Photography was only about 20 years old in 1861. By that time, the daguerreotype, tintype and even the 3-D stereopticon had found a place in American popular culture. People who could never have afforded a painted likeness could now walk into a storefront studio and come out with an excellent photographic one. It was a wonderful, entertaining, and democratic art form.

Photography was only about 20 years old in 1861. By that time, the daguerreotype, tintype and even the 3-D stereopticon had found a place in American popular culture. People who could never have afforded a painted likeness could now walk into a storefront studio and come out with an excellent photographic one. It was a wonderful, entertaining, and democratic art form.

Then the Civil War broke out.

In this tragic conflict, the deadliest in American history, photography found a monumental subject. Photography’s grim realism changed people’s perception of war. In the process, it transformed itself as well, from an entertainment into a serious medium. Photojournalism was born.

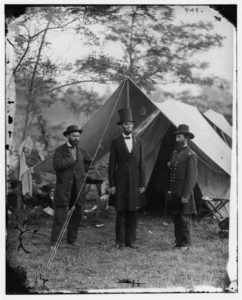

Now, in an exhibit timed to coincide with the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg, the Metropolitan Museum has drawn on its own extensive holdings of Civil War images to mount “Photography and the American Civil War.” The show opens a window into history while also showing how the war changed photography itself. The gallery walls are draped with white linen to evoke the tenting of the war’s encampments.

If there’s one photographer people associate with the Civil War, it’s Mathew Brady. It was Brady who made the famous portraits of Lincoln, in which, year by year, the president’s increasingly worn and grooved face seemed to map the war’s terrible toll. Brady is also known for his graphic pictures of the battlefield dead, grotesquely swollen corpses with blackened faces and gaping mouths that so shocked viewers at the time.

However, the focus on Brady as the great Civil War photographer can make it seem as if he was practically alone out there,

which was far from true. Brady, in fact, was more of an administrator than the man behind the camera. He orchestrated a corps of some 300 assistants, who were themselves only about a third of the total number there. All told, a thousand or so war photographers took hundreds of thousands of images.

The cameras were cumbersome, but the greater limitation was their slow speed. An exposure took up to 15 seconds. Attempts to photograph battles in progress resulted in nothing but ghostly blurs. So there is a bias toward portraits and aftermath scenes in Civil War photography.

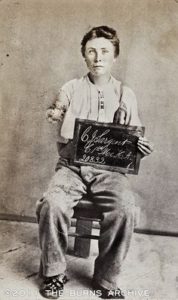

One of the first things a newly enlisted soldier did after getting his uniform was to have his picture taken. So the many portraits here – small tintypes or ambrotypes encased in metal frames – are the faces of yet-to-be-tested combatants who still believe in the glories of war. Brothers sometimes had their pictures taken together, as in the case of two confederate soldiers from a Georgia regiment shown drawing their swords from their sheaths.

Contrast these with the horrific medical photographs near show’s end of gangrenous limbs, emaciated torsos, amputations and unusual bullet wounds. These were taken by Dr. Reed Brockway Bontecou, a Civil War surgeon, for teaching purposes, but tell a more human story here.

The Civil War was one of the first industrial wars in which machines played a major role. The photographers enthusiastically documented all of this equipment, from a wagon carrying telegraph-line batteries to massive 13-inch mortar cannons to armored steamships. Some photos testify to the skill of army engineers charged with quickly erecting wooden railroad bridges to substitute for those blown up by enemy forces.

Some photographers made annotated albums, such as George N. Barnard’s “Photographic Views of Sherman’s Campaign,” which followed General William Tecumseh Sherman’s “March to the Sea” from Tennessee to Georgia in 1864 and 1865. His photographs of the ruins of Charleston, South Carolina show it reduced to rubble, as desolate as the bombed-out cities of World War II.

The Lincoln assassination and its aftermath dominate the end of the exhibit. Here, too, photography had a special role to play, as can be seen in the first photographically illustrated “wanted” poster, a printed broadside with affixed photographic portraits that led to the capture of John Wilkes Booth and other conspirators.