“Visions From America” at the Whitney Museum, a survey of about 60 years of photography from the museum’s collection, has a funny hitch about halfway through. Around the mid-1970s, much of it stops being about photography.

Yes, they’re still photographs, but they no longer speak for themselves. You feel like you need a program to figure them out. Why is that illuminated light bulb sitting in that glass of water? What’s with the big camera with the pair of legs? And that fake setup of robins with the mystical circle of eggs?

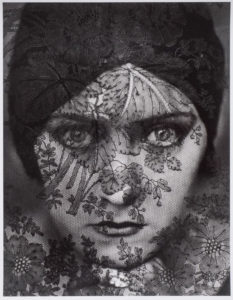

Joel-Peter Witkin, “Face of a Woman.”

These are photographs in the service of ideas, ideas that are more important to the meaning of the works than the medium. And yet, that revelation by itself is worth the price of admission, because it tells you how much art and photography have changed roles in the past 25 years.

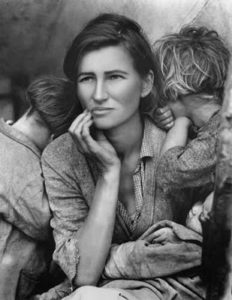

In the Forties and Fifties, photography had its own territory and values. Slice-of-life photographers such as Robert Frank moved into the gap left by the move of artists into abstraction. Photography still sat lower on the aesthetic ladder, and much of it was indistinguishable from the kind of thing seen in Life magazine, but it was a poetry of the real: pedestrian herds on Fifth Avenue, train commuters enveloped in their newspapers, glittering theaters on 42nd Street, a tangle of teenagers at Coney Island.

Some of it was socially conscious, the dark side of the “Family of Man,” with a focus on the poor and the outcasts: black transvestites outside the 1963 opening of “Cleopatra,” a group of retarded children in a playground, an illiterate scrawl on a tenement wall (“A decetive lives here”).

Another, more aesthetically minded group, which included Minor White, turned away from the social scene and looked so close at blotches of tar or a shadow on a sidewalk that the images became near abstract.

Then, with pop art, the line between art and photography was blurred. Andy Warhol and Robert Rauschenberg silk-screened photographs onto canvas. The subjects, even when painted, were often drawn from commercial photography — billboards, tabloid sensationalism, newspaper ads.

From then on, the idea of two tracks for art and photography was finished. Conceptual artists, such as John Baldessari, combined photographs and words to pose philosophical conundrums. Other artists used photographs to record works that weren’t accessible to the viewer, such as Robert Smithson with his “Spiral Jetty.” Still others toyed with the relationship between artist and model by making nude photographs of themselves, such as Adrian Piper and the corpulent John Coplans.

Others subverted the idea of photography as a mirror on the world by photographing fabricated scenes. Cindy Sherman made mock movie stills starring herself in different guises. William Wegman took mock serious portraits of his Weimaraners.

The show is also a reminder that the culture wars of the late-Eighties and Nineties probably wouldn’t have happened without the ascendancy of photography. Would there really have been such a fuss if Robert Mapplethorpe had been a painter? Andres Serrano, notorious for submerging a crucifix in a jar of urine, is represented here by what looks like a twisting beam of light, clarified by the title, “Untitled X (Ejaculate in Trajectory).” Joel-Peter Witkin, the most gruesome of the death-and-body-part-obsessed photographers, contributes his infamous “Man Without a Head” (1993). This is no sideshow fake, but something out of a morgue, a decapitated body propped on a stool, ludicrously attired in black socks, its neck a gaping wound.

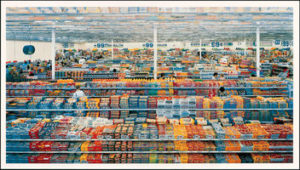

One of the ironies of the ascendancy of photography in art has been the growing conviction by some artists that photography — at least the commercial kind — has become a monster. According to this thinking, we are so inundated with images from advertising, movies, and video that no one really knows what’s real anymore. We are submerged in a simulated reality. These artists try to comment on this image-world phenomena by using — what else? — photography. Barbara Kruger makes satirical in-your-face advertisements, or, as here, a “Thinking of You” greeting card with a picture of a safety pin being jabbed into a finger.

And, now, all this reality business has been taken a step further by the digital altering of images by computers. At least one image here, a bleakly empty office lobby, has no basis in reality at all, although it looks plausible enough.

Looking at all this idea-based photography, much of it now detached in time from the zeitgeists of 15 or 20 years ago, it’s sometimes hard to remember what it was supposed to be all about. You have to work too hard to remind yourself why Coplans photographing his body from so many odd angles ever seemed like a good idea. Likewise for Sherman’s porno-horror grotesque with rubber breasts and gleaming razor teeth.

All this is not to say that photography has been completely subsumed by art theory. Along the way, some people have kept to the old ways of doing things.

It’s nice to see that someone is still photographing abandoned motels along deserted highways, or some hollow-eyed hard-luck family in a rundown car, or an interesting tangle of tree branches in some remote landscape.

But the big news, though hardly a surprise, is that photography — not painting, not sculpture — has become the common language of art.

Whitney Museum of American Art

2002