fever, and yet, by rights, it should excite more.

“Study for an Angel,” by Leonardo da Vinci

Not to knock the “Mona Lisa,” but it’s a single painting by an artist who was not really known for his oil paintings. He completed only 15, whereas there are some 4,000 drawings. Most reside in Europe. But the Met, with loans from the Royal Library of Windsor Castle, the Musée du Louvre, and the Gallerie dell’ Accademia in Venice, has put together an exhibit of about 120 drawings for “Leonardo da Vinci, Master Draftsman.”

The art of drawing, like chess, ought to have a grandmaster status to separate Leonardo from the other gifted draftsmen of the Renaissance. For him, drawing was not just an aesthetic game, but a path to knowledge. He drew to understand how things worked. He drew as an aid to mechanical invention. He drew to create worlds of his own imagining.

He summed up his philosophy in the phrase “sapere vedere” (knowing how to see). Open your eyes, Leonardo tells us. You have only to see things properly to understand.

The exhibit is organized chronologically, with works from youth into old age, prefaced by a section on his teacher, Andrea de Verrocchio, and closing with works by Leonardo’s pupils and followers. There are studies for some of his most famous paintings, as well as celebrated anatomical and plant studies and designs for machines and weapons.

One of the chief pleasures of this exhibit is the insight you get into Leonardo’s eccentric personality He had a wandering mind, such that it might be argued that a facility for daydreaming was is a key to his particular genius. He could shift from contemplating the physics of light to plotting some practical joke involving stink balls made from fish guts. Toward the end of the exhibit is a page of cat sketches. Like a good artist-naturalist, he shows the animal in all its different aspects – sleeping, leaping, stalking, fighting, grooming – but in among them, not immediately noticed because of its feline pose, is a little catlike dragon.

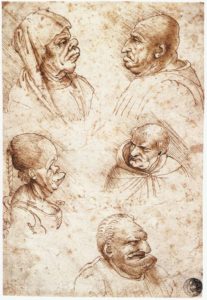

Five studies of grotesque heads by Leonardo da Vinci.

Contradictions abound. On the one hand, there’s the sober anatomist, whose innovative cross-section views of human skulls were centuries ahead of what medical science knew at the time. On the other hand, there’s the avid collector of “grotesques,” sketches of people with snub noses, beetling brows, simian muzzles, and other deformities, all rendered with a comical zeal.

Procrastinators can take heart in knowing that history’s greatest universal genius had trouble finishing things. Among the incomplete projects was the “Adoration of the Magi,” for which there are about a dozen studies in the show. The exhibit’s one painting, “St. Jerome Praying in the Wilderness,” is included here because Leonardo didn’t get much past the underdrawing. There are several pages of diagrams for an immense bronze horse for the Sforza family – illustrating innovative casting apparatus and furnaces – that never got off the ground.

Biographer Giorgio Vasari called Leonardo “capricious and unstable” and suggested that he conceived of problems that were “so subtle, so astonishing” that even he couldn’t solve them.

But could he ever draw. Precise in his scientific and anatomical work, he was equally comfortable in the poetic mode. Forms seem to coalesce on the page without the need for outlines. A head of the Virgin Mary – probably a study for the Louvre’s “Virgin and Child With Saint Anne,” is all sfumato – the soft merging of tone and shadow (literally “evaporating into smoke”) of which Leonardo was a master. The delicate shadows at the corners of the eyes and mouth – the same kind of shadows that confuse us about the Mona Lisa’s expression – give this face a benign but otherworldly expression.

Equally subtle and evocative is a tiny drawing, “A Copse of Trees Seen in Sunlight,” in which Leonardo wields red chalk with the delicacy of pen and ink, and ever so gently pulls leafy foliage out of the trees’ deep shade.

In other drawings you sense the artist reveling in the freedom of invention, snatching an idea from the imagination with swift strokes of the pen, as in “Rider on a Rearing Horse Fighting a Dragon.” In his “Leda and the Swan” sketches, Leonardo plumbs the myth for both its sensuality and its peculiarity. Jupiter as the swan is appropriately bold and sinuous, Leda clearly responsive, and then there are the consequences: Two large eggs from which have hatched four human infants who squirm and wiggle in the tall grass.

Although he professed to find war a “beastly madness,” Leonardo was quite willing to lend his powers of invention to weapon design. In a letter to the Duke of Milan, he described his skill as a builder of “very light and strong” bridges, “cannon, mortars, and light ordinance of very beautiful and useful shapes, quite different from those in common use,” and “armored cars, safe and unassailable.” His designs here range from arrays of various spearheads and fighting axes to an elaborate catapult with chains and gear wheels. In one drawing, we see men fleeing from a rolling shell or grenade that is spewing fire. Elsewhere archers shoot arrows through a shield attached to a bow.

The show ends with Leonardo’s apocryphal drawings of monstrous storms and deluges, end-of-the-world pictures in which the forces of nature sweep down with Old Testament fury on helpless cities and villages. What makes these drawings so powerful is that, despite their fancifulness, they employ all of Leonardo’s scientific knowledge about waves and air currents. Now writ large, the tidal waves and vortices seem all too real. And, well, Leonardo was prescient in so many ways — you can’t help but wonder.

Metropolitan Museum of Art

2003