His world is one of awesome scale and frightening artificiality: hotel atriums that seem to soar into infinity, and massive office buildings, viewed at night, in which workers look as trapped as battery-reared chickens. Or a midnight rave where a sea of young bodies wave their collective arms like the cilia of some huge organism.

It’s the futuristic yet contemporary vision of German photographer Andreas Gursky, a rising star in the art world, with a bold claim on the 21st century zeitgeist, which, in case you haven’t guessed, is the phenomenon known as globalization.

Gursky makes bigger photographs than you’ve probably ever seen, both in their actual size and in the amount of space they seem to contain. And, he is global in his locations: Atlanta, Paris, Hong Kong, New York, Shanghai, Cairo, Salerno.

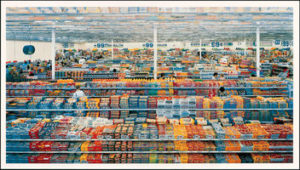

He has favorite motifs, such as the floors of stock exchanges, where traders swarm like panicked ants. The ants are black and white in Tokyo, red and white in Hong Kong, and every kind of color in Chicago. He is drawn to the anonymous, gridded facades of huge buildings. And he embraces the world of consumer goods, whether row upon row of gaudily wrapped gum and candy in a 99-cent store, or Nike sneakers reverently arrayed in softly lit museum-like displays.

His immense color photographs – some as long as 16 feet – can be seen at the Museum of Modern Art. The 46-year-old photographer’s background is equal parts German academic avant-garde and slick commercial photography. Some of what he does is not that different from corporate annual report work, where industrial subjects are cleverly shot so as to capture an appealing abstract design. Think aerial views of highway cloverleafs.

The difference is in scale and intent. Most of his photographs easily fill your entire field of vision, and the color can be lush and seductive. Those of natural landscapes – the forbidding gray-and-silvery zone of an alpine glacier – have a grandeur akin to Hudson River School painting or German romanticism. But, usually his aesthetic mix is more complicated. There’s grandeur, but it’s artificial, man-made grandeur.

Humanity, meanwhile, is reduced to an anonymous herd. There are no individuals in Gursky’s photographs, and no real human emotions on display – unless you count the mass psychology of the mega-sporting event or rock concert. The energy and movement you see is that of a colony, a collective, faceless entity. And what does this burgeoning consumer colony feed on? Mass-produced goods. Shiny electronics, things with logos on them.

Gursky’s view of Salerno, Italy, is a stunning panorama of a harbor totally dominated by man-made structures. Almost every surface has been paved over to accommodate commerce. Containers are stacked as high as small buildings, and new cars and trucks are lined up by the thousands. Cargo ships load and unload with the aid of cranes. In the background, high-rise buildings march up the ancient hills like an advancing army.

The thing is, it isn’t an ugly picture. The mountains, the ships, the colorful containers all combine into a strong composition. Even more striking is the way every part of the picture is in sharp focus. Everywhere you look, except the distant mountains, there is crisp detail.

Gursky also has a penchant for art historical games and references. A photograph of one of Jackson Pollock’s abstractions seems to ask, can a photograph of an artwork be an artwork? Another is a close-up of some brushstrokes from an unspecified painting, so you don’t know what you’re looking at, Lady Hathaway’s coiffure or the fur of her dog.

With certain kinds of images – such as highways and rivers – Gursky tries to reduce to semi-abstract stripes that invite comparisons with color field paintings. Gursky’s version of the classic monochromatic canvas? A photograph of gray carpeting.

But, it is the convergence of these two impulses – the documentary and the art historical referencing – that gets Gursky into trouble.

The problems stem from his decision, in the Nineties, to alter his pictures with digital manipulation. In the beginning, he confined himself to editing out unwanted details in the service of clearer abstract statements. But, as he continued to play with symmetries and repetitions, he began to make more radical changes. His weird view of the atrium at the Times Square Marriott Marquis hotel, for example, are really shots of different facades that have been combined to create an enclosure that doesn’t exist. He rearranged the walls of the Hong Kong stock exchange to create another fictitious space.

Both of these photos have a documentary character. They contribute to Gursky’s overall narrative about our impersonal, globalized world. His changes don’t just make for a neater, more interesting abstraction, but exaggerate the dehumanizing quality of these contemporary scenes and places, giving them a stranger, sci-fi appearance.

These issues are addressed, but not really resolved, in the catalog essay by curator Peter Galassi. In essence, he argues that the ability to manipulate photos or to create photo-like images will eventually undermine the whole notion of documentary truth. A new generation will approach photographs without our hangups about factual representation, he suggests. And besides, he says, photographs were never really truthful to begin with.

On some level, that may be true, and there’s no question that photographers in the past made alterations. Edward Steichen and other turn-of-the-century pictorialist photographers altered gum negatives with brushes, giving them a painterly quality. But this was for poetic effect. These were photographic fantasies and didn’t purport to show real places.

Gursky’s work can have a stunning visual impact. And it feels like now. But as you catch on to what he’s doing, an uneasiness creeps in, which isn’t helped by such non-explanatory titles as “Atlanta” and “Times Square.” These pictures’ claim on our imaginations stems from what they purport to tell us about our world. Frankly, if we lived in the world that Galassi foresees, in which photographs are routinely suspect, we’d find them much less interesting.

Museum of Modern Art

2001