Never did a NYC MetroCard machine look like such a brilliant design. It had no attitude or cutting-edge aspirations. It stood solidly, with its big, colorful buttons, amidst the beeping, clicking high-tech confusion that is “Talk to Me: Design and the Communication between People and Objects” at the Museum of Modern Art.

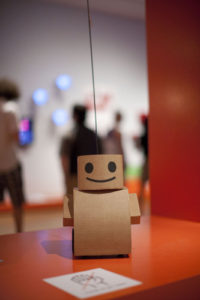

Down at my feet, a little cardboard robot was looking for directions. Shrill laughter issued from an adjacent gallery where a child was tickling a giant version of Talking Carl, a boxy iPhone app. Faces on the wall smiled with grotesquely enlarged mouths.

I wanted to hug the humble MetroCard machine. Someone put money in it and it responded faithfully. Click, click, click and the thin gold-and-blue card dropped silently into the pickup slot. Here, at least, was a form of human-object communication that was straightforward and useful.

Perhaps I’m not tech-savvy enough. Or lack the proper irony. But I rarely had the sense that the world needed most of the 200 or so things on display in “Talk to Me.” Superfluity is not usually a hallmark of good design.

So abandon all preconceptions, ye who enter here.

The idea behind this show is that contemporary design is no longer about what you see in MoMA’s Design Store, such as the Ray and Charles Eames chair with the potato chip seat or the Isamu Noguchi beehive table lamp. Those are objects that solve their utilitarian tasks with elegance and originality.

Now, in the digital age, objects aren’t even necessarily objects, anymore. Their existence can be purely electronic. But they have personalities, or at least simulate them and have become, as the catalog tells us, “very communicative.”

The exhibit loves cute animated creatures like Talking Carl and Tweenbot, the little cardboard robot. These are the pet rocks of the computer age, some virtual, some actual. The lanky rabbit called Mr. Smilt, for example, is a computerized stuffed animal. It is programmed to cry in response to a child’s cry, with the idea that the child will stop crying and instead comfort the animal.

Bug Plugs are power-saving electrical hubs in the form of plump, antennaed creatures that turn electronic devices on or off, depending on whether it detects a human presence in the room.

Once you endow objects with personalities, there will inevitably be malcontents. “TV Predator,” for example, is a picture frame that is jealous of the attention paid to nearby televisions and causes them to malfunction.

This, like many other things in the show, seems less an example of design than a work of conceptual art or a practical joke (the two are often indistinguishable).

Another item for the joke-shop shelf is the “Communication Prosthesis,” a pair of red plastic lip-inserts that pry open the mouths of the shy or socially awkward. It’s supposed to make them feel more outgoing, except that the teeth-exposing grimace it produces is about as charming as the face of Batman’s nemesis, The Joker.

Things get even more bizarre with “Call Me, Choke Me,” a collar that tightens around the neck of the wearer every time he or she gets a cell-phone call, a design for people who are into erotic asphyxiation.

Mixed in with the outlandish are a few solid inventions, such as EyeWriter, a collaboration from the Ebeling Group, the Not Impossible Foundation and Graffiti Research Lab. It was created for Tony “Tempt” Quan, an L.A.-based graffiti artist whose paralysis left only his eyes mobile. It uses eye-tracking glasses and a computer program to translate eye movements into lines on a screen. In Quan’s case, the graffiti tags he designed were projected onto the tops of city buildings, allowing him to continue practicing his art.

But the more you look in this exhibit, the more oddball things jump out at you, such as the “Menstruation Machine,” a metal device shaped like a chastity belt that simulates the experience of menstruation – including blood and cramps. It’s for curious men, presumably, but in truth, like many things here, it’s for an art school audience or exhibits like this one, where there’s a premium on creativity at its most perverse, and – unlike the MetroCard Machine — no expectation that it will ever actually be used by anyone.