If William Blake were alive today, they’d call him an “outsider artist.” That’s the 21st century name for painters who persist in painting their own mystical visions – in Blake’s case, sunburst angels, humanoid dragons, amorous tulips, dancing fairies, and whirlpools of humanity streaming through the cosmos.

The Londoners of the 18th and early 19th century were even less kind. They called him “poor Will,” and the man “who sees spirits and talks to angels.” One art critic described him as “an unfortunate lunatic” who’d have been locked up but for his “personal inoffensiveness.”

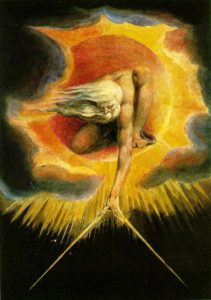

“The Ancient of Days Taking Measure of Time,” by William Blake.

But in the years after his death in 1827, the world began to change its mind about Blake. The pre-Raphaelite painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti was an early champion, as was William Butler Yeats. A Blake society sprang up in 1912, and the Bloomsbury crowd was wild for him. Gradually a Blake industry was born, attracting mystics, Jungians, hippies, and rebels.

His posthumous reputation, however, was based more on the poetry than the paintings. His images of naked spirits and bearded prophets have been viewed as “illustration,” something short of real art in the modernist system.

But now even this condemnation is giving way – as an exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art superbly demonstrates – to a view of Blake as a special kind of artistic genius who achieved the most original fusion of word and image since the illuminated manuscripts of the Middle Ages.

With about 180 works, the Met’s exhibit is a trimmed-down version of a mammoth exhibit shown earlier this season at London’s Tate Britain. It attempts to make Blake’s often obscure and personal mythology more comprehensible by placing it in the context of his time – a daunting job, since Blake’s art was meant to defy the confines of reason, and it embraces opposites: innocence and experience, lamb and tiger.

Born in 1757, Blake came of age in London during a period of political and social repression that followed the revolutions in France and America. He criticized the city’s pollution, the gap between rich and poor, and the “dark, satanic mills” that were sprouting up all over. “I wander thro’ each charter’d street,/Near where the charter’d Thames does flow./And in every face I meet/Marks of weakness, marks of woe,” he wrote in the poem “London.”

Many of Blake’s poems and pictures had political messages, but, as it became more dangerous to voice such ideas, he cloaked his themes in mythology and fantasy. His painting of the mad king Nebuchadnezzar, made by God to walk on all fours like an animal, may have covertly been an image of his own monarch, King George III, who suffered an episode of insanity.

He saw the battle of his time as one between the repressive forces of reason and those of imagination. One of his most famous images, the Ancient of Days taking measure of the cosmos with his compass, is often misinterpreted as a picture of a benign creator. In Blake’s cosmology, he is Urizen (a play on “your reason”), who destroys the imagination with his limiting measuring tool.

Likewise for the seemingly noble figure of Sir Isaac Newton hunched over his sums. The rock he is sitting on turns out to be at the bottom of the ocean, to which Blake wished to banish those who tried to explain the world with purely logical principles.

Blake was for ancient knowledge, spiritualism, and mysticism. His poems are mixtures of druidical, Swedenborgian, and occultist mythology. When he was about 10 he saw a tree filled with angels, the first of many such visions he would have. One of his most bizarre works, “Ghost of a Flea,” is a literal transcription of something Blake said he saw – the parasitical bug transformed into its true spiritual self, a scaly, bat-eared man-beast thrusting his tongue at a bowl of blood.

Often friendless and short of money, he was unsuccessful, depending on hack engraving jobs and occasional patrons. He had every reason to be despondent, but he never stopped writing charged, fervent poems, illustrating them, and printing them himself. The more of an outsider he became, the more grandiose his claims. He thought himself the equal of Raphael and Durer.

His main emotional support was his wife, Catherine. She worked with him on his engravings, stitched his clothes, cooked his meals, believed in his visions, and even learned to have visions of her own. There is a famous story of the two of them sitting naked in their garden and greeting a visitor with the remark that “it’s only Adam and Eve, you know.”

The show immerses the visitor in the Blakean mysteries, but also emphasizes the technical expertise and sheer grind involved in its production. A display of copper plates demonstrates the engraving technique he invented – relief etching – in which everything but his images and words was corroded from the plate.

Like other artists who wanted to reinject spirituality into a rapidly industrializing and materialistic world, Blake harked back to the religious Middle Ages, with its sinuous Gothic forms and illuminated manuscripts. He became expert at weaving text and image together, as can be seen in the opening of “Songs of Innocence,” where living tendrils wind around ballad-like verses and swoop upward to bring the eye up from the bottom of the page. In his “The Sick Rose,” the flower is painted in bruised red and murky greens, its stem curving downward to the heavy, unsupported blossom at the base of the page.

These books are to the visual arts what opera is to classical music, which is why it’s so silly to try to hold them up to separate literary and artistic standards.

He didn’t always hit the mark. His illustration for his famous “Tyger” poem shows a rather tame-looking pussycat of rainbow hues, rather than the burning presence we expect.

As this exhibit shows, Blake’s dreamy images were the product of a very particular time in history and a very unusual sensibility. He is one of those rare artists who creates his own world and requires the viewer to submerge in it entirely. “The Imagination is not a State,” he wrote, “it is the Human Existence itself.”

Metropolitan Museum of Art

2001