Questions of authenticity and attribution were the kinds of issues that museums used to keep under wraps. Scholars might debate whether Rembrandt or one of his students did a particular portrait, but the visiting public got a much less ambiguous report.

Then someone realized that such stories had the appeal of a mystery. The stylistic features and mannerisms that could give away the authorship of a painting were like the clues Sherlock Holmes used to identify the murderer. And, the x-rays, pigment analyses, and carbon 14 dating were like the forensic analyses used on the CSI TV shows.

The trend has made for some fascinating exhibits, of which the latest is “Michelangelo’s First Painting,” at the Metropolitan Museum.

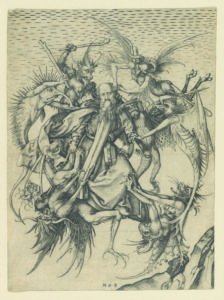

Can the juvenile hand of the artist many consider to have been the greatest of all time be discerned in a small oil entitled “The Torment of Saint Anthony”? Was this painting, a copy of a print by 15th century German artist Martin Schongauer, the one referred to in 16th century biographies of Michelangelo?

Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475-1564) was the epitome of the Renaissance man: poet, painter, sculptor, architect – even engineer. Although the frescos on the Sistine Chapel ceiling were one of his greatest accomplishments, Michelangelo considered painting a lesser art form than sculpture. Only three other easel paintings are attributed to him, two of which are unfinished.

The sleuth in this story is Met curator Keith Christiansen who had the opportunity to study the more than 500-year-old panel painting when it was recently cleaned in the Met’s conservation studios. The painting, which was always identified as being “from the studio of Ghirlandaio,” a Renaissance master, was bought at auction in London by the Kimbell Art Museum in Texas, where it will go after it leaves the Met in the fall. It is shown here with other, related paintings, including the Met’s portrait of Michelangelo by a follower, Daniele da Volterra.

The anecdote behind the show is one of those gems that biographers love to polish. The year was 1487 or 1488 and Michelangelo was 12 or 13. He had struck up a friendship with Francesco Granacci, who was about 19 and an assistant in the studio of Domenico Ghirlandaio (later Michelangelo’s master). Granacci, according to the story, gave Michelangelo the engraving by Schongauer as something he might use to practice painting, which he had never tried.

Print by Martin Schongauer,

The subject – a man encircled by monsters – is a fantastical image worthy of a Marvel comic. That’s part of the charm of the story – that this kind of weirdness is exactly the kind of subject you might expect a young adolescent, even a genius one, to be interested in. Saint Anthony floats in the air, his expression stoical, as the grotesque creatures do their best to drive him mad. Each is an assemblage of spare parts from all levels of the animal kingdom – the wings of a bat, the muzzle of a dog, the body of a fish, the tail of a reptile, the proboscis of an insect. They howl, bare their teeth, claw, tug at his robes and flail away with stick and torch.

The greatest challenge in making a painting from an engraving is in inventing the color. According to the biographers, Michelangelo went to the fish market to study the colors and the scales of the fish. This becomes one of Christiansen’s chief arguments in claiming the painting as one by Michelangelo: the painting’s fish-monster has scales, whereas the print’s does not.

Christiansen finds other evidence to support his attribution: a poorly rendered hand and other anatomical errors suggest a young and inexperienced artist, while certain improvements suggest the promise of genius. Schongauer’s engraving overflows with detail, but has no unity. The painting, in making the conglomeration of figures a solid dark form against a light sky, gives the figural mass a grotesque power even from a distance. This striving for monumentality was one of the hallmarks of Michelangelo’s career.

There is no jury in cases like this. Scholarly consensus is the closest thing to a verdict in the art world. That may take some time, but the Met’s Christainsen has put together a very compelling case.

.