With Sigmund Freud’s dream theory recently aroused from slumber by scientific research, a show on dream imagery at the Equitable Gallery seems particularly well-timed. Freud, who called dreams “the royal road to the unconscious,” is something of a muse for the 50 or so artists here who, in one way or another, have tried to evoke the bizarre, scary, and sometimes nonsensical subjects of those nightly newsreels.

Not that the father of psychoanalysis necessarily would have been pleased to see his book, “The Interpretation of Dreams,” at the center of this exhibit, “Dreams 1900-2000: Science, Art and the Unconscious Mind.”Art that capitalized on the novel imagery of dreams without supplying the context – who dreamed it and why – held no interest for him. Artists might be fascinated by floating eyeballs and the like, but Freud considered that material superficial, valuable only as clues to unconscious conflicts and wishes.

One painting that might interest him here was made by a patient, Sergei Pankejeff, known in Freudian literature as “The Wolf Man.” The dream, of seeing white wolves in a tree, was interpreted by Freud, through a chain of associations, to be about the childhood experience of seeing his parents having intercourse. The naively executed painting was made many years after his analysis. The same subject is better treated in an etching by Jim Dine that conveys – through flashing eyes and teeth, the dark interior of the tree, the violent motions of bodies and branches – the Freudian meaning of the dream.

Of course, dreamlike imagery predates Freud – the hellish visions of Bosch, or any number of mythological scenes come to mind. It could even be argued that all painting, as a melding of reality and imagination, is essentially dream-like in character. But many artists, the surrealists in particular, were directly inspired by the Viennese doctor’s theories. To them, dreams were the royal road to creativity.

The pictures in this show, organized by the art museum of the State University of New York at Binghamton, mostly fall into two groups. Some are like still shots from an actual dream. Others loosely use the language and the effects of dreams for a broader, surreal effect.

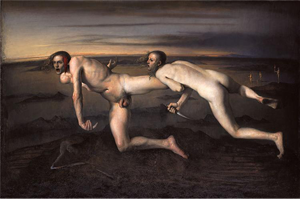

The contemporary Norwegian artist Odd Nerdrum, for example, takes us right into a nightmare – frightening for its utter realism – in which a knife-wielding woman pursues a man through the air. His head is already bloodied, and the title “Woman Killing an Injured Man,” leaves no doubt as to the outcome. Both figures are nude, and their bodies have the postures of sleeping people – the man’s arms and shoulders are twisted at an uncomfortable angle. The painting works like a dream, with its dark, primeval landscape, the strange lack of malice in the woman’s expression, and in the sexual suggestiveness derived from the placement of the man’s genitals at the center of the composition.

Nerdrum’s painting looks like a dream, with the Freudian stuff pretty close to the surface. It’s less successful in a purely artistic way, reminding us that perhaps Freud was right, that real dreams are raw material to be deciphered, too personal to strike a universal chord. Everyone has had the experience of

Woman Killing an Injured Man by Odd Nerdrum.

suppressing yawns while being told a long, complicated dream that the teller finds utterly fascinating.

Some dreams are universal, such as ones about flying or falling, or showing up in public naked. The poor fellow in Rainer Fetting’s “Dream x 76” is a picture of tragic helplessness, as he plummets, naked, through a skyscraper canyon.

In Seiji Togo’s “Surrealistic Stroll,” a white figure with a single black boot and black glove leaps as high as the rooftops, reaching for the crescent moon. Freud, according to the wall text, believed that flying dreams replayed the childhood experience of being lifted high in the air. As to meaning, it was thought to be sexual, at least for men, and accounted for why a male dreamer would report being “very proud of his powers of flight.”

William Baziotes’ abstraction with its embryonic forms manages to evoke those amorphous dreams that are recalled more as feelings than images. The symbols and totemic forms that tumbled out of Jackson Pollock’s mind onto paper have a similar impact, and, were in fact, midwifed by a Jungian psychoanalyst.

The flamboyant Salvador Dali, whose landscapes of melting clocks and swarming ants seemed to agree with so many people’s ideas of what a dream should look like, is here represented by a didactic painting called “Morphological Echo,” in which he demonstrates his ability at free association. A sequence of objects hovers above a table, each one relating to the next: a spoon in a glass echoes a walking woman who echoes a stone tower and so on. Dali found himself so susceptible to seeing one thing in another that he called his style “paranoic.”

Film is probably the best medium for reproducing dreams, and the exhibit has some excellent clips from those by Hitchcock, Bernardo Bertolucci, Luis Bunuel, Ingmar Bergman, and others. Bergman is quoted as saying that he sometimes transferred dreams to film exactly as he had dreamed them.

The prevailing theories about dreams have progressed from the ancients’ belief that they prophesied events to come, to Freud’s theory that the unconscious spoke through strange metaphors, to the hard-headed scientific idea that dreams are merely random firings of neurons to today’s notion that finds these neuron-firings to be more Freudian than random.

We live in an age when no common, living mythology offers itself as a natural vehicle for otherworldly narratives. Dreams have filled that gap for some, though the personal nature of the imagery can limit communication, except in the case of certain universal dreams. Given that, it should be only a matter of time before someone paints my own favorite, “Showing up for the final exam when you haven’t attended a single class.”

The Equitable Gallery

1999