What accounts for the surge in popularity of “outsider art?” One answer is that contemporary art has starved people of sincere human expression. So, they turn to the work of religious visionaries, eccentrics, and psychotics, who—uncorrupted by art theory and fashion —create purely out of inner conviction.

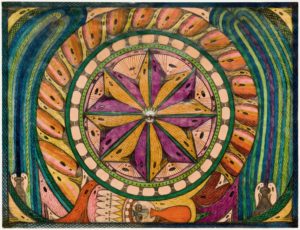

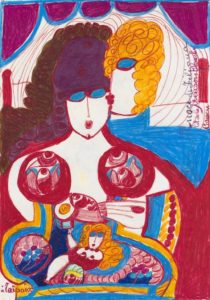

“Bangali Firework” (1926) by Adolf Wolfli

In embracing this work, however, the audience is faced with a new problem: dealing with whatever it is that made this artist an outsider in the first place. In some cases, the causes are only isolation or naïveté. But what if the artist is psychotic? What if it’s someone far outside the mainstream of ordinary human feeling and perception?

In his 1898 essay “What Is Art,” Leo Tolstoy said a genuine work of art should communicate an emotion and make a person feel “so united to the artist that he feels as if the work were his own and not just someone else’s.” Art’s chief appeal, he believed, was “freeing our personality from its separation and isolation” and “uniting it with others,” both the artist and the other people who respond to it.

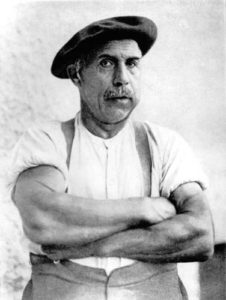

The art of Adolf Wolfli, on view at the American Folk Art Museum, puts these ideas to the test. Wolfli was born in 1864 and grew up in Bern, Switzerland. His father abandoned the family when Wolfli was 5, and his mother died three years later. Wolfli grew up as a hireling, with no permanent home. He excelled in school, but as an adult continued working as a farmhand and handyman. Between 1890 and 1895 he made several attempts to molest young girls. He served a prison term, and was ultimately sent to the Waldau Mental Asylum in Bern. There, he was diagnosed as schizophrenic and remained institutionalized for 35 years until his death in 1930.

Adolf Wolfli

Violent and agitated at first, he found his salvation in drawing. In 1902, one of his medical caretakers observed that Wolfli “had drawn very industriously for the entire summer.” The same report summed up his artistic efforts as “very stupid stuff, a chaotic jumble of notes, words, figures [to which he gives] fantastic names.” In 1907, a psychiatrist at Waldau, Dr. Walter Morgenthaler, took a different view. Psychiatry at the time was interested in art as a key – like dreams – to the human psyche. But Morgenthaler found aesthetic merit in Wolfli’s work as well, and in 1921 wrote a pioneering monograph on his life and work.

Morganthaler put Wolfli’s work in two groups: single-sheet drawings that he called “bread art,” because Wolfli traded them for things he wanted, such as art materials and tobacco. The rest belonged to a vast narrative cycle that combined prose, poetry, musical compositions, and illustrations. These were bound in 45 tabloid-size books and 16 smaller school notebooks that together contain an incredible 25,000 densely filled pages. They begin with an imaginary autobiography, “From the Cradle to the Grave.” In the next phase he expanded his life story into the realm of myth, with the “Geographic and Algebraic Books,” a narrative of fantastic travels and adventures throughout the universe. He then remakes the universe in his own image, calling it the “St. Adolf-Giant-Creation” – the title of the current exhibit.

The chief feature of Wolfli’s work is the incredibly dense patterning. Every drawing is packed border to border with detail, every area is subdivided again and again. Psychiatrists describe this as a horror vacui – the compulsion to fill in every square inch of an artistic surface. A number of pieces, for example, look like mandalas, which Swiss psychiatrist and theorist Carl Jung – who owned several Wolfli works – felt could be therapeutic for people in chaotic mental states. But, whatever drove him to obsessively make patterns, Wolfli became a master at it.

Wolfli’s drawings – in both plain and colored pencils – are at once very, very strange, yet oddly familiar. They remind you of the ornate borders and elaborately decorated letters of medieval illuminated manuscripts. Sometimes you see Oriental rugs, tarot cards, tapestries, Persian miniatures, a child’s board game, a primitive map, diagrams from biology, and paper money. Some are mostly abstract, and look like a swirling paisley, or a mysterious engineering diagram. Various motifs show up repeatedly, such as teardrop or capsule forms, and ribbon-like bands that unfurl across the surface, themselves filled with circular or oblong beads, musical notes, writing, or faces. Many of these seem animated – the blips and beads seem to move in their channels like the lights on a Broadway theater marquee, or a Times Square sign.

Many have symbols and things in them: townscapes and castles, boats and trains, birds and trees, as well as angels, smokestacks, fences, and bells. In almost all of them you will find a little moonish face looking out. Some are in circular frames, like the portraits on paper money. They have moustaches, elephant ears, horns, a black mask, and most frequently, a cross coming out of the top of the head, like an antenna. They are cartoonish faces, and there’s something a little creepy about them, the lack of expression, their enigmatic presence.

After his death, Wolfli’s work came to the attention of Jean Dubuffet, founder of art brut, a style that embraced the art of children, the naïve, and the mentally ill. Dubuffet called him “The Great Wolfli.” Another fan was Andre Breton, leader of the surrealists, who were particularly interested in psychotic states,- who valued the unconscious mind and anyone – such as the mentally ill – thought to have greater access to it.

Drawing becomes less important in Wolfli’s late works. In so-called “number pictures,” he calculates his fictitious wealth up to the year 2000. Subsequent series includes “Books With Songs and Dances” (1917-22), and “Funeral March,” in which music is the primary means of expression. When images are called for he begins to use magazine illustrations.

In his writings and lists of “inventions,” you are made more aware of the gulf between sense and nonsense, between the coherent and incoherent mind than in the drawings, which depend less on logic and rationality.

Not that there aren’t frustrations here, as well. As different as the drawings are, they are also relentlessly alike. They are systems or visions for which we have no key, for which there likely is no key. For all their complexity, energy, and apparent richness, they are locked doors. Like schizophrenic speech, they flee from sense into the safety of incoherence.

But we are nevertheless richer for having seen them. Which brings us back to Tolstoy’s definition. We don’t really receive a particular feeling from Wolfli; few people will recognize their own thoughts, here, or feel united with the artist. But we gain a window into another kind of consciousness – a mind pumped full of pressure, intense and disjointed. We step into a long dream, take joyless flights of fancy, and know the irresistable compulsions of the psychotic.

The American Folk Art Museum

2003

The 75 works in the show, some from as far back as the 1700s, range from images of trumpeting angels to multiheaded beasts, from city plans of the heavenly New Jerusalem to chronological charts of history’s progress in millennialist terms.

The 75 works in the show, some from as far back as the 1700s, range from images of trumpeting angels to multiheaded beasts, from city plans of the heavenly New Jerusalem to chronological charts of history’s progress in millennialist terms.