How to account for Ralph Fasanella? A labor organizer and social activist, he showed no signs of artistic talent or even interest through early adulthood. Then, in the summer of 1944, he went on vacation in New Hampshire with a group of friends, one of whom was an artist. Fasanella saw her sketching and tried it himself. He drew a rowboat, a pair of shoes, and the inside and outside of one of the cabins. The results were surprisingly good.

An explosion of drawings followed.

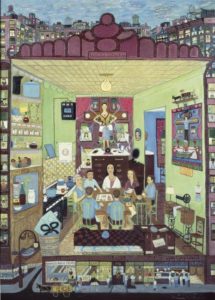

“Family Supper” by Ralph Fasanella.

“When I became an artist, all of a sudden every fiber within me was alive,” he recalled years later. “My body was constantly excited, intoxicated with wonderful feelings of joy. Ideas came out. I couldn’t sleep.”

Fasanella, 31 years old, never looked back. Soon he was using oil paints and pouring all his life experiences into panoramic canvases: the New York City neighborhoods he loved, subway cars, machine shops, baseball stadiums, parades, and labor strikes.

He got attention here and there from shows at union halls and small galleries, but real recognition didn’t come until 1972, when New York magazine ran a cover story with a photo of a smiling Fasanella surrounded by his canvases. “This man pumps gas in the Bronx for a living,” the headline read. “He may also be the best primitive painter since Grandma Moses.”

Nothing was the same after that: a coffee-table book, an uptown exhibit, a PBS profile, and enough sales to get him and his family out of the Bronx and into a house in Westchester.

Now, the whole span of Fasanella’s career, from those early drawings done in 1944 right through to the last paintings before his death in 1997—a career spanning 52 years—can be seen in a major retrospective, “Ralph Fasanella’s America,” at the New-York Historical Society.

The comparison with Grandma Moses was both apt and not so. The two late-blooming artists (Grandma Moses was an even later bloomer, not starting until her 70s) share a similar flat, patterned style and a fondness for the big picture, a way of looking down on the world from a godlike perspective, with multitudes of human figures reduced to tiny scale. Fasanella evoked the complexities of urban life in the 1930s, just as Grandma Moses evoked the pastoral joys of her New England girlhood. But Fasanella differed from Moses in having a social program.

An ardent reformer, who, in Heminwayesque fashion, had gone to Spain to fight fascism in the Thirties, Fasanella continued to promote his utopian vision through his paintings. His first major canvas, “May Day,” portrays one of the huge labor parades that were once held in Manhattan’s Union Square. We see the parade marching through the downtown streets, the blocks packed with spectators. The painting lacks sophistication: The people are simple doll-like figures, the linear perspective shifts from one building to the next, and there is a complete absence of aerial perspective (the fading of things in the distance). But, despite the primitivism, this is far from childish. Fasanella organizes and unifies the sprawling composition by consolidating small elements into larger, boldly defined shapes. And, it doesn’t detract from his accomplishment to point out that this painting resembles a giant board game, with the ribbon of an elevated highway snaking around the perimeter of the scene and parks, gardens, and tenements as stops along the way.

Pictures of Fasanella at work show him using small brushes. If he painted a stadium full of people, there is no shorthand, no impressionistic treatment to suggest a large crowd. He paints every figure in the grandstands, each head dotted with a crop of hair, each torso with two arms and two parallel legs. Paintings made up of so many little pieces of color might fall apart in a cloud of confetti, but, once again, he pulls it all together, either by making a big abstract shape – a baseball stadium turns into a giant pinwheel – or by giving each painting a particular cast, as in “Grove Street Interior,” in which color is skewed toward the greenish side of the spectrum.

Fasnella’s paintings have a way of going on and on: another block, another tenement, another park with children playing. This is never more true than in “New York City,” a 110-inch-wide triptych that is one of Fasanella’s masterpieces.

In the foreground is a neighborhood scene that represents a condensed stretch of upper Broadway, Fasanella’s stomping grounds. The center of the painting is dominated by the 59th Street Bridge. Its sweeping curves carry the eye out to Queens and suburban Long Island beyond. The painting also manages to gather together the elements of the New York skyline – the Empire State Building, the Chrysler Building, the Brooklyn Bridge.

His overtly political paintings can become too symbol-laden and diagrammatic. His paintings about the executions of the Rosenbergs, the Kennedy assassination, and the social upheaval of the Sixties seem not so much pictures as propagandistic lessons, blueprints to change the world. More successful is the series on the 1912 “Bread and Roses” strike in Lawrence, Mass., in which he adopted a rigorous realism. He studied and absorbed every detail of the industrial environment, learning what machines did and how they worked before attempting to paint them. In some, he used cutaway views to peek into entire floors from the outside. In others, he uses colors expressionistically: A red-brick mill set against a fiery red sky, its chimney blasting out gas and sparks, evokes a labor situation that has reached the boiling point.

The Lawrence paintings were the crowning achievement of Fasanella’s career. By the 1980s, his intensity had begun to wane. The same sentiments are there, as in the rendering of the New York Daily News strike, but the energy needed to orchestrate big, detailed compositions is not. He could still be charming, as in his fey rendering of Times Square— a New Yorker cover for the Broadway Jubilee issue in May of 1993—but charm is not the quality we associate with Fasanella.

Fasanella’s art has been described as the visual equivalent of street talk – direct, opinionated, improvisational, and passionate. But without the social convictions, his art would have had no purpose. His paintings championed working class culture, and the dignity of labor. He always remained a Thirties leftist, tough and big-hearted, continuing to insist that America live up to its ideals as a humane, democratic society.

New-York Historical Society

2002