Should a war painting be beautiful? You can’t help wondering that at the Metropolitan Museum’s exhibit of Civil War paintings where history plays in the shadow of awe-inspiring landscapes.

“The Civil War and American Art” joins a show on Civil War photography that opened at the Met earlier this spring. Both are occasioned by the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg (July 1-3, 1863), the turning point of the war.

But whereas the mid-19th-century photographs document a bleak and tragic panorama – corpse-littered battlefields, burned-out cities, amputees – the paintings employ the vocabulary of the Hudson River School of painting – misty valleys, stunning vistas, dramatic skies.

Take Albert Bierstadt’s “Guerrilla War” of 1863, in which Union soldiers are shown firing down on Confederate troops from a stand of trees. You see the sparks flying out of the rifle barrels and the tiny figures falling from their horses. Then as your eye goes into the distance, you see the whole setup, the long train of confederate troops marching up the winding yellow road into the ambush. But instead of keeping your eye on the plot, Bierstadt takes you farther off into the hazy distance across a vast expanse of lovely country. Far, far away you see a church steeple and a column of smoke. The aftermath of a previous a battle? Perhaps. But it seems unimportant in such a beautiful scene.

Bierstadt and other Hudson River School painters broke new ground by evoking the grand, the sublime and the spiritual in the American landscape. When war came along they wanted to respond, but weren’t about to paint heroic scenes with rearing horses and raised swords.

The unprecedented slaughter of the Civil War was better captured by photography, which could unflinchingly show the bloated bodies heaped in ditches, as you can see in one section of this show, as well as in the galleries of “Photography and the American Civil War” on the Met’s main floor.

The pantheists of the Hudson River painters had a more difficult task in trying to use landscape, rather than traditional storytelling, to communicate the gravity of war.

Martin Johnson Heade successfully used weather as a metaphor in “Approaching Thunderstorm,” an ominous picture in which black clouds advance on a quiet cove still bathed in sunlight. A man and his dog watch passively, as if unaware that the storm is bearing down on them, but the little sailboat – the ship of state? – is too far from shore to avoid the storm’s coming fury.

This was 1859, two years before the war. In the summer of 1860, the skies offered up their own portents, with two months of meteor showers over eastern America. One particularly spectacular meteor was captured by painter Frederic Edwin Church as it broke into two fiery globes on the night of July 20th, 1860.

One of the most lyrical of the Hudson River painters, Sanford Gifford, served in the Union army. His canvases poetically reflect the everyday reality of war – the marches, the bivouacs, the campfires, Sunday services, the loneliness of guard duty. In “The Camp of the Seventh Regiment near Frederick, Maryland,” the sun breaks through the clouds as the regiment dries out its sodden gear, their mood lifted by news of the Union victory at Gettysburg.

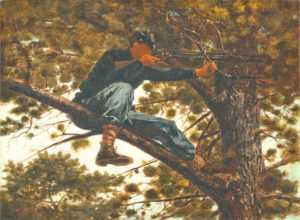

Winslow Homer worked as an artist correspondent for Harper’s Weekly and his paintings handle the action of war in a more straightforward way. His image of a Union sharpshooter braced in a tree captured a new reality of modern warfare – that rifles with telescopic sights could pick off enemies from more than a mile away. In a painting that beautifully captures the human response to this murderous technology, a Confederate soldier dances atop a rampart, defying the sharpshooters to hit him.

Slavery, of course, was the root cause of the war, and northern artist Eastman Johnson dramatized this in his “A Ride for Liberty—The Fugitive Slaves, March 2, 1862,” in which a father, wife and son ride one galloping horse for the Union lines, silhouetted against the setting sun.

The show is about the twilight of the heroic tradition in history painting. Next was World War I, which would be filled with so much mechanized carnage that only the unflinching camera could record it. The artists, shell-shocked, declared the world insane with a style of mock babbling called Dada.